Cronobacter sakazakii: Pathogen Considerations beyond Salmonella in Dairy Powders

Low-moisture foods present challenges for pathogen control

By Dave Cook

> LOW MOISTURE

Photo credit: ddukang/iStock / Getty Images Plus via Getty Images

SCROLL DOWN

Cronobacter sakazakii is an ubiquitous, opportunistic pathogen that is drawing interest from dairy powder customers, regulators, and industry. If you are in the dry dairy arena, this organism is or will become important to you. In this article, we review the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s findings on prevalence of Cronobacter spp. in dry dairy plants, Cronobacter’s significance, and industry best practices for monitoring and control. We will also share a practical approach to beginning a C. sakazakii (C. sak) program in your facility.

First, a little about C. sak. It is a Gram-negative rod in the Enterobacteriaceae (EB) family and has caused illness and death in infants. Infants and immunocompromised, tube-fed elderly people are particularly susceptible, and mortality rates can exceed 40 percent in these vulnerable populations. Cronobacter, like Salmonella, survives well in dry environments and in low aw foods like dairy powders. Cronobacter is a vegetative organism that is readily destroyed by pasteurization, so contamination events primarily occur through recontamination of powder in drying, storage, handling, and filling areas. Note: This does not negate the need for strong controls on the liquid side of your process. Your finished product quality and safety rely on presenting clean product to your dryer. The drying process does not improve quality or cover mistakes made earlier in the process.

Cronobacter is not identified in fecal coliform or other coliform tests, but it is recovered in the broader EB tests that many dairies use. EB is a more inclusive indicator test, and you will find EB more often than coliforms, Cronobacter, or Salmonella. This makes the EB test a valuable tool in detecting and preventing outgrowth of Cronobacter populations. Best-in-class programs probably include both coliform and EB testing in finished products to ensure a broad-scope approach to identifying postprocessing contamination risks. Additionally, monitoring and controlling EB in the environment is a key enabler to control both Cronobacter and Salmonella.

The Prevalence of C. sak in Dry Processing Facilities

FDA conducted a sampling assignment in 2014 to understand the prevalence of Cronobacter spp. and Salmonella in 55 U.S. dry dairy facilities.¹ If you have not seen this report, I suggest reading it completely as we share only some highlights here. Cronobacter was detected in 69 percent of the facilities, with an average of 4.4 percent positives overall and 6.25 percent positives in the 38 plants that had positive findings. As would be expected, the highest Cronobacter rates were found in zone 4 (14.3%). Positive rates decreased progressively, with 8.7 percent in zone 3, 4.5 percent in zone 2, and the fewest positives found in zone 1 (1.1% in product contact sites).

By contrast, Salmonella was found in only three (5.5%) of the 55 facilities sampled. Salmonella was found in 0.16 percent of all samples and 2.5 percent in the three facilities that had positives. In the facilities that had positives, we see a similar trend, with the zone 4 samples having the highest positive rate. The rate decreased in zone 3 samples, and no Salmonella positives were found in zone 2 or zone 1 samples.

The data comparison between Salmonella and Cronobacter is an indicator that the hygienic zoning control that industry uses against Salmonella is already working to minimize Cronobacter. However, a positive rate of over 1 percent in zone 1 sites indicates other strategies are needed to reduce the Cronobacter risk further. If you take into consideration that Cronobacter is more ubiquitous than Salmonella with a higher frequency of occurrence in the environment, we should logically conclude we need more, different, or enhanced barriers to keep the organism out of our high-hygiene zone 2 and zone 1 areas.

There are some wonderful publications on how to reduce Salmonella and Cronobacter populations in plant environments. Two that should be in your library are the Consumer Brands Association’s timeless guidance found in Control of Salmonella in Low Moisture Foods and Enterobacter sakazakii and Salmonella in Powdered Infant Formula: Meeting Report from the World Health Organization, specifically chapter 4.

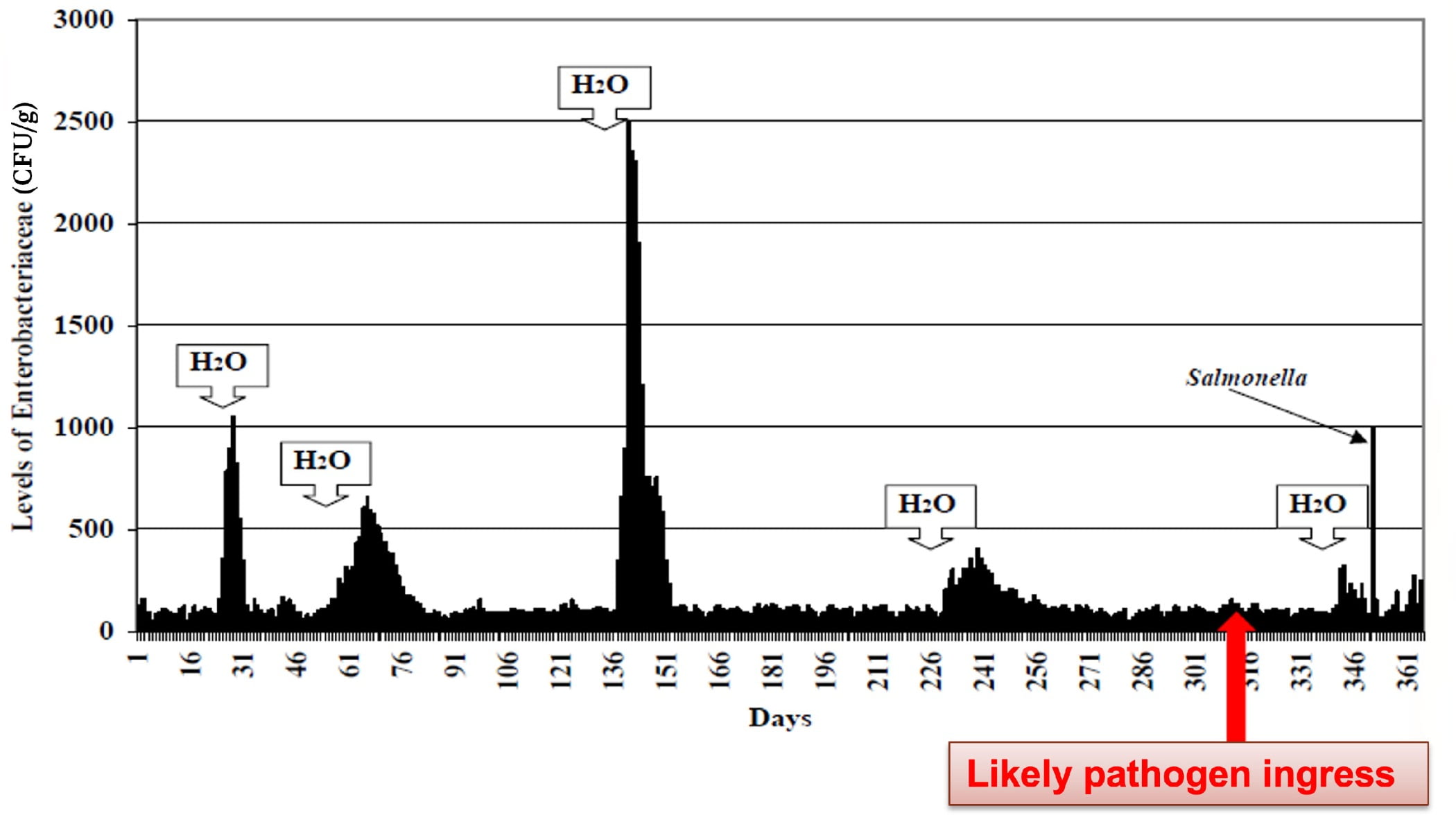

The basic controls referenced in these documents will help you i) with optimal facility and equipment design, ii) keep the undesirable organisms out of your facility, iii) maintain zones of controls and barriers to act as hurdles for organisms trying to enter your finished-product areas, and iv) keep the facility clean and dry. Dry is especially important. Think of these organisms like seeds in the desert. They grow only when moisture is added. If you have a dry plant, keep it dry. This principle is displayed well in Figure 1, which shows how moisture addition to the environment creates dramatic increases in EB findings. In this case, the likely ingress of Salmonella into the environment is indicated, whereby, when water was added, the Salmonella grew and became detectable. Whether it is the indicator EB, the opportunistic pathogen Cronobacter, or Salmonella, all of these organisms grow exponentially where water is introduced.

These principles and others are also presented in the Dry Dairy Plant Food Safety workshops offered by the Innovation Center for U.S. Dairy. These workshops are an excellent way for you to meet peers dealing with the same issues and learn from subject-matter experts working in this area daily.

Chad Galer, vice president of food safety and product research at the Innovation Center for U.S. Dairy, shared that “the Innovation Center’s Food Safety Committee offers several relevant resources and has organized action teams around dry dairy food safety best practices. The Innovation Center offers one to two workshops focused on dairy plant food safety for dry dairy operations each year. They have also organized the industry to develop a guidance document titled Controlling Pathogens in Dairy Processing Environments that has relevant and specific information for dry dairy pathogen control. Topics covered in the guidance document range from sanitation and environmental monitoring to specific considerations for managing system breaches.” All these resources and more can be found at usdairy.com/foodsafety or by emailing Chad

.

This may seem like a lot of discussion and resources before getting to the how-to on Cronobacter control. This is intentional, because you need to know where you are and what you may find before starting a new pathogen control program. It is advised that you seek guidance and approval from appropriate company resources before beginning.

FIGURE 1. Postmortem of a Salmonella Incident

The Control of C. sak in Dry Processing Facilities

Some thoughts before you begin. Be prepared for this to take time, probably months or even years. The process requires risk assessment, testing, and consistent implementation of control strategies before you can safely reach a steady state of C. sak control.

Some Reasons You May Want to Start a C. sak Program

- You want to pursue new customers or export markets with your dried powders, and you see certain export markets have C. sak on their expectations.

- You want to start selling your powders into the infant formula market, and they have C. sak specs.

- You were one of the facilities that participated in the FDA C. sak sampling exercise, saw the results, and want to gain better understanding of risk and occurrence of this organism in your plant.

- You had a recent complaint of elevated EB in your product from a customer. Their investigation included speciation of the organism, they found C. sak, and they have rejected your product as adulterated.

- You want to get ahead of any potential regulatory changes that would require these controls.

>> SIDEBAR

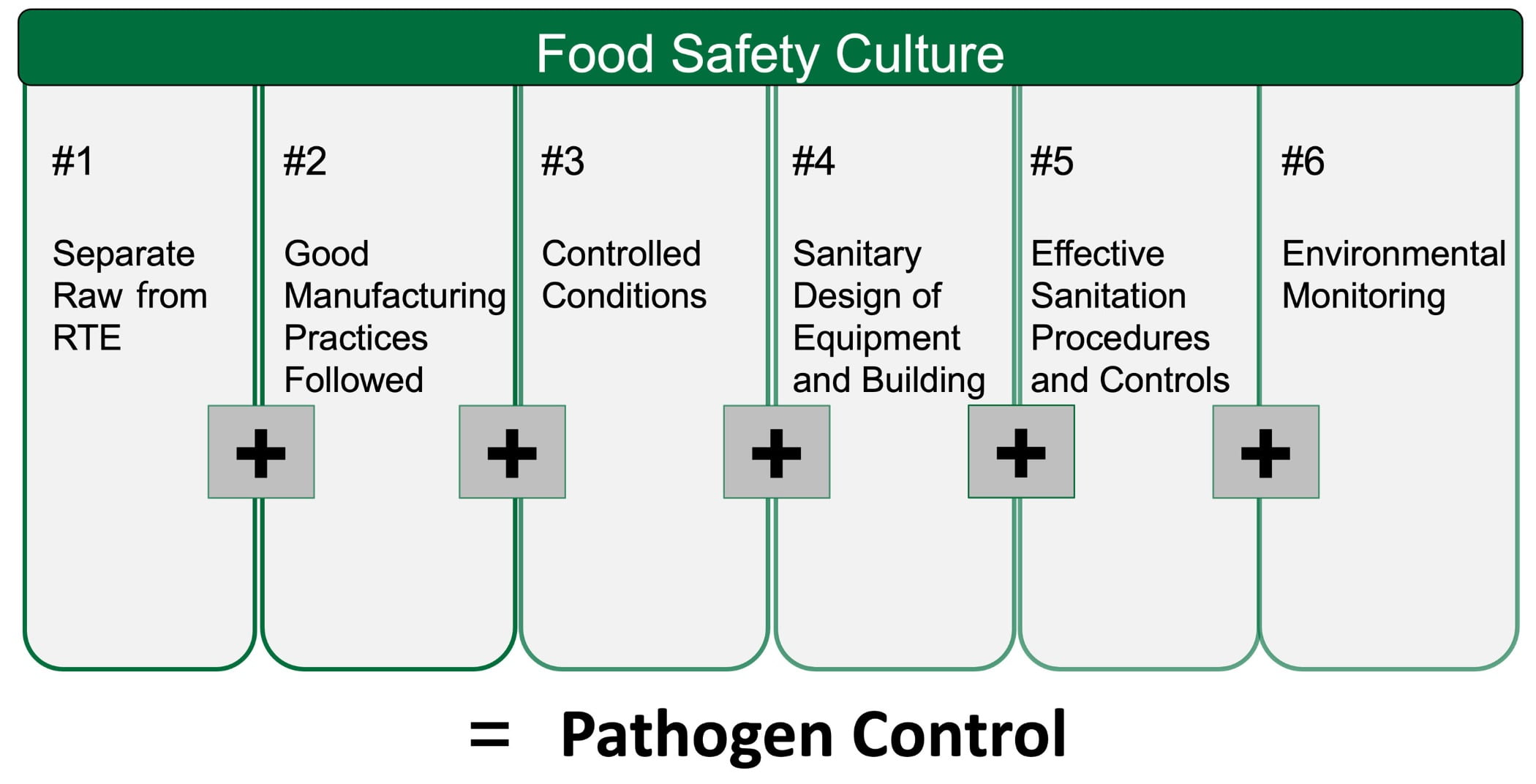

Start by evaluating your current control programs. Consider auditing yourself against the pathogen “equation” shown in Figure 2. There is a helpful checklist that outlines minimum expectations and industry best practices for the pathogen equation available at Dairy Pathogen Control Program Assessment.

If you have items 1–5 of the pathogen equation in good order, evaluate your environmental monitoring program (EMP), which helps you verify that your controls are working. Make sure your current program and results are solid before expanding into C. sak monitoring.

Ask these questions about your current EMP:

- Do you have Salmonella swab programs well established?

- Do you have a zoning map, and do you know why all your current sites were selected?

- Do you know the implications and actions you would take for each of your sites if it were to be positive?

- Does your swab program match the risks identified in your facility?

- Do you cover areas where product and/or moisture could build up?

- Do you allow random swabs to be taken based on observations during operations and routine swabbing?

- Do you have protocols for swabbing around water events like roof, ceiling, equipment, or drain leaks?

If you have these areas covered, and results are in control, next consider your EB monitoring program, which includes the following:

- Do you swab for EB as an indicator of sanitation and moisture control? If you do, how do the EB results tie back into your Salmonella sites and control strategy?

- Do you know why each of the sample sites was chosen and what elevated counts mean for your facility? What are your corrective actions if you get elevated counts?

- Are those corrective and preventive actions (CAPAs) effective?

- What is your EB threshold?

- Do you connect both EB and Salmonella hits to increased product testing?

- What is the water control strategy in your facility?

- If water is still used, do you track how that water use impacts your environmental results?

If you do not have clear answers to these and similar questions, you will need to do preliminary baseline work before moving into a C. sak evaluation program.

FIGURE 2. The Pathogen Control “Equation”: A Food Safety/Quality Principles Approach

The following baseline work to prepare for a C. sak program will aid in your success and minimize the risk of unforeseen consequences coming from your new program. Essentially, you want to be sure that your programs to control EB and Salmonella are well established and effective. If you are controlling EB, you have a high likelihood of controlling C. sak. Here are some recommendations:

Review and update your risk assessment of the Salmonella sites selected. Take into consideration the pathogen equation discussed earlier, transition zones, and water use when conducting the risk assessment.

Review your EB sites; make sure they are connected to the reasoning for Salmonella sites.

Prepare to do an EB swab-a-thon (probably 100 or more EB swabs) of your facility focusing on zones 1–4. This will be your baseline assessment of possible areas to focus on for improved control.

- When taking the EB swabs, use the collection tool suitable for the location and ensure counts are standardized to a surface area if the sample sites are not uniform in size.

- Review the collected data to determine what they indicate about the maturity of your EMP, water control, and initial risk assessment.

- Expect elevated counts in any areas that have water.

- Expect elevated counts in zones 4 and 3, lower counts in zone 2, and low counts in zone 1.

- Does the trend from lower-control to high-control areas make sense? Are your hygiene controls working as designed to keep risk out of exposed product areas such as your packaging room?

- Do you have any other exposed product areas, such as a dry rework hopper or sifter tailing containers with elevated counts?

- Conduct a CAPA on the sites with elevated counts, focusing on zones 2 and 1 as well as exposed product zones.

- Implement control strategies and take verification swabs until you have confidence you have identified why counts might be elevated and how to ensure they remain low. This should include a clear connection to employee touch points/Good Manufacturing Practices (GMPs), water use, and traffic controls (along with other variables in the pathogen equation) so you have a full and robust picture of the risks to your EMP.

- If you have elevated counts in the environment, do you see elevated counts in product? If you do not know, now is the time to find out. Pull extra product samples for EB when you identify risk to product from elevated EMP EB counts.

At the end of this exercise, you should know exactly what your risks are for elevated EB counts and what impact that can have on your product.

“The data comparison between Salmonella and Cronobacter is an indicator that the hygienic zoning control that industry uses against Salmonella is already working to minimize Cronobacter.”

Assessing the Risk of C. sak

Once you feel the EMP for EB and Salmonella is well defined and controlled and you understand how that data impact your finished product, you can expand your evaluation of C. sak risk. Conduct an initial swabbing exercise for C. sak in your facility focusing on zones 2, 3, and 4. I suggest you avoid zone 1 (product contact sites) until you know that you have the surrounding zones in control.

If your baseline work and investigations were robust, your C. sak-positive sites should reflect what you learned in your EB investigations and risk assessments.

- If your C. sak results are higher in your zone 2 exposed product areas than you expected, revisit your EB program, water control, and pathogen equation risks.

Note: When testing directly for C. sak, it is common to use a rapid method for screening. Some polymerase chain reaction-based methods may have a high presumptive positive rate, so be prepared to confirm the presumptive results. Partner with a reliable contract lab that can help you interpret the results and conduct confirmations quickly to keep your testing progress on track. You may find as many as 50 percent of your rapid-test presumptive positives do not confirm to be C. sak.

- It is not uncommon to see a significantly higher C. sak-positive rate in your environment than what you see for Salmonella; C. sak is more prevalent in the environment than Salmonella. Expect to see higher counts in your zone 4 and maybe even zone 3 sites, depending on water control strategies, hygienic barriers, and other factors.

- You should not see elevated counts in your higher-hygiene rooms. It is critical that your personnel GMP controls for hygiene junctions and controls for exposed-product rooms are well managed and understood before you proceed with any product testing for C. sak.

- Evaluate whether any of the C. sak environmental testing sites are critical to your understanding of your risk. It is possible to have a robust C. sak EMP that does not include routine C. sak swabbing. EB may be the better indicator of risk, and it is less expensive, faster, and can usually be conducted in-house.

You have conducted the risk assessments and tested for and controlled EB in your product and environment. You are under control and can now consider testing product and/or zone 1 sites for C. sak. Here are some further considerations and hints to guide success while minimizing risk:

- Before you start C. sak testing of product or zone 1, ensure you have a clear picture of the coliform and EB counts in your product. If you have routine low-level coliform or EB in your product, it is likely you will find C. sak in your powder and you should eliminate the low-level EB in product before C. sak testing.

- Conduct a full risk assessment on your product portfolio to include customer specifications, uses, and consumer base. Expect to have some finished lots/zone 1 sites test positive for C. sak.

- It is recommended to focus on those products that will go into further processing with a validated kill step. C. sak is a pathogen of concern for infant formula (dry blend in particular) and products that go to certain high-risk consumers. If your customer has a validated kill step in their application or does not sell to those high-risk markets, your risk assessment may or may not indicate it is safe and acceptable to sell a C. sak-positive lot to those customers. Again, these are decisions to have vetted at the appropriate level within your organization before any testing begins. Always know what you will do with an adverse result before you do the test.

- Define your approach to testing, how many lots you want to test, what production process variations you want to represent in zone 1 testing, and what you will do with any positive results.

- If you are testing finished lots, it is suggested to pull dryer-feed liquid samples of that same product for evaluation.

- If you find zone 1 or product positives, do a full CAPA and identify whether you have an environmental risk you missed in your initial assessment and address before further C. sak testing. Revert to EB testing and control strategies.

- If the liquid is also positive, halt further powder testing and focus attention on your liquid processing. Investigations for C. sak will be similar to coliform or EB investigations.

Do you know why you see C. sak positives in product or zone 1? If you do not, you should circle back through the assessment program until your risk profile and control strategies are clear to all members of your team so you can work together to ensure safe product.

What is your positive rate? Most dairy producers entering a C. sak-testing program will need to accept some level of positive lots and have a clear strategy to ensure they control that risk for their customers.

“Once you have a program and have determined you can accept customer specs for C. sak on some production lines, continue your strategies for improvement.”

Testing Finished Product for C. sak

If you choose to accept C. sak specs for your customers, you should expect to have a requirement to test each finished lot for C. sak. This will be critical to monitor your positive rate and ensure control; this is done in tandem with your EB and Salmonella programs. The following steps will help you develop and implement such a testing program:

- Define your strategy to investigate and evaluate any C. sak positives. Conduct further testing within the lot to determine a root cause, or use EB or another indicator testing as appropriate. CAPAs should include EMP review and may include enhanced sanitation and investigative swabbing.

- Determine your strategy for lot selection for those customers with a C. sak spec. Even if their specification does not indicate it, you should select only those lots with low-level aerobic plate counts, no history of in-process or finished-product coliform/EB, and no processing deviations that would elevate risk.

- C. sak-negative lots for a customer spec should be bracketed by other C. sak-negative lots. In a continuous manufacturing process, your data should indicate strict process/micro control to ensure the highest confidence in your negative result.

- As with any specification, once you accept a C. sak spec and test/release against it, be prepared for an occasional customer rejection for C. sak.

- Not all customers will be as educated as you have become about the testing challenges; verify they have confirmed the result.

- They may insist on destroying product as adulterated; if you disagree and risk assessment supports it, you may be able to accept a return of the product and find alternative safe uses for this lot.

Looking Ahead: Continuing Your Improvements

Once you have a program and have determined you can accept customer specs for C. sak on some production lines, continue your strategies for improvement. This will further lower your risk and allow you to pursue more customers/specs/markets.

- Continue to press for lower EB in the environment: Instead of thresholds of less than 100 or less than 10, move to negative EB in your high-hygiene areas.

- Continue to challenge your finished product for EB; can you achieve a negative EB in all your finished lots?

We hope this article has given you information about an emerging, opportunistic pathogen, some resources and tools to understand and mitigate its risk, and a framework to safely implement a control program that provides C. sak-free products to markets and consumers that need it. You should take away two things from this article:

- If you control hygienic zones, provide hurdles to entry, and keep your facility dry, this will reduce your environmental load and associated risk.

- If you monitor and control EB, you are well on your way to success.

Reference

- Hayman, M.M., et al. 2020. “Prevalence of Cronobacter spp. and Salmonella in Milk Powder Manufacturing Facilities in the United States.” J Food Prot 83(10): 1685–1692.

Dave Cook is the president of Commercial Quality and Food Safety Solutions.