PROCESS CONTROL

By Tim Lombardo, Senior Director, Food Consulting Services, EAS Consulting Group

Fundamentals of Conducting an Allergen Gap Assessment

Conducting an allergen gap assessment is one way to ensure regulatory compliance and consumer safety

Image credit: onurdongel/E+ via Getty Images

SCROLL DOWN

The issue of allergen-related food recalls is arguably of greatest concern and least understood in the food industry. Since the enactment of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's (FDA's) Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) in 2011, increasing numbers of allergen-related food recalls are seen, indicating that the industry is still struggling with designing and implementing effective allergen controls.

The vast majority of issues with undeclared allergens in food are unintentional. Undeclared allergens continue to be responsible for the highest percentage of reported FDA food recalls, entering the food supply through:

- Breakdowns in processing, labeling, and storage

- Communication gaps between suppliers, co-packers, and manufacturers.

Conduction an allergen gap assessment in your facility could aid in mitigating these breakdowns and communication issues.

What is a Food Allergy?

Before conducting an allergen gap assessment, we must first take a step back to better understand what having a food allergen means. A food allergen is a food or component(s) of a food (often a protein) that elicits specific immunologic reactions. Food allergy is a form of food hypersensitivity, which can be broadly defined as an adverse health effect arising from a specific immune response that occurs with the exposure to a given food. These reactions are categorized as either food allergic reactions (immune mechanisms) or food intolerances (non-immune mechanisms).

Food Allergic Reactions

A food allergy occurs when exposure to a particular food triggers an abnormal immune response. Immunoglobulin E (IgE) is made in the human body after exposure to a substance the immune system recognizes as foreign and potentially harmful. For most people, this is an automatic response to fight off parasites. However, for people with food allergens, IgE is generated in response to the consumption of the food allergen. The IgE process begins in lymphoid tissues such as the tonsils, adenoids, and bone marrow, and then diffuses through the tissues and into the bloodstream.1

Allergic reactions can happen fast, within minutes of consumption or exposure, or they can take up to several hours to appear. Food allergies recognized as the most severe and immediately life-threatening are those mediated by IgE antibodies. These types of food allergic symptoms are unpredictable and can involve a single organ system:

- Skin: erythema, angioedema, eczema

- Eyes: conjunctivitis, swelling

- Nose: sneezing

- Oral cavity: swelling and itching of lips or tongue

- Gastrointestinal tract: reflux, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea.2

The most severe IgE-mediated food allergic reactions involve the "shock organs" of the respiratory tract or cardiovascular system, involving signs such as cough, wheezing, difficulty breathing, swelling of the larynx or vocal cords, fainting, and low blood pressure. These anaphylactic reactions can lead to loss of consciousness, asphyxiation, shock, or death.

For food allergic reactions that are not IgE-mediated, there is no association with anaphylaxis or other immediately life-threatening conditions. These reactions include celiac disease and contact dermatitis.

Food Intolerances

Adverse reactions that are not immune mediated can be caused by several factors, such as metabolic mechanisms (lactose intolerance), pharmacologic mechanisms (reaction to caffeine), toxicological mechanisms (scombroid toxin poisoning), or other undefined mechanisms (reactions to sulfites). In the U.S., these reactions are not considered the same as food allergic reactions, but instead are classified as food intolerances.

Landmark FDA Regulations

Within the past dozen years, two major changes to food safety have been enacted: FSMA in 2011 and the Food Allergy Safety, Treatment, Education, and Research Act (FASTER Act) in 2021.

FSMA was the most sweeping reform of U.S. food safety laws in more than 70 years. To date, FDA has finalized nine rules and programs to implement FSMA, each designed to make specific actions that must be taken at different points in the global supply chain for both human and animal food to prevent contamination. These rules and programs include:

- Standards for the Growing, Harvesting, Packing, and Holding of Produce for Human Consumption (also known as the Produce Safety Rule) (21 CFR 112)

- Current Good Manufacturing Practice, Hazard Analysis, and Risk-Based Preventive Controls for Human Food (21 CFR 117)

- Final Rule for Mitigation Strategies to Protect Food Against Intentional Adulteration (21 CFR 121)

- Current Good Manufacturing Practice, Hazard Analysis, and Risk-Based Preventive Controls for Food for Animals (21 CFR 507)

- Foreign Supplier Verification Program (21 CFR 1, Subpart L)

- Accredited Third-Party Certification Program (21 CFR 1, Subpart M)

- Final Rule on Sanitary Transportation of Human and Animal Food (21 CFR 1, Subpart O)

- Laboratory Accreditation for Analyses of Foods Program (21 CFR 1, Subpart R)

- Final Rule on Requirements for Additional Traceability Records for Certain Foods (21 CFR 1, Subpart S).

FSMA, and specifically 21 CFR 117, requires that both domestic and foreign food facilities conduct a hazard analysis for foreseeable food safety risks, including the introduction of allergens, and to implement a system of risk-based preventive controls for those identified hazards. Known as Hazard Analysis and Risk-Based Preventative Controls (HARPC), an allergen control program is included as part of this hazard assessment and preventive strategy.

Later, in 2021, the FASTER Act was signed into law, declaring sesame as the ninth major food allergen recognized by the U.S. Other major U.S. food allergens include milk, eggs, fish, crustacean shellfish, tree nuts, peanuts, wheat, and soybeans (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. The Nine Major Food Allergens for the U.S. (Source: U.S. FDA)

TABLE 1. FDA Recalls in Review3

TABLE 2. USDA Recalls in Review4

On average, for 2021–2023, allergen-related recalls for FDA-regulated foods accounted for more than half of all food recalls. For the same period, pathogen and foreign material related recalls accounted for approximately 35 percent and 5 percent, respectively. Comparatively, for 2021–2023, allergen recalls for USDA-regulated foods accounted for nearly one quarter of all recalls, with pathogen and foreign material recalls accounting for approximately 36 percent and 4 percent, respectively.

Further FDA Involvement and Enforcement

In response to the consistently large numbers of food recalls associated with allergens over the years, reducing consumer exposure to food allergens and ensuring compliance to food regulations are a top priority for FDA. Indeed, within the past two years, FDA has published several food allergy-related documents.

- Draft Guidance for FDA Staff and Stakeholders: Evaluating the Public Health Importance of Food Allergens Other Than the Major Food Allergens Listed in the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (April 2022)

- Guidance for Industry: Questions and Answers Regarding Food Allergen Labeling, Edition 5 (November 2022)

- FDA Letter to Industry: Food Safety Risks of Transferring Genes for Proteins that are Food Allergens to New Plant Varieties Used for Food (April 2023)

- Compliance Policy Guide (CPG) Sec 555.250 Draft: Major Food Allergen Labeling and Cross-Contact (May 2023)

- Draft Guidance for Industry: Hazard Analysis and Risk-Based Preventive Controls for Human Food (Chapter 11: Food Allergen Program ) (September 2023).

To reinforce compliance, FDA enforcement of allergen controls is detailed in several sections of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (21 USC 343):

- Allergen labeling. The article is misbranded in that the label fails to declare all major food allergens present in the product.

- Ingredient declaration. The article is misbranded in that it is fabricated from two or more ingredients, and its label fails to bear the common or usual name of each such ingredient.

- False or misleading. The article is misbranded in that the labeling is false or misleading.

- Manufacturing conditions. The article is adulterated in that it has been prepared, packed, and held under insanitary conditions whereby it may have been rendered injurious to health.

FDA enforcement in any one of these areas can result in product recall, a warning letter (FDA 483), as well as product detention, seizure, and suspension of registration. In extreme cases, if FDA determines continued noncompliance, then the Department of Justice can file a complaint against the company and facility followed by a consent decree of permanent injunction. The consent decree will include detailed criteria that a firm must meet to reopen and continue operations.

If a food or food ingredient is imported into the U.S., then the food can be detained at the port for allergen misbranding or adulteration under an Import Alert, and the company can even be debarred from food importation.

“Allergen control is not like pathogen control, because the hazard cannot be removed at a critical control point once an allergen (declared or undeclared) is in the supply chain.”

Conducting an Allergen Gap Assessment

From a food manufacturing perspective, sorting through all of the regulations and guidance documents, as well as FDA enforcement trends, can be overwhelming. To complicate things further, system failures can occur at every link in the chain. To fully understand what works and what does not, the best way to start is by conducting an allergen gap assessment.

Preparation

The first step in conducting an allergen gap assessment is to identify all applicable reference materials. Some of these references are required for minimum regulatory compliance, such as:

- Current Good Manufacturing Practices, Hazard Analysis, and Risk Based Preventive Controls for Human Food (21 CFR 117)

- Draft Guidance for Industry: Hazard Analysis and Risk-Based Preventive Controls for Human Food (Chapter 11: Food Allergen Program)

- Compliance Policy Guide (CPG) Sec 555.250 Draft: Major Food Allergen Labeling and Cross-Contact.

Additional references may be used, such as a facility's third-party audit standard, as well as other regulatory body reference materials.

Once all of the applicable standards have been determined, a checklist should be developed to capture each requirement. Then, using the facility's food safety plan process flow diagram, all applicable allergen requirements should be listed for each step (Table 3).

TABLE 3. Examples of Allergen Gap Assessment Checklist

Conduct the Assessment

Allergen control is not like pathogen control, because the hazard cannot be removed at a critical control point once an allergen (declared or undeclared) is in the supply chain. When conducting the allergen gap assessment, it is important to include all processing steps, the associated procedures, employee training requirements, as well as recordkeeping. Focus on the potential of allergen "movement" from step to step.

Include a review of the ingredient procurement process that encompasses all ingredients and sub-ingredients, as well as all suppliers. Take note of any food allergens that are not included in the ingredient list but may be present in the supplier's facility. If the facility has an onsite research and development (R&D) lab, review all R&D ingredients that may be present in the facility but not used in standard production.

Review each processing step, from ingredient receipt through finished product storage. Assess how ingredients are brought to the floor, weighed, mixed, and returned to the warehouse. Assess airflow and dust collection throughout the facility. Review traffic flow at each processing step, including:

- Production employees, as well as transient employees (quality control, maintenance, warehouse, and management)

- Ingredients

- Work-in-progress or finished product

- Trash removal.

If a preventive control is required at a specific processing step, verify the activities as required in the Food Safety Plan.

Assess Good Manufacturing Practices (GMPs) at each processing step. Verify the use of color-coded utensils, if any. Review proper handwashing, uniform exchanges, and traffic patterns.

Include a review of all cleaning procedures, cleaning chemicals, chemical concentrations, and verification activities, such as visual inspections and swabbing. Review equipment disassembly and maintenance equipment teardowns.

Review allergen swab sample site lists, as well as justification for the number of swab samples and frequency of testing. Review any verification and validation data, action limits, and corrective action plans if the limits are exceeded. Also include a review of the facility's corrective action/preventive action plan system.

Document the Gaps

Using the allergen gap assessment checklist, document all observations and findings for each section. Then, based on the appropriate standard, identify the gaps for each section (Table 4). Note that the same observation may be present at multiple processing steps. These may later be combined, as applicable, in the corrective action plan.

TABLE 4. Examples of Allergen Gap Assessment Observations and Gaps

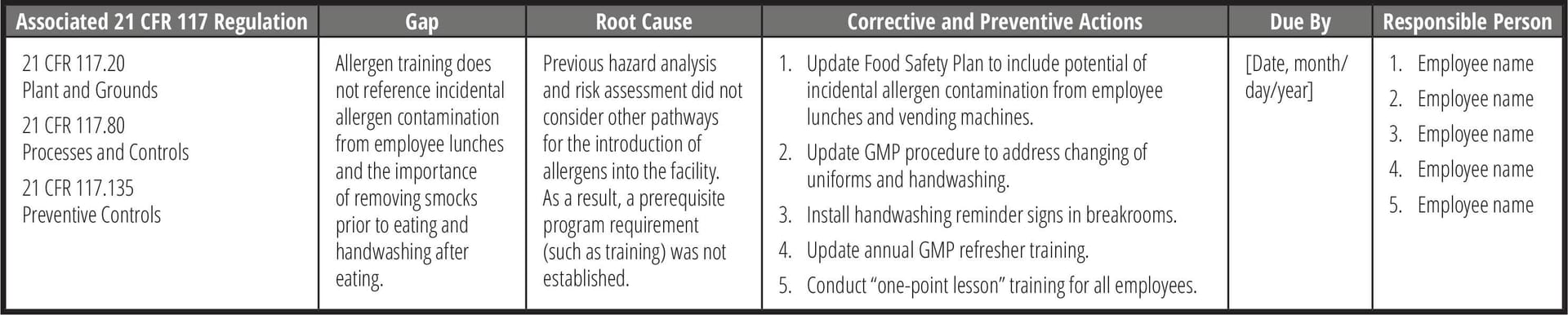

Address the Gaps

Once the gaps have been identified, the root cause of the gap must be determined to have an effective corrective and preventive action plan, or CAPA (Table 5). One of the more common techniques in performing a root cause analysis is the "Five Whys" approach, where the goal is to determine the root cause by repeating the question "Why?" five times. The answer to the fifth why should reveal the root cause of the problem. Another common technique is creating a Fishbone (or Ishikawa) diagram to visually map cause and effect. This can help identify possible causes for a problem by following categorical branched paths to potential causes until arriving at the right one.

TABLE 5. Example of Root Cause and Corrective Action Tracking

In addressing the gaps, CAPA plans should take the following into account:

- Processing controls. Include procedures like process scheduling, traffic control, physical segregation, and air filtration to prevent allergen cross-contact. Design facilities and equipment to minimize allergen cross-contact, use dedicated tools and apparel, and control material movement and airflow.

- Education and training. Ensure staff are trained in identifying allergens, principles of cross-contact prevention, and specific protocols for prevention, including corrective actions.

- Receiving and storage controls. Verify labels and ingredients upon receipt, handle damaged packages carefully, and use clear identification for allergen content. Implement segregation and distinct markings for allergen-containing materials. Store rework and work-in-progress (WIP) in labeled containers, establish tracking systems, and ensure allergen information is attached to each container.

- Production scheduling. Schedule production runs to separate allergen-containing and non-allergen products and consider clustering allergen-containing runs.

- Rigorous supplier audits. Conduct thorough assessments of new suppliers' allergen control procedures. Ensure there is a review process for supplier's internal and third-party audits. Evaluate detailed ingredient specifications.

Verification Reviews

Taking CAPA plans through effectiveness checks not only validates that the solution did work, but it also helps to minimize the risk of reoccurrence. Further, verifying the effectiveness of a CAPA closes the loop between identifying a problem and completing the actions to solve a problem. There are many highly effective tools and principles you can use to make your effectiveness checks successful. Here are a few common approaches:

- Trend analysis. In cases of human error, training, cleaning issues, and testing errors, trend analysis can help you determine if the corrective action has remediated the issue. Review data over a specific timeframe and determine if the problem or deviation has occurred again (or as frequently) after the corrective action was implemented.

- Periodic checks. This method involves scheduling a time for the quality unit to review the process that was remediated. For example, if there was a CAPA implemented to improve gowning practices in/out of an allergen room, the auditor can observe the newly improved gowning practices prior to the operator entering the cleanroom.

- Surprise audit. Audits are intended to ensure that the operators, process, or equipment follow the prescribed corrective action documented in the CAPA.

- Sampling. Sampling and testing are effective in verifying corrective actions pertaining to environmental monitoring or lab testing. Most commonly, sampling is conducted at allergen changeovers when more than one product is produced on the same production line, and the results are used to verify efficiency of cleaning.

While some root causes may require a simple procedure update, retraining of staff, or recalibration of a piece of equipment, in many cases, CAPAs address more difficult issues. It is best practice to set up several effectiveness checks over a period and may possibly require numerous verification checks. All verification checks must be documented (Table 6).

TABLE 6. Example of CAPA Verification Tracking

Conclusion

Undeclared allergens continue to be responsible for a high percentage of reported food recalls, entering the food supply because of breakdowns in processing, labeling, and storage, as well as communication gaps between suppliers, co-packers, and manufacturers. This has resulted in incremental increases in food allergen recalls. Conducting an allergen gap assessment of your facility is one way to identify and address these breakdowns and communication gaps, therefore ensuring regulatory compliance and consumer safety.

References

- Yu, W., D.M.H. Freeland, and K.C. Nadeau. "Food allergy: immune mechanisms, diagnosis, and immunotherapy." Nature Reviews Immunology 16 (October 2016): 751–765. https://www.nature.com/articles/nri.2016.111.

- Patel, B.Y. and G.W. Volcheck. "Food Allergy: Common Causes, Diagnosis, and Treatment." Mayo Clinic Concise Review for Clinicians 90, no. 10 (October 2015) 1411–1419. https://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org/article/S0025-6196(15)00592-3/fulltext.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). "Recalls, Market Withdrawals, & Safety Alerts." https://www.fda.gov/safety/recalls-market-withdrawals-safety-alerts.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). "Recalls & Public Health Alerts." https://www.fsis.usda.gov/recalls?f%5B0%5D=year%3A445.

Tim Lombardo, Senior Director for Food Consulting Services for EAS Consulting Group, is a widely regarded expert in food safety and microbiology with over 30 years of experience leading these programs in manufacturing facilities.