PROCESS CONTROL

By John M. Wigglesworth Ph.D., REHS/RS, CPFS, PCQI, Seafood Safety Expert

Shrimp Processing: Safety, Quality, and Manufacturing of Cooked and Raw Frozen Products

Shrimp facilities must utilize their processing systems to reduce risks from external hazards and manufacture safety and quality into their products

Image credit: Hispanolistic/E+ via Getty Images

SCROLL DOWN

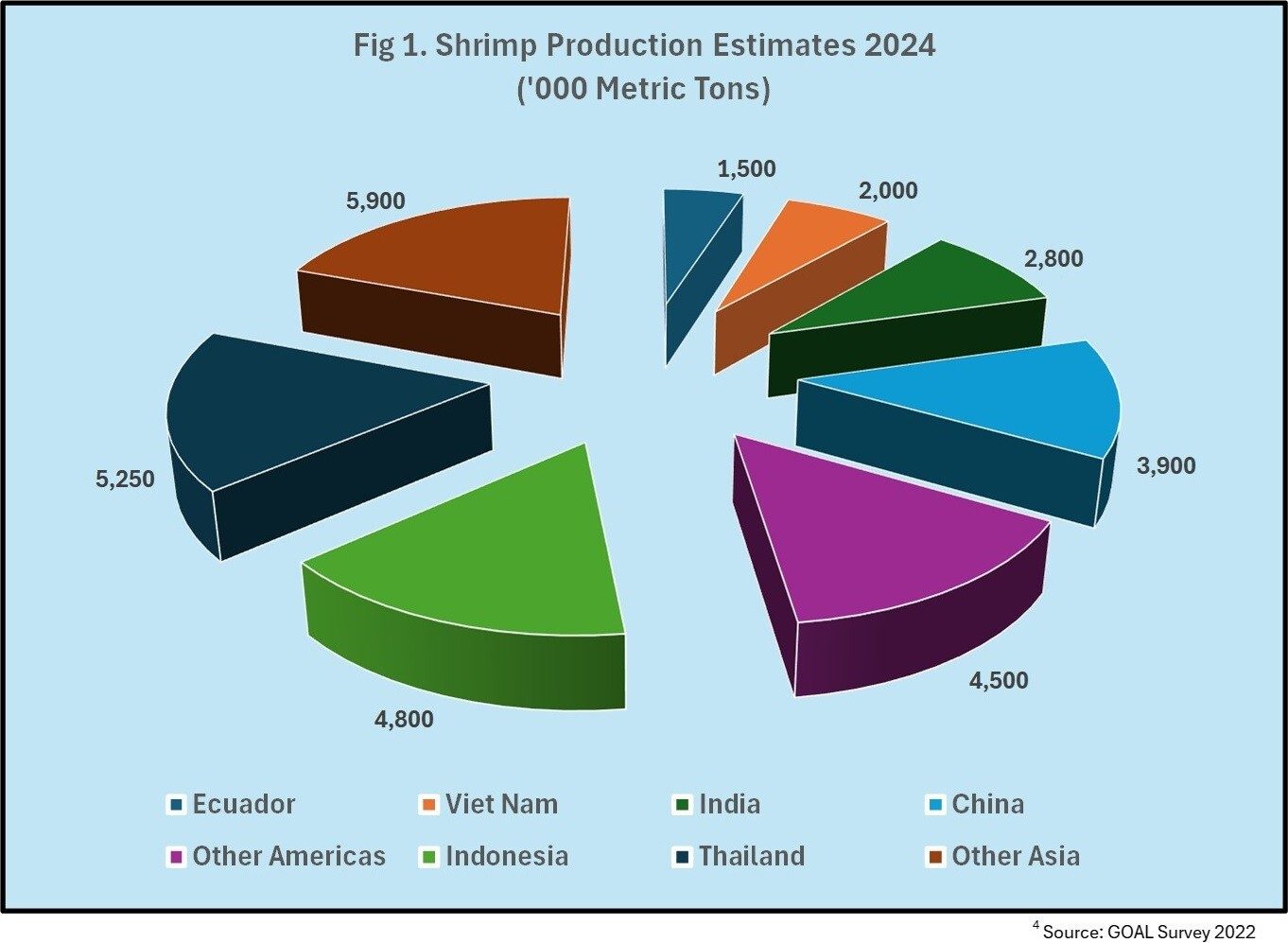

The global seafood sector is estimated to employ over 56 million people and contributes USD$200 billion to world trade.1 Within that sector, the global shrimp aquaculture market added 5.88 million metric tons (MMt) in 20242 and contributed USD$72 billion3 to that sector. The top five countries in production and processing are Ecuador (5.25 MMt), Indonesia (4.8 MMt), China (3.9 MMt), India (2.8 MMt), and Vietnam (2 MMt) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Shrimp Production Estimates, 20242 (Credit: J.M. Wigglesworth)

Aquaculture is the preferred method of production due to its inherent control, ability to capitalize on genetics programs, management of production cycles, and ability to satisfy global consumer preference for shrimp products. Once harvested, aquaculture product is processed in facilities that specialize in transforming shrimp into different forms, creating many raw and cooked products.

The process flow in Table 1 shows the main phases involved in shrimp processing, from raw material to finished frozen products, as well as associated safety, quality, preventive, and efficiency steps.

TABLE 1. Shrimp Processing Flow (Credit: J.M. Wigglesworth)

In 2022, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) identified the main problem facing the seafood industry as being food safety, with over 47 percent of seafood imports to the U.S. demonstrating contamination with banned chemotherapeutants and pathogenic bacteria. Essentially, the seafood sector, and shrimp aquaculture in particular, experience ongoing challenges in ensuring products are safe and of sufficient quality to support consumer confidence and public health.5

Except for a few highly controlled and isolated recirculating aquaculture systems, shrimp aquaculture occurs in outside ponds that are exposed to natural river, estuarine, and well water supplies, with little biosecurity to mitigate environmental contamination from biological and chemical sources. This does not necessarily mean that farms are in dangerous and contaminated watersheds; however, they are subject to external environmental risks in the same way the fresh produce industry is exposed to environmental risks. Consequently, this puts the responsibility on processing facilities to understand the external hazards and utilize their processing systems to reduce risks and manufacture safety and quality into the products they produce.

This article focuses on the fundamentals of shrimp processing and the various steps in which facilities can manage food safety and quality challenges to generate wholesome and safe products for global markets.

Raw Material Reception

Shrimp processing facilities receive raw material from four potential sources:

- First-party company-owned farms: These farms represent the source of raw material that offers greatest confidence. Good agricultural practices (GAPs) are generally applied, and the factory knows the source with confidence. Third-party certifications and transparency are usually employed in husbandry practices.

- Third-party contract farms: These farms have a long history of working with the factory, with established trust in the integrity of the raw material.

- Third-party spot purchase farms: These farms may be known or unknown, with very little knowledge of what inputs have gone into growing the raw material.

- Third-party consolidation centers: These facilities are where raw material is consolidated before delivery to the processing facility. The source farms are unknown, and there is little knowledge about the inputs used.

All four sources of raw material can be used, but only the first two sources offer assurances about provenance, husbandry, and input. Company-owned farms and third-party contract farms provide a basis for risk assessment regarding traceability, antibiotic use, and microbiological risk that third-party spot purchase farms and third-party consolidation centers do not. Knowledge of source allows the factory to complete pre-harvest sampling for safety, quality, and assessment of antibiotic risk and organoleptic parameters before raw material arrives at the processing facility.

“Pre-harvest and raw material sampling represent a testing point where one of the few safety checks can be completed during shrimp processing.”

After raw material is delivered to the factory, further samples are taken for antibiotic and sensory testing before the raw material is washed in chlorine solution (10 ppm) to reduce bacterial loads of coliforms, fecal coliforms, and pathogens such as Salmonella spp., Vibrio vulnificus, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, and Vibrio cholerae. Testing for banned antimicrobials such as chloramphenicol, nitrofurans, fluroquinolones, malachite green, sulfonamides, and tetracyclines can be performed in less than 2 hours (hr) using rapid test methods, such as Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA). Pathogen testing takes as long as 2–3 days using traditional methods but can be reduced to 24–48 hours using rapid detection methods. However, it is important to realize that these tests are only as good as the sampling protocols employed. Sampling protocols are extremely variable, since no statistically rigorous methods (such as the N60 sampling protocol for the detection of E. coli O157:H7 in ground beef) exist in shrimp sampling.

Raw material is also subject to sensory evaluation, which focuses on off-odors and off-flavors reminiscent of earthy or musty corn notes, generated by geosmin and other terpenoids produced by blue-green algae and actinobacteria. Off-odors and off-flavors result in the rejection of raw material since there is no effective remediation procedure.

Pre-harvest and raw material sampling represent a testing point where one of the few safety checks can be completed during shrimp processing. Screening for antibiotics can be achieved within 2 hours, allowing decisions to be made about chemical contamination. Although microbiological testing is also completed, it only represents a snapshot of the product at that moment, since microbiological profiles can and do alter during processing and following time spent in cold storage.6

Primary Processing Deheading and Grading

Following raw material acceptance, the material undergoes further washing with a 10-ppm chlorine solution to reduce bacterial load before being stored in ice at 3–4 °C. After this, the material undergoes deheading either manually or using automated deheading machines.

Since pond shrimp populations grow at slightly different rates, raw material at harvest has an average size with variability around that average. Table 2 shows how average tail weight of 10 grams (g) delivered to the factory has a weight range of 9.1–11.1 g due to the frequency distribution within the pond; however, this is not an issue since shrimp processing facilities have equipment designed to grade the product based on size.

TABLE 2. Weight Variability in Shrimp Processing (Credit: J.M. Wigglesworth)

The traditional method of grading consists of spinning parallel rollers that are positioned at an angle, adjusted to be narrow at the top and wider at the bottom (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. Machine Grading with Shrimp Introduced at the Top and Graded Down Spinning Rollers (Credit: J.M. Wigglesworth)

The shrimp are conveyed to the grading system and fall between the rollers at the appropriate width for that tail weight before being transferred to the next stage of processing.

Some facilities now employ the use of optical grading equipment that moves shrimp down a conveyor belt for optical evaluation. The shrimp are graded for weight, color, broken condition, defects, and foreign material at a rate of approximately 3,250 lb/hr, using ten grading lanes, vs. the roller grading machines that operate at rates of approximately 8,000 lb/hr, using seven grading lanes. Grading is important because it offers consistency in uniform sizing, establishment of accurate pricing for different sizes, efficiency in processing, and support of consumer expectations regarding size and appearance. Automated vs. manual grading affords greater speed and efficiency, reduction in waste products, reduced labor costs, and improved hygiene since it minimizes human contact.

Grading is also the main area that impacts profitability since the increase in shrimp pricing across sizes is not consistent. Bigger shrimp command higher prices, and even though grades of shrimp have count ranges, grading does not necessarily target mid-points for count. For example, 16–20 count will target 19–20, unless there has been a prior agreement to target a mid-point of 18. Grading is an extremely important part of shrimp processing and arguably the main area underpinning profitability in the factory, but it is also an area with few safety control points.

Secondary Processing and Material Streams

After grading is complete, the next stage involves peeling and cutting to remove sand veins or digestive tracts, further hand grading for large sizes above 13 count, and material streams to produce specific products. This step generates the starting material for all finished products that can be produced from one batch of raw material (Table 3).

TABLE 3. Raw Shrimp Product Forms in Secondary Processing (Credit: J.M. Wigglesworth)

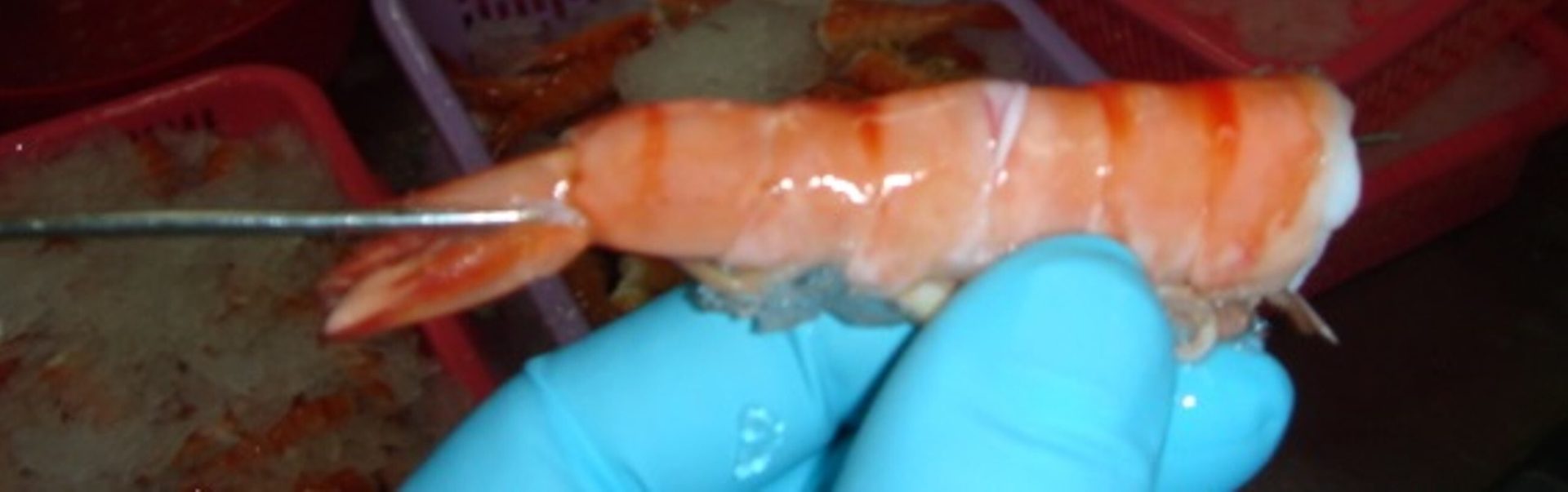

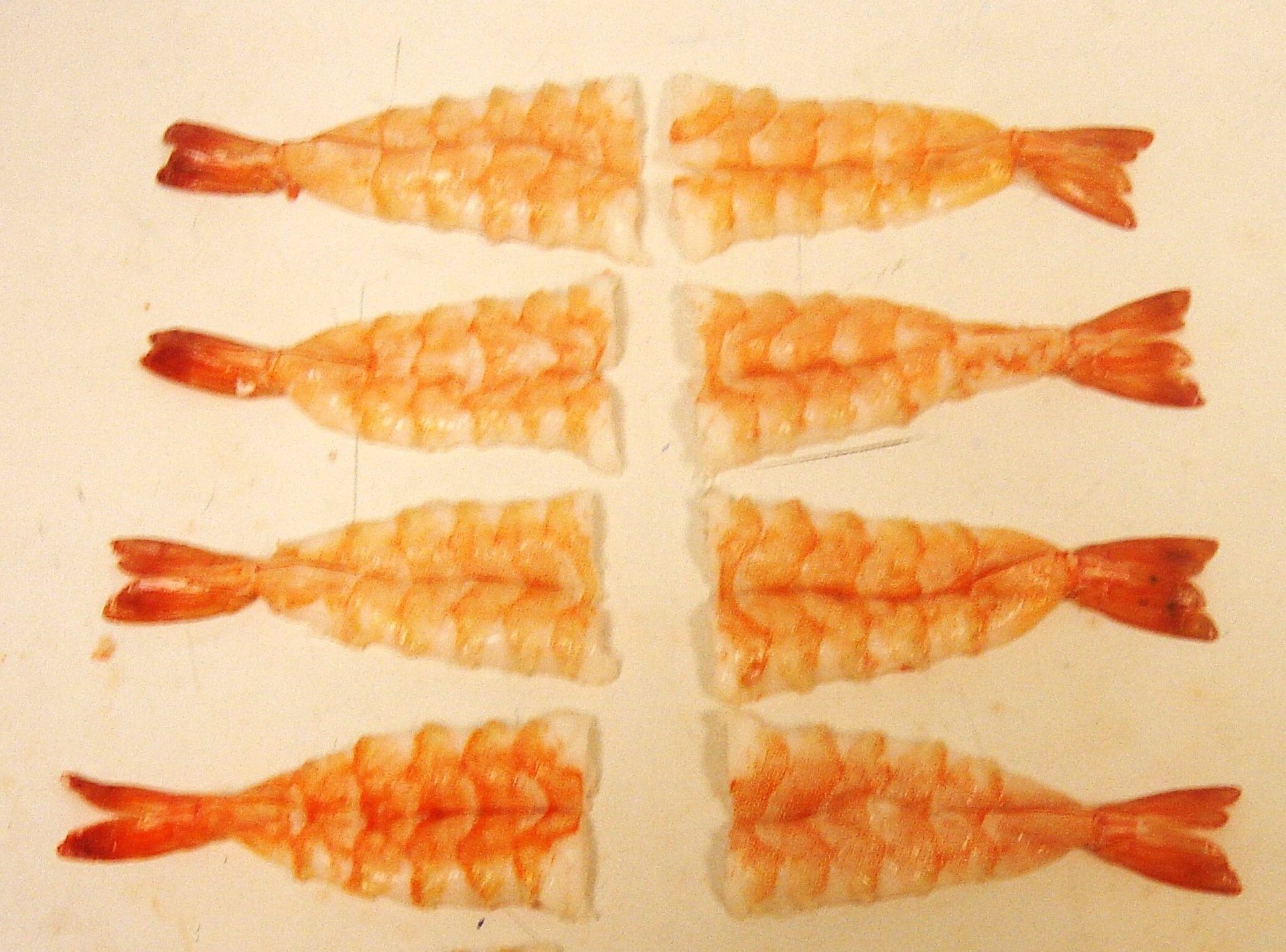

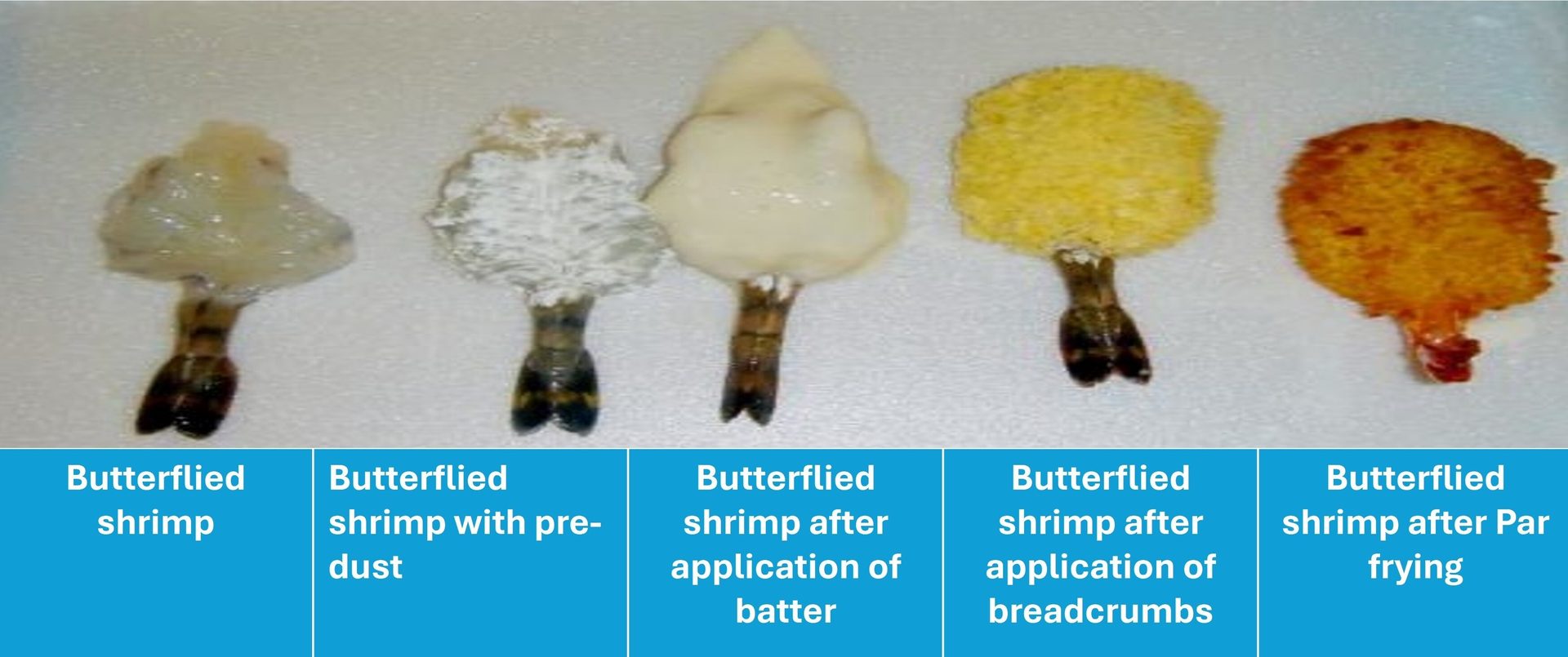

Shrimp processing is a segment of seafood manufacturing where many different product forms can be created from basic raw material. The first steps in secondary processing include removal of the sand vein that runs down the dorsal part of the shrimp (Figure 3), preparation of EZ-Peel product (Figure 4), peeling to create peeled, deveined, tail-on shrimp (Figure 5), preparation and trimming to create Sushi Ebi product (Figure 6 and Figure 7), and butterflying shrimp (Figure 8) prior to breading (Figure 9). While these are some of the main product types, shrimp processing is very versatile in creating other product forms.

FIGURE 3. Sand Vein Being Removed from the Tail (Credit: insjoy/iStock/Getty Images Plus via Getty Images)

FIGURE 4. Deep Cutting to Create EZ-Peel Shrimp, Sold as a Standalone Finished Product (Credit: J.M. Wigglesworth)

FIGURE 5. Peeled Deveined Tail on Shrimp, One of the Most Common Shrimp Forms (Credit: J.M. Wigglesworth)

FIGURE 6. Preparation of Sushi Ebi Shrimp with a Stainless-Steel Rod Inserted to Maintain Shape Before Cooking, Peeling and Trimming (Credit: J.M. Wigglesworth)

FIGURE 7. Finished Sushi Ebi Shrimp After Trimming (Credit: J.M. Wigglesworth)

FIGURE 8. Butterfly Shrimp Where the Product is Peeled and Deep Cut to Flatten the Shrimp Before it is Breaded (Credit: J.M. Wigglesworth)

FIGURE 9. Butterflied Shrimp Undergoing the Breading Process (Credit: J.M. Wigglesworth)

Soaking and Washing

This step involves soaking the partially processed shrimp in a solution containing sodium tripolyphosphate and sodium chloride, constantly stirring at 3–5 °C to increase water weight gain (Figure 10).

FIGURE 10. Shrimp Soaking in Sodium Tripolyphosphate and Sodium Chloride Solution with Constant Stirring (Credit: J.M. Wigglesworth)

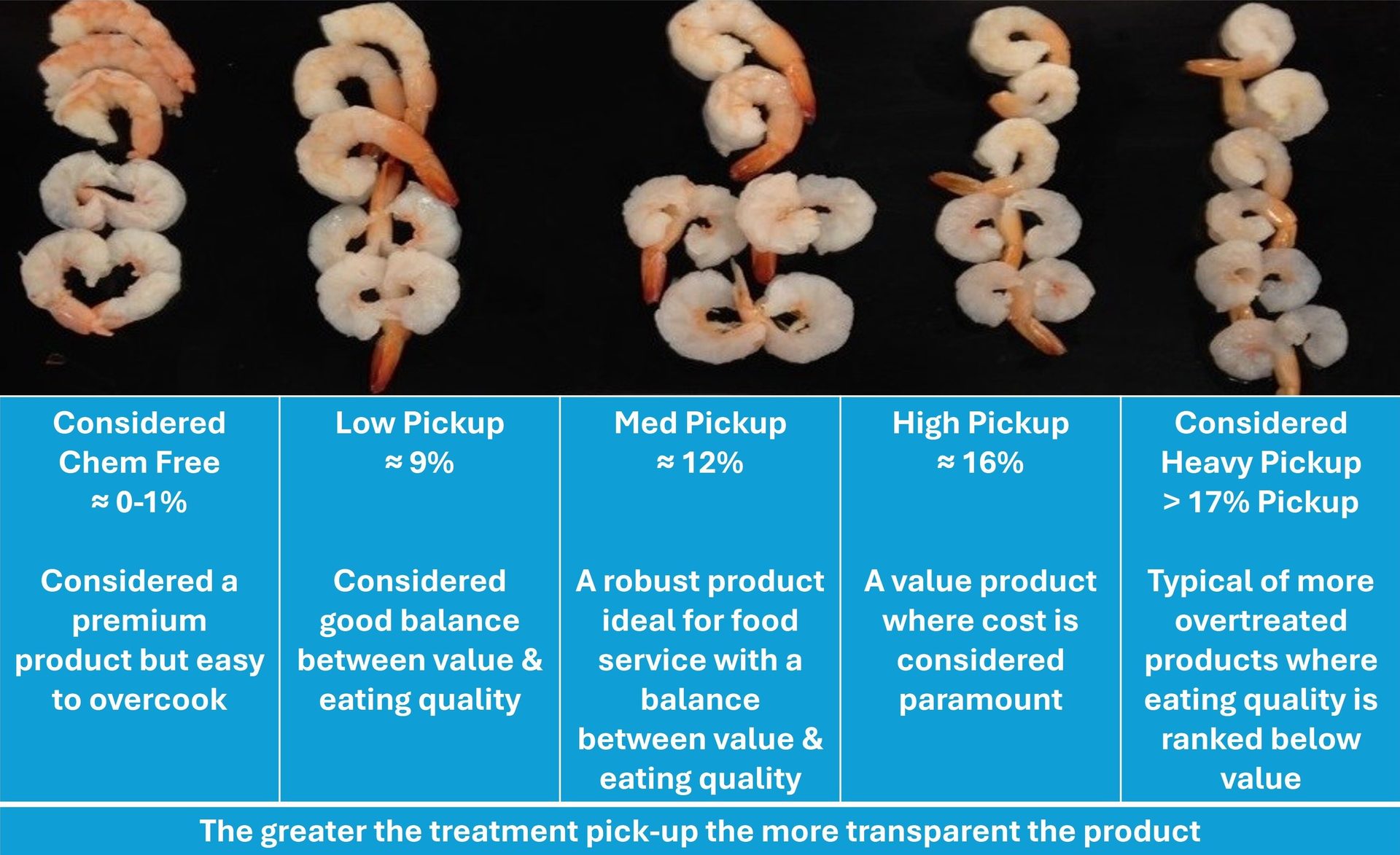

Water weight gain occurs because phosphates raise the pH of the shrimp muscle fibers from neutrality, causing them to create intra-protein voids that absorb water. Sodium chloride makes myofibrillar proteins more soluble, increasing water binding capacity.7 While numerous additive formulations and processing conditions can be used, the most common include 2 percent sodium tripolyphosphate plus 2 percent sodium chloride for approximately 2 hours. However, this combination is often refined to target certain levels of water gain by obtaining a known sample weight at the start of the process and repeating the weighing process every 20–30 minutes. In this way, weight gain (or "pickup") can be achieved with high accuracy, meeting the price agreements for the product (Figure 11).

FIGURE 11. Soaking Treatment Guide Between Untreated and Heavily Treated Products (Credit: J.M. Wigglesworth)

After the shrimp are soaked to pick up water, they are washed in a chlorine solution (10 ppm) to reduce bacterial loading, which tends to increase during this process

Cooking

While raw shrimp are processed and sold as either block (5 lb) or individually quick frozen (IQF) product, there are material streams that can be designated for generating cooked IQF products.

The cooking process is completed using steam in two- or three-compartment steam cookers that can process up to 5 metric tons per hour to achieve a 6-log reduction with the target pathogen being Listeria monocytogenes and an internal meat temperature of 70 °C for 2 minutes. The cooking process starts with secondary processed shrimp being transferred to a holding tank kept at 3–5 °C and then conveyed to an infeed belt before entering the steam oven (Figure 12).

FIGURE 12. Three-Chamber Steam Cooking Equipment (Credit: J.M. Wigglesworth)

The belt usually has personnel to smooth the product into a single layer so that all the shrimp gets cooked evenly, leaving no raw product during the cooking process. Overloading of the cooking infeed belt will lead to undercooked shrimp (Figure 13).

FIGURE 13. Undercooked Shrimp Caused by Exceeding Infeed Capacity (Credit: J.M. Wigglesworth)

The cooking process is organized so that raw and cooked products are segregated between low- and high-care areas, with separate entrances for workers wearing uniforms that are specific to the high-care area. The cooking process is stopped by discharging into an ice bath of 3–5 °C using ice from dedicated high-care equipment (Figure 14).

FIGURE 14. Discharge from High-Care Mechanical Freezer (Credit: J.M. Wigglesworth)

Listeria monocytogenes is the target organism for the pasteurization process, since it is the most heat-tolerant, non-spore-forming pathogen. Safety is managed through segregation after cooking using separate IQF machines, weighing and packing stations, and metal detection. It is possible to utilize different cooking parameters (Table 4) after calculating thermal equivalence to 70 °C for 2 minutes, but any deviations from the 70 °C internal temperature for 2 minutes must be verified using temperature and time logging on the cooking equipment being used.

TABLE 4. Thermal Equivalence to 70 °C/2 Minutes for 6-Log Inactivation of Listeria monocytogenes

Cooking at lower temperatures for longer times has been reported to enhance texture, reduce water loss, increase moisture, and improve flavor.8

Freezing, Glazing, and Packing

Freezing of shrimp can occur through IQF or block freezing (block). IQF can involve direct impingement using liquid carbon dioxide (CO2) (–70 °C to –50 °C) or liquid nitrogen (N2) (–107 °C to –95 °C) in an IQF tunnel, or IQF mechanical freezing using forced cold air from the factory's ammonia refrigeration system (–40 °C to –30 °C) in a spiral or tunnel freezer. Selection of the equipment depends on space, cost, and efficiency. IQF freezing with CO2 or N2 is more common but results in single use of gas, whereas the forced air in a spiral utilizes that factory's existing compressors and ammonia.

Block freezing involves packing shrimp into a 5-lb (2.27-kg) block using a stainless-steel tray with the addition of a small amount of water. The trays are loaded into a blast or a plate freezer operating at –4 °C. Block is less common but is ideal if the product, usually raw, is prepared for further processing with the final customer. IQF is ideal for end-use applications such as retail, wholesale, or foodservice.

IQF results in the generation of small ice crystals that damage the shrimp cells less, resulting in greater fluid retention, which improves flavor and maintains weight.

Glazing involves covering the frozen IQF product with a water glaze that protects the product from moisture migration. Migration of moisture causes freezer burn due to sublimation of water from the surface of the shrimp, making the meat look white and dry (Figure 15).

FIGURE 15. Freezer Burn and Dehydration (Credit: J.M. Wigglesworth)

Glaze can be applied manually via dipping frozen shrimp into ice-chilled water (Figure 16), or via curtain glazing, where frozen shrimp leaving the IQF are conveyed through a falling curtain of ice water. The IQF pieces then tumble onto a second belt to receive a second curtain glaze. Alternatively, IQF pieces may enter a tunnel hardener, where they are exposed to cold air before receiving a second glaze.

FIGURE 16. Manual Glazing (Credit: J.M. Wigglesworth)

Regardless of the process used, the objective is to deposit a water glaze of 10–20 percent depending on the size of the shrimp. While it is easier to deposit more glaze on smaller-size shrimp, it is more important to deposit more glaze on larger sizes, which command higher prices and more value.

The last stage in this step is weighing the product into final packaging. Like glazing, this can occur manually (Figure 17) or automatically using multi-head weighing systems. Selection of the process depends on cost and efficiency considerations. In some countries, such as those in Asia, labor costs are relatively low, so manual weighing and packing can be achieved more efficiently than in countries where labor costs are greater (such as Ecuador) and outweigh the high capital costs of multi-head systems.

FIGURE 17. Manual Packing (Credit: J.M. Wigglesworth)

After packing and sealing, the packs are sent though metal detection and/or X-ray systems as a critical control point (CCP) to control foreign objects.

Labeling and Storage

The final stages of shrimp processing involve labeling and storage. All finished consumer-facing packs and master cartons require labeling of all ingredients. For commodity raw or cooked product, the ingredients list includes shrimp, water, salt, sodium tripolyphosphate (to retain moisture), and sodium metabisulphite (used as a preservative).9 Processors are also required to identify allergens and sensitizers, which usually consists of shrimp and/or sulfite. The ingredient list can be extended depending on the finished state of the final product, with breaded value-added shrimp generating an extensive list of ingredients.

The inclusion of sulfites depends on whether the live, head-on raw material was treated with sodium metabisulfite to avoid the generation of black spots caused by the action of the enzyme polyphenol oxidase on the amino acid tyrosine, which occurs most rapidly in the head of the shrimp postmortem and causes unsightly black discoloration. Sometimes, when a batch of raw material is treated with sodium metabisulfite at harvest and size selection has occurred for head-on product, the balance of the raw material is deheaded, leaving sulfite residue in the tail. This residue must be labeled at levels greater than 10 ppm but cannot exceed 100 ppm.10

All finished frozen products are then stored in cold storage at –22 °C to –18 °C, under stable conditions, to support the shelf-life requirements up to 24 months. These requirements are established for quality rather than safety parameters.

The final component, while not strictly associated with processing, is the maintenance of stable frozen temperatures during shipping to final destinations. While this may seem to be out of the scope of shrimp processing, it is an important component that can have significant effects on the quality of the finished product due to temperature variations in the shipping containers.

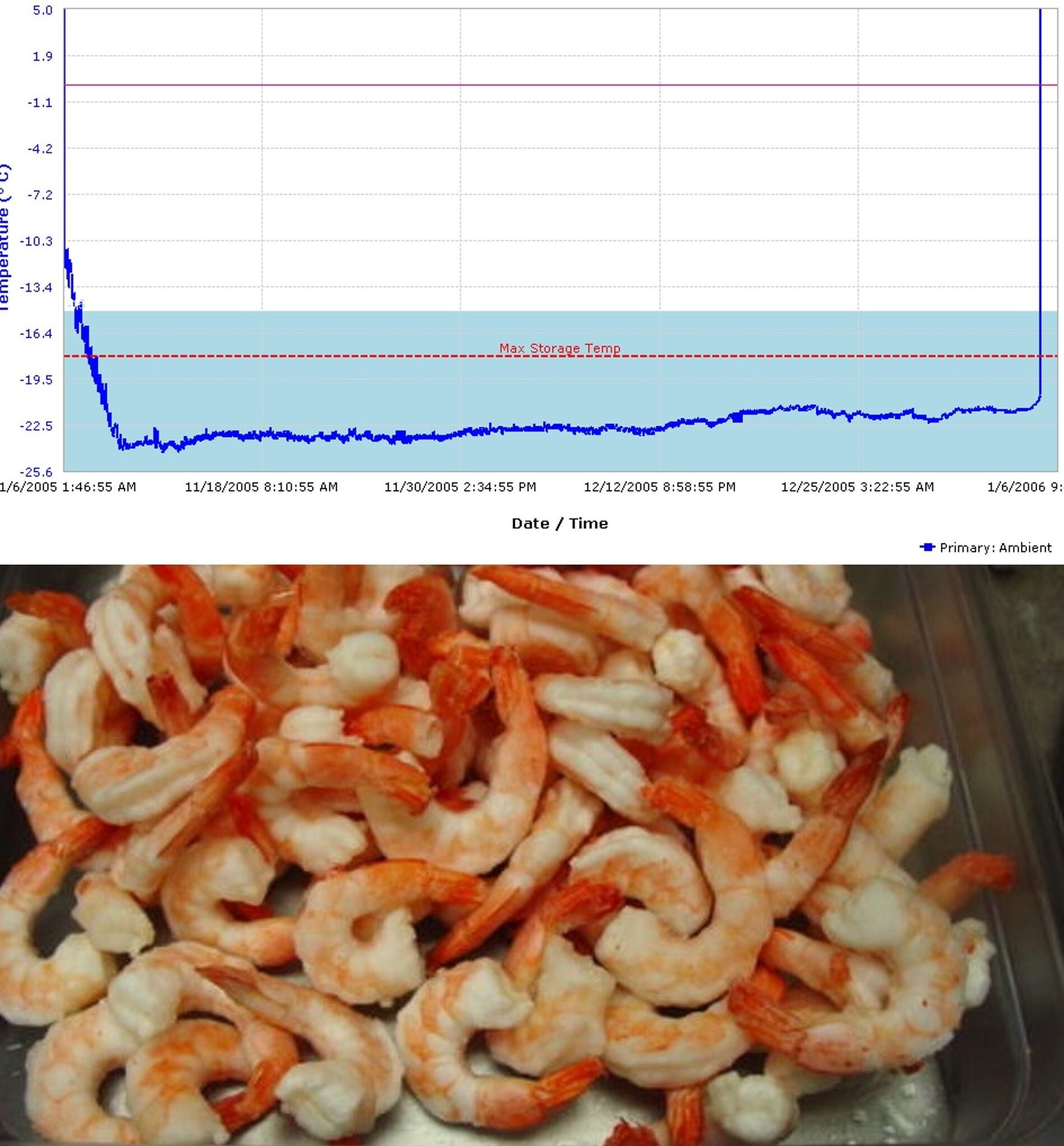

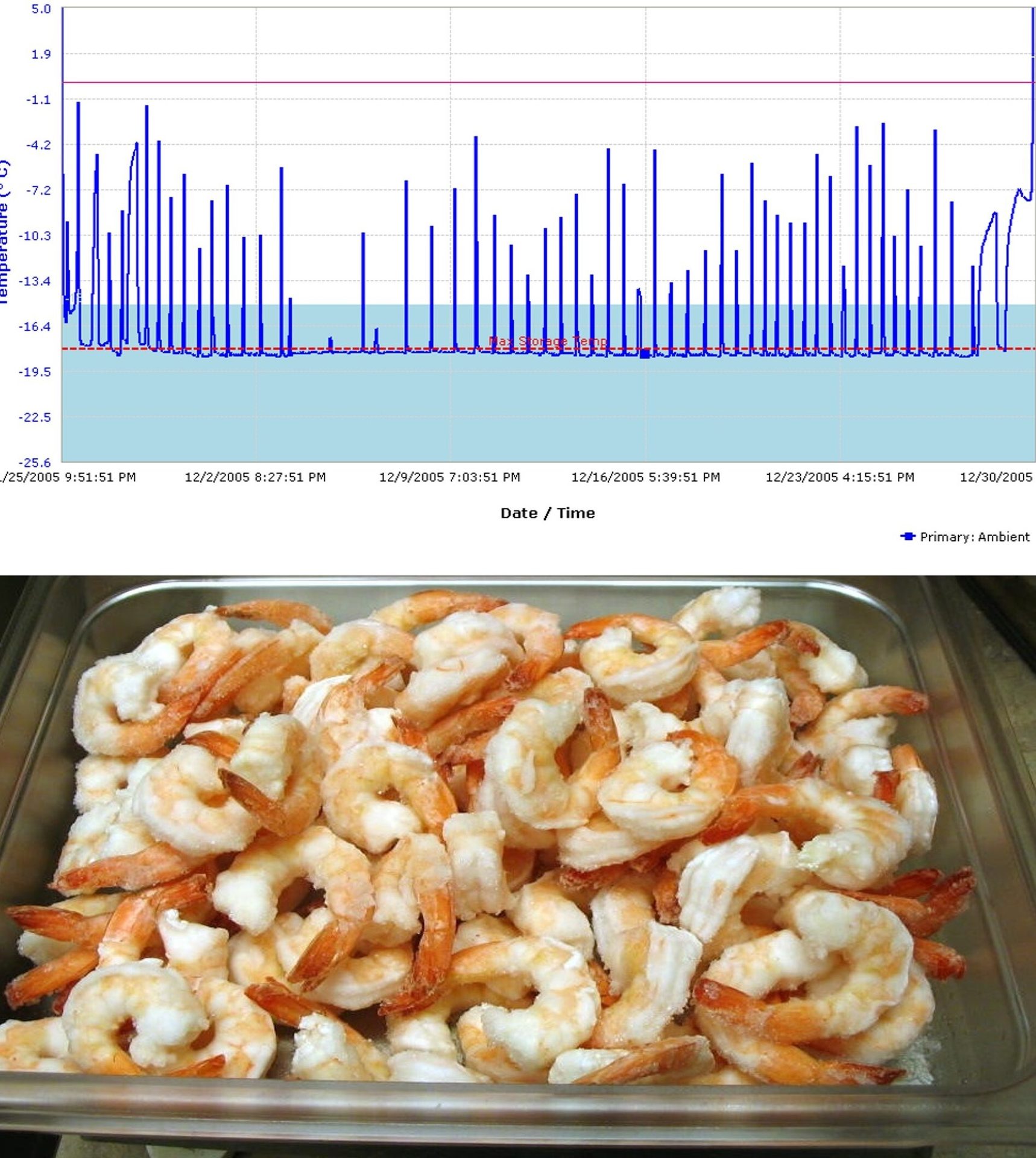

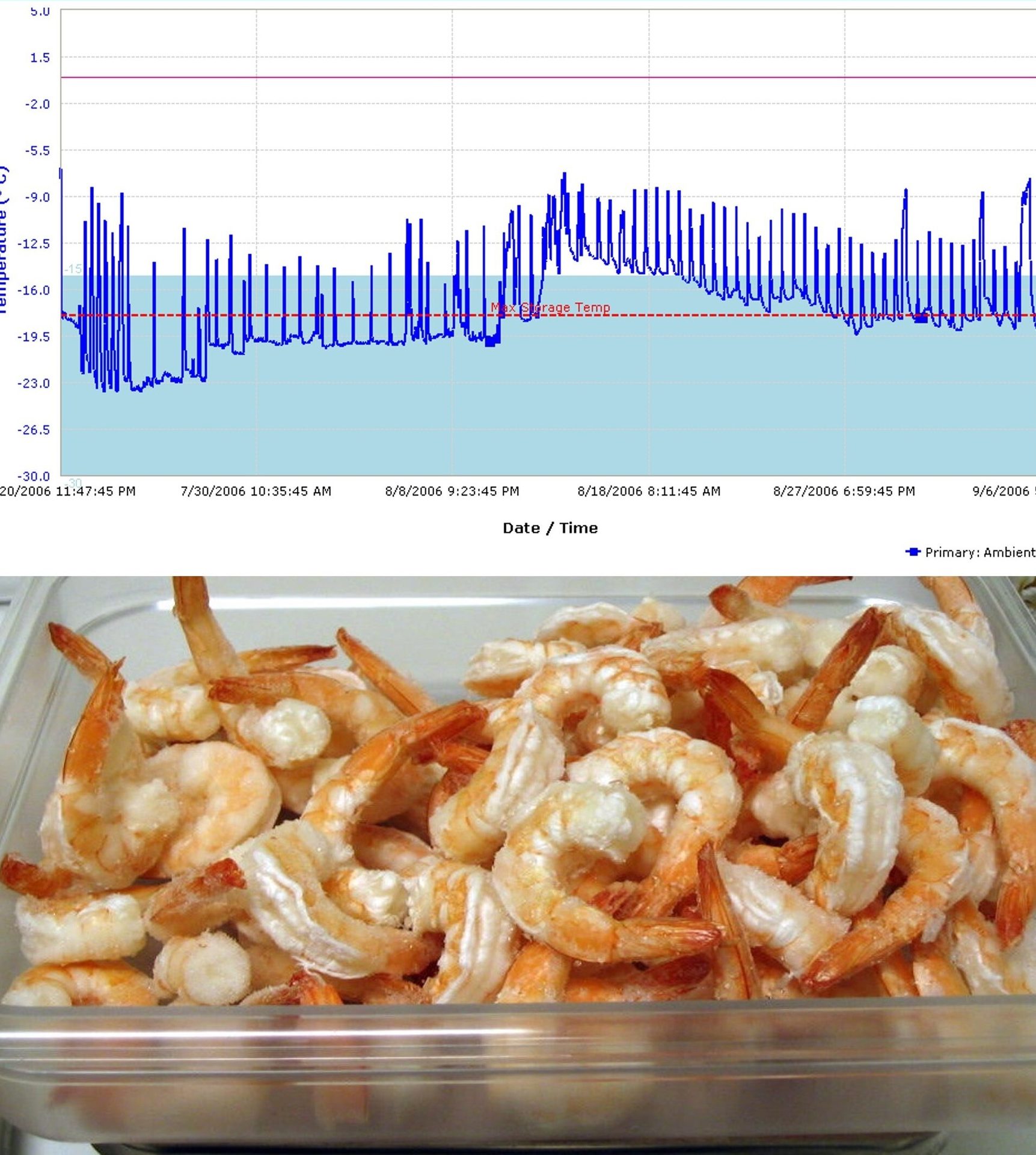

Figures 18–20 show actual temperature profiles for trans-ocean shipments of cooked IQF shrimp over 4–5-week periods.

FIGURE 18. Demonstrates a Stable Shipping Temperature Profile that Resulted in No Product Damage Such as Freezer Burn or Clumping of Product (Credit: J.M. Wigglesworth)

FIGURE 19. Demonstrates Marginal Temperature Control with Multiple and Repetitive Temperature Spikes Over a 4-Week Period (Credit: J.M. Wigglesworth)

FIGURE 20. Shows the Effect of Erratic Temperature Control on a 7-Week Shipment of Cooked IQF Causing Extensive Product Damage (Credit: J.M. Wigglesworth)

The issue of temperature control during shipping has been prevalent for many years, causing quality problems of freezer burn and dehydration. The issue affects retail packs up to 2 lb more often than foodservice bulk packs of 6–24 lb.

While the effects of variable temperature control are self-evident, the root cause has been the subject of discussion with shipping companies. One explanation has been associated with "defrost cycles," while another has been linked to the refrigerated container settings of "continuous" vs. "cycle sentry" temperature operation.

Defrost Cycles

The defrost cycle occurs because frost builds up on the evaporator coils during normal operation. Frost reduces effective operation, resulting in temperature inconsistencies inside the container. When the unit enters the defrost cycle, the air distribution fans cease operation and hot refrigerant gas is pumped through the evaporator coils to melt the frost.

The defrost process can occur as frequently as every 30 minutes and ends when the coil temperatures reach 14–21 °C, which then prompts the air distribution fans to restart. If there is no delay programmed to allow evaporator coils to regain ≤ –18 °C temperature, then air up to 21 °C is circulated in the container, which causes temperature cycling.

Continuous vs. Cycle Sentry Modes in the Refrigeration Unit

The "continuous" setting allows for a consistent temperature throughout the trailer for the duration of operation and results in better temperature management because the unit does not switch off when the set point of –18 °C or lower is reached. The "cycle sentry" mode operates like a thermostat and switches the unit off when the set point is reached, resulting in greater temperature variation in the container.11

“Quality management is arguably as important as safety considerations, given the high water activity of the raw material and the speed of rapid deterioration being accelerated due to spoilage organisms, neutral pH, enzymic action, and delicate protein structure.”

Takeaway

Shrimp processing is no more complex than processing other foods such as poultry, pork, or beef, with shared similarities of sourcing, cleaning, sorting, and processing to achieve a stable product for distribution and sale. In many respects, shrimp processing bears more similarity to fresh produce processing. The two commodities have similar requirements for rapid processing and maintaining cold temperatures due to the high water content, as well as the demand of continuous washing in chlorinated water to reduce bacterial loads.

Shrimp processing is, however, relatively complex from the standpoint of the range of products that are created from a single batch of raw material including head-on, head-off, peeled, butterflied, sushi, raw, cooked, and breaded, to name but a few end products. The common denominator in all these products is the requirement to adhere to the seafood industry maxim of "wash it often, keep it cold, and move it quickly." Apart from cooked or high-pressure processed (HPP) product, there are no other kill steps in the process to eliminate microbiological pathogen risks, which can only be effectively managed by adherence to those generally adopted rules.

Chemical safety controls revolve around antibiotic/chemical testing of pre-harvest shrimp and raw material upon arrival at the factory, with general bacterial loads managed though temperature control and frequent washing. Finished product testing is the final verification step before releasing safe and wholesome product. Cooked products are produced through adherence to established pasteurization methods, with product segregation being strictly followed and enforced.

Quality management is arguably as important as safety considerations, given the high water activity of the raw material and the speed of rapid deterioration being accelerated due to spoilage organisms, neutral pH, enzymic action, and delicate protein structure. That same quality management must be extended into cold chain handling due to the susceptibility of the product to moisture migration and sublimation of water from the glaze, which leave the protein vulnerable to dehydration and freezer burn.

So, what is the future for shrimp processing? The shrimp industry is evolving in response to cost efficiency comparisons between traditional processing methods and new methods requiring equipment investment. The primary driver to make those changes will always depend on the high capital cost of new equipment vs. the existing labor costs and projections over the next 10 years.

Interest has also emerged in monetizing shrimp waste streams. This makes practical sense, since every metric ton of shrimp raw material generates 350 kg of head waste and 150 kg of shell if the product is peeled. This waste has the potential to be converted to chitin bioplastics, carotenoids, flavorings, oils, and proteins,12 depending on the appetite for capital investment into redirecting waste streams into byproducts. Some larger, vertically integrated processors already do this, but it is more challenging for smaller processors with fewer resources. Regardless, profitability often drives innovation and invention, making waste stream product development the most profitable shift in expanding the shrimp processing income stream.

Note

The findings and conclusions of this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). "Globefish: Quarterly Shrimp Analysis." May 2025. https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/cd5727en.

- Aquaculture Magazine Editorial Team. "Global Scenario of Shrimp Industry: Present Status and Future Prospects." April 28, 2025. https://aquaculturemag.com/2025/04/28/global-scenario-of-shrimp-industry-present-status-and-future-prospects/.

- IMARC. "Shrimp Market Size, Share, Trends and Forecast by Environment, Species, Shrimp Size, Distribution Channel, and Region, 2025–2033." 2025. https://www.imarcgroup.com/prefeasibility-report-shrimp-processing-plant.

- Jory, D. "Global shrimp production forecast of 5.6 million metric tons is slightly lower for this year." Global Seafood Alliance. October 9, 2023. https://www.globalseafood.org/advocate/annual-farmed-shrimp-production-survey-a-slight-decrease-in-production-reduction-in-2023-with-hopes-for-renewed-growth-in-2024/.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Fish and Fishery Products Hazards and Controls: June 2022 Edition. Content current as of August 1, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/food/seafood-guidance-documents-regulatory-information/fish-and-fishery-products-hazards-and-controls.

- Chakma S., S. Susmita, N. Hossain, et al. "Effect of frozen storage on the biochemical, microbial and sensory attributes of Skipjack Tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis) fish loins." Journal of Applied Biology and Biotechnology 8, no. 4 (2020): 58–64.

- Carneiro, C.S., E.T. Marsico, R. Oliveira Resende Ribeiro, et al. "Studies of the effect of sodium tripolyphosphate on frozen shrimp by physicochemical analytical methods and Low Field Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (LF 1H NMR)." Food Science and Technology 50, no. 2 (2013): 401–407.

- Das, R., N.K. Mehta, S. Ngasotter, et al. "Process optimization and evaluation of the effects of different time-temperature sous vide cooking on physicochemical, textural, and sensory characteristics of Whiteleg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei)." Heliyon 9, no. 6 (June 2023): e16438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e16438.

- Weddig, L. "Labeling Shrimp Products." National Fisheries Institute, NFI Shrimp School. November 12, 2020. https://aboutseafood.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Labeling-Shrimp-Products_Lisa-Weddig-National-Fisheries-Institute.pdf.

- FDA. "Chapter 19: In Fish and Fishery Products Hazard and Controls Guidance." Food and Color Additives, 3rd Ed. FDA Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN), Office of Seafood, 2001: 237–248.

- Thermo King. "Thermo King Operators Manual: Precedent Single Temperature Units C-600, S-600 and S-700." 2021. https://www.thermoking.com/content/dam/thermoking/documents/technical-literature/TK-56218-1-OP-EN-Precedent-Single-Temperature-Units.pdf.

- Thamrin, N.M., R.M. Ilmi and A. Hasizah. "Potential and Trends Processing of Shrimp Industry By-Products in Food: A Review." BIO Web of Conferences 96 (2024): 01008. https://doi.org/10.1051/bioconf/20249601008.

John M. Wigglesworth, Ph.D., REHS/RS, CPFS, PCQI is a retired seafood technologist and consultant with over 34 years of experience working in the seafood sector. He holds advanced degrees in Food Science and Technology and professional registrations in Food Safety and Public Health. After completing his Ph.D., he served as Technical Director for Ecuadminsa SA, a vertically integrated shrimp company in Ecuador. He then moved to Central America and worked for Seafarms International as Technical Director for the company's aquaculture and processing operations in Honduras, Venezuela, and the U.S. He has worked for seafood importers Mazzetta Company LLC and Chicken of the Sea Frozen Foods, sourcing seafood globally to supply foodservice, retail, and club outlets. He also worked for two Fortune 500 restaurant companies, Darden Restaurants and Brinker International, and a grocery retailer, Southeastern Grocers, with senior technical responsibility for seafood and other food products. His last position was Head of Supply Chain Assurance for the Aquaculture Stewardship Council in the Netherlands.