SUPPLY CHAIN

By Ahmed G. Abdelhamid, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, Food Microbiology, Michigan State University

Revisiting the Safety of Fresh Produce from Field to Fork

Pathogen contamination and mitigation strategies for sprouts and cucumbers are critically reviewed

Image credit: vaaseenaa/iStock/Getty Images Plus via Getty Images

SCROLL DOWN

Fresh produce refers to raw agricultural commodities including fruits, vegetables, herbs, and edible plant parts (e.g., roots like carrots, shoots like asparagus, leaves like lettuce, and fruits like tomatoes and cucumbers) that are consumed in a state close to harvest with minimal processing. The fact that most produce is eaten without a validated kill step explains why contamination events translate into large and multi-state foodborne outbreaks.

Traceback activities conducted during outbreak investigations repeatedly implicate leafy greens (e.g., romaine lettuce and spinach), melons, onions, cucumbers, tomatoes, fresh herbs, and sprouts, among others, as vehicles of pathogen contamination.1 These foods are grown in open or semi-open environments, frequently irrigated, and handled significantly. Contamination can occur anywhere from seed to fork. Sources of pathogen contamination often include factors in the fresh produce growing environment such as irrigation water, wildlife and domestic animal intrusion, proximity to animal operations, worker health and hygiene practices, and the use of biological soil amendments of animal origin such as untreated manure.2

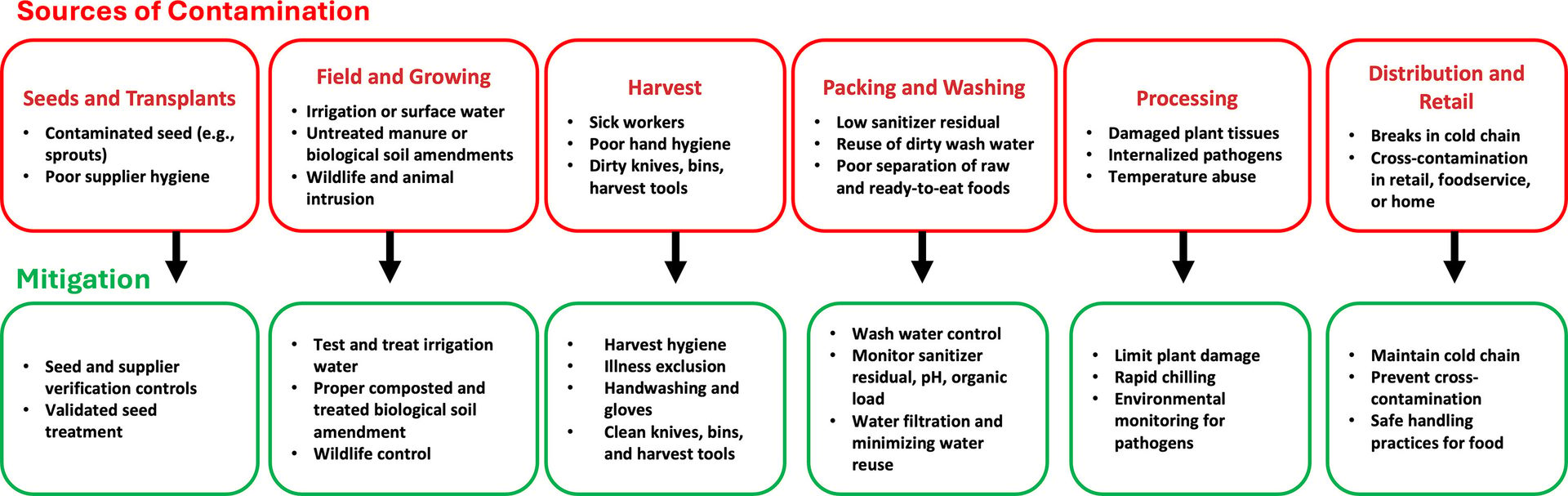

At the post-harvest stage, cross-contamination could be partially attributed to insufficient disinfectant residuals,3 reuse or recirculation of wash water without effective filtration and sanitization, or inadequate separation between raw and ready-to-eat foods. Sanitizing washes (e.g., chlorine, peracetic acid, chlorine dioxide, and ozone) are essential. Even under best practice, however, they do not effectively reach bacteria that have internalized into fruit and vegetable tissues, and high organic loads rapidly quench oxidizing sanitizers. Wash water disinfection is necessary to prevent cross-contamination but not sufficient to fully decontaminate fresh produce. A comprehensive summary of sources of pathogen contamination and methods of mitigation is illustrated in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1. Sources of Pathogen Contamination and Methods of Mitigation (Credit: A. Abdelhamid)

Pathogens of Concern and Biological Challenges that Complicate Control

Three pathogens dominate produce-related outbreaks.2 Salmonella enterica is ecologically versatile, capable of adhering to and colonizing the phyllosphere and rhizosphere plants, and some serovars are more capable of persisting in soil and water. Certain serovars (e.g., Newport and Poona) exhibit strong produce-specific colonization. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) has a low infectious dose and is known to be associated with cattle as reservoirs; environmental transfer to field-grown crops is plausible. Listeria monocytogenes is a hardy environmental pathogen that thrives in cool and wet packinghouse environments. It may be difficult to eliminate through sanitation and environmental monitoring interventions alone.

Pathogens have physiological changes (e.g., internalization and biofilm) that facilitate their colonization of fresh produce. These biological phenomena include internalization, which refers to entry through plant natural openings.4 Cut melons, tomatoes, and cucumbers possess nutrient-rich niches that support growth for internalized pathogens if temperatures are not controlled. Biofilms (particularly mixed species) growing on equipment and in drains protect pathogens against sanitizers and cause recurring contamination. In viable but nonculturable (VBNC) states, stressed bacterial cells remain infectious and viable yet evade standard culture-based testing.5

The food matrix also impacts pathogen infectious doses, which are inferred from clinical or volunteer studies, but the infectious dose determined in a given food matrix (e.g., spinach) may not translate to others such as lettuce, melons, or cucumbers. Food fat, pH, surface chemistry, and native microbiota can suppress or enhance pathogen survival and virulence. Overall, the physiological changes of foodborne pathogens and their interaction with the food matrix are highly variable and intertwined. A clear understanding of the behavior of pathogen–food interactions is an asset.

Sprouts and Cucumbers: Two Instructive Fresh Produce Models

In the following sections, two models of fresh produce commodities are discussed:

- Sprouts, for which the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued commodity-specific guidance

- Cucumber as an example of fresh produce that currently lacks such specific guidance.

For each food, the risk of pathogen contamination and mitigation strategies are critically reviewed.

Food Safety Challenges of Sprouts

Sprouts are unique food commodities because the seed is the ingredient and sprouting conditions include warmth, moisture, and nutrients, which are ideal for pathogen proliferation. If a seed lot carries even a low level of contamination (e.g., 10–100 cells per gram of seed), then the sprouting process allows growth of the pathogen by orders of magnitude. Seed disinfectants (e.g., calcium hypochlorite) reduce risk but cannot guarantee full food sterility. It is particularly difficult to eliminate internalized pathogen cells. Testing of the spent irrigation water provides an earlier detection point than end-product sampling, but negative tests are not absolute proof of safety due to sampling limitations.

Due to the unique risks associated with sprouts, FDA's FSMA Final Rule on Produce Safety (the Produce Safety Rule) established sprouts-specific requirements.6 Three core points of sprout safety are discussed below: seeds, water, and batch-level testing.

Seed treatment. Seeds are recognized as the primary source of pathogen contamination for sprouts. Contamination is often at a low level and unevenly distributed; however, sprouting creates ideal conditions for pathogen growth. Therefore, seeds used to grow sprouts are required to be treated using a scientifically valid method that reduces microorganisms of public health significance [§112.142(e)].6

A risk assessment model7 for alfalfa sprouts shows that without any seed treatment or spent sprout irrigation water testing, about 5.22 percent of sprout batches are predicted to be contaminated with Salmonella. Seed treatment alone reduces this risk to 2.32 percent, 0.032 percent, or 0.00032 percent in the case of achieving 1-, 3-, and 5-log reduction of the pathogens, respectively. According to that same study,7 there would be about 76,600 salmonellosis cases per year from contaminated sprouts if no interventions are implemented. Combining a 5-log reduction by seed treatment with effective spent sprout irrigation water testing yields an estimated 99.9994 percent reduction in cases. A 3-log reduction plus water testing reduces cases to 45 per year, whereas water testing alone would still result in 12,100 cases per year.7 On this basis, using a seed treatment that achieves at least a 3-log reduction would be impactful for safety.

“Avoiding the reuse of contaminated spent irrigation water prevents amplification and spread of pathogens from one small contamination event to a large volume of product.”

At present, investigated seed treatment methods include physical (e.g., dry heat, hot water, high pressure, irradiation), chemical (e.g., sodium hypochlorite, acidified sodium chlorite, hydrogen peroxide, organic acids), and combination treatments (e.g., chemical plus physical).

Water quality and reuse. Water used to prepare seed treatments and for rinsing/soaking seeds before or after disinfection treatment is referred to as agricultural water and must contain no detectable generic E. coli in 100 mL (§112.44[a]).6 Containers, tools, and equipment contacting seeds must be cleaned and sanitized before use. It is recommended not to reuse spent sprout irrigation water from one batch to irrigate subsequent batches, or even the same batch over time, unless it is appropriately treated. Reuse of untreated water can spread any contamination to a larger fraction of the sprout product.

Spent sprout irrigation water. For every individual production batch, the growing, harvesting, packing, and holding environments should be tested for Listeria species or L. monocytogenes, while the sprout irrigation or spent water should be tested for Salmonella and E. coli O157:H7 (§112.144[c]).6 If spent irrigation water tests positive, then the affected batch must be prevented from entering the market and corrective actions must be taken.

Avoiding the reuse of contaminated spent irrigation water prevents amplification and spread of pathogens from one small contamination event to a large volume of product. Growers must routinely test and manage water to meet the criteria. In practice, sprout producers should implement a multi-hurdle system through scientifically valid seed treatment (≥ 3-log reduction, whenever possible). Compliance is required for water quality and equipment sanitation, as well as robust testing of spent irrigation water and sprouts themselves. This integrated approach could meaningfully reduce the risk of contamination and illness due to sprouts consumption.

Food Safety Challenges for Cucumbers

Cucumbers are often field-grown, trellised or on the ground, irrigated, and handled rapidly post-harvest. Potential contamination routes include the irrigation water, soil, and aerosols during overhead irrigation; wildlife intrusion; and contaminated harvest bins or packing lines. Cucumbers are a covered fresh produce under the Produce Safety Rule because they are commonly consumed raw. A microbiological surveillance study found Salmonella in 1.75 percent of 1,601 cucumber samples, with similar prevalence in domestic and imported products, but no pathogenic E. coli detected.8 Recurring multistate Salmonella outbreaks linked to field cucumbers in 2015–2016 and again in 20249 emphasize that cucumbers serve as a vehicle for foodborne infection when eaten raw.

Although FDA has no cucumber-specific guidance analogous to the 2023 sprout guidance, cucumber farms and packinghouses must comply with the Produce Safety Rule standards, which include:

- Worker training and hygiene

- Agricultural water management for pre-harvest and post-harvest uses, including ensuring that water used for washing, fluming, or cooling meets microbial quality requirements and is treated and monitored when necessary

- Management of biological soil amendments of animal origin (e.g., using properly treated manure or managing timing and application practices for untreated amendments)

- Animal intrusion control, particularly for open fields

- Cleaning and sanitizing of harvest tools, bins, conveyors, brushes, dump tanks, and other food contact surfaces.10

Post-harvest washing and sanitizing of whole cucumbers is a control step available to packers. Multiple studies have characterized achievable log reductions under realistic processing conditions. Li et al. showed that a triple-wash procedure (water–water–antimicrobial) using 100-ppm sodium hypochlorite or acidified sodium hypochlorite, a 2.5 percent lactic acid/citric acid blend, or a peroxyacetic acid (PAA)/H₂O₂ formulation (0.006–0.50 percent) for three 10-s dips at 15 °C reduced a Salmonella cocktail on cucumbers by nearly 2.0–2.8 log CFU/fruit, significantly more than water-only washing.11

Yuk et al. reported that 200-ppm free chlorine, 1,200-ppm acidified sodium chlorite (ASC), or 75-ppm PAA achieved 5.0-log reductions relative to non-sanitized cucumbers that were inoculated on smooth surfaces.12 More recently, Benitez et al. showed that washing inoculated cucumbers in 100-ppm chlorinated water with aeration for 3 minutes reduced S. enterica from 4.45 log CFU/cm2 to below the detection limit (0.16 log CFU/cm).13

“Produce Safety Rule compliance for cucumbers must prioritize pre-harvest prevention, while post-harvest treatments can be viewed as a finishing step rather than a kill step.”

However, surface sanitization alone is not sufficient. Salmonella can colonize the rhizosphere and internal tissues of cucumber plants. Thus, Produce Safety Rule compliance for cucumbers must prioritize pre-harvest prevention (e.g., water quality, animal exclusion, management of biological soil amendments, etc.), while post-harvest treatments can be viewed as a finishing step rather than a kill step.

Mitigation of Pathogen Contamination Risk in Fresh Produce

Integrated risk management from farm-to-fork is an essential strategy to substantially reduce pathogen contamination through the fresh produce supply chain (see Figure 1). Key elements include sourcing seeds and transplants from suppliers with documented hygiene and pathogen preventive controls, including validated seed treatments where applicable. It is also important to treat all water used for irrigation, washing, cooling, and fluming as a control point where the source (e.g., surface, ground, municipal, recycled water) should be known and a validated treatment (e.g., disinfection) should be implemented, specifically when the risk of water contamination is high.

A further strategy for reducing contamination is eliminating raw manure on fields intended for ready-to-eat fresh produce and instead using properly composted and/or treated biological soil amendments. Other critical steps for mitigating the risk of pathogen contamination include monitoring and control of wildlife intrusion; avoiding grazing or pasturing near produce fields; enforcing worker health, hygiene, and training; and ensuring that equipment is sanitized.

Knowledge Gaps that Warrant Attention

To move beyond incremental improvements, several critical knowledge gaps need to be addressed. Robust data are lacking for pathogen infectious doses associated with fresh produce tissues. Knowing what agricultural and processing practices and environmental conditions promote or limit bacterial entry and survival within fresh produce tissues could lead to the development of management or processing strategies that aim to minimize pathogen internalization.

How often VBNC pathogen states contribute to risk in fresh produce is uncertain, and such concern mandates designing practical viability assays that can distinguish viable from non-viable cells and better predict illness earlier in the fresh produce supply chain. Standardizing microbial challenge and recovery experiments, which are often food commodity-specific, would allow for direct comparison of interventions across regions and countries.

A Realistic Overall Perspective

Fresh produce safety is a global issue driven by growing demand for minimally processed, ready-to-eat foods. Countries vary in agricultural water infrastructure and regulatory capacity, but the biology of foodborne pathogens does not change. In lower-resource settings, improving the quality of water used for irrigation and postharvest processing, providing infrastructure for worker hygiene and safety training, and implementing good agricultural practices will enable a large safety gain. In high-resource settings, better process control, implementation of rapid detection methods, robust traceability systems, and timely response to foodborne illness outbreaks and other contamination events will further improve fresh produce safety.

“Each step in the 'rings of defense' must be used consciously and with proper consideration, as it may be obvious what caused the noncompliance, and its resolution may be straightforward, simple, and not costly.”

References

- Carstens, C.K., J.K. Salazar, and C. Darkoh. "Multistate Outbreaks of Foodborne Illness in the United States Associated with Fresh Produce from 2010 to 2017." Frontiers in Microbiology 10 (November 2019): 2667. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31824454/.

- Alegbeleye, O.O., I. Singleton, and A.S. Sant'Ana. "Sources and Contamination Routes of Microbial Pathogens to Fresh Produce During Field Cultivation: A Review." Food Microbiology 73 (August 2018): 177–208. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0740002017310158.

- Banach, J.L., I. Sampers, S. Van Haute, I. Van Der Fels-Klerx, M. Uyttendaele, E. Franz, and O. Schlüter. "Effect of Disinfectants on Preventing the Cross-Contamination of Pathogens in Fresh Produce Washing Water." International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 12, no. 8 (July 2015): 8658–8677. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26213953/.

- Kroupitski, Y., D. Golberg, E. Belausov, R. Pinto, D. Swartzberg, D. Granot, and S. Sela. "Internalization of Salmonella enterica in Leaves is Induced by Light and Involves Chemotaxis and Penetration through Open Stomata." Applied and Environmental Microbiology 75, no. 19 (July 2009): 6076–6086. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2753090/.

- Zhao, X., J. Zhong, C. Wei, C.W. Lin, and T. Ding. "Current Perspectives on Viable but Non-Culturable State in Foodborne Pathogens." Frontiers in Microbiology 8 (April 2017): 237514. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/microbiology/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2017.00580/full.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Guidance for Industry: Standards for the Growing, Harvesting, Packing, and Holding of Sprouts for Human Consumption. September 2023. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/guidance-industry-standards-growing-harvesting-packing-and-holding-sprouts-human-consumption.

- Chen, Y., R. Pouillot, S.M. Santillana Farakos, et al. "Risk Assessment of Salmonellosis from Consumption of Alfalfa Sprouts and Evaluation of the Public Health Impact of Sprout Seed Treatment and Spent Irrigation Water Testing." Risk Analysis 38, no. 8 (August 2018): 1738–1757. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29341180/.

- FDA. "Microbiological Surveillance Sampling: FY16-17 Cucumbers." Current as of February 25, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/food/sampling-protect-food-supply/microbiological-surveillance-sampling-fy16-17-cucumbers.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). "Investigation Update: Salmonella Outbreak, Cucumbers, November 2024." January 8, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/outbreaks/cucumbers-11-24/investigation.html.

- FDA. FSMA Final Rule on Produce Safety. November 2015. https://www.fda.gov/food/food-safety-modernization-act-fsma/fsma-final-rule-produce-safety.

- Li, K.W., Y.C. Chiu, W. Jiang, L. Jones, X. Etienne, and C. Shen. "Comparing the Efficacy of Two Triple-Wash Procedures with Sodium Hypochlorite, a Lactic–Citric Acid Blend, and a Mix of Peroxyacetic Acid and Hydrogen Peroxide to Inactivate Salmonella, Listeria monocytogenes, and Surrogate Enterococcus faecium on Cucumber." Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 4 (March 2020): 519493. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/sustainable-food-systems/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2020.00019/full.

- Yuk, H.G., J.A. Bartz, and K.R. Schneider. "The Effectiveness of Sanitizer Treatments in Inactivation of Salmonella spp. from Bell Pepper, Cucumber, and Strawberry." Journal of Food Science 71 (June 2006). https://ift.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-2621.2006.tb15638.x.

- Benitez, J.A., J. Aryal, I. Lituma, J. Moreira, and A. Adhikari. "Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Aeration and Chlorination During Washing to Reduce E. coli O157:H7, Salmonella enterica, and L. innocua on Cucumbers and Bell Peppers." Foods 13, no. 1 (December 2023): 146. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38201174/.

Ahmed Abdelhamid, Ph.D. is an Assistant Professor of Food Microbiology at Michigan State University (MSU). His research program focuses on applying microbial omics to enhance food safety and human health. In particular, his research lab studies the biology of food microbiota, the virulence and adaptive responses of foodborne pathogens, and the dynamics of foodborne pathogen biofilms.