PUBLIC-

PRIVATE

FOR SAFER FOODS

PARTNERSHIPS

> COVER STORY

Video credit: VectorFusionArt/Creatas Video+ / Getty Images Plus via Getty Images

SCROLL DOWN

Ensuring safe food is a shared responsibility that depends on capacity and collaboration across diverse public and private sector stakeholders. Experience shows that countries with more capacity to manage food safety risks have a better understanding of the importance of close cooperation between the various public and private sector stakeholders involved and are more proactive in developing and implementing partnerships. Public-private partnership (PPP) platforms in the spirit of trusted collaboration could accelerate the development process and serve as a win-win situation for the industry, competent authorities, and consumers. PPP platforms that connect diverse stakeholders with a mutual interest allow building relationships and trust that improve food safety outcomes—a win-win situation for the industry, food safety authorities, and consumers. PPP platforms also create opportunities to leverage resources, which can help bridge the financing gaps needed to achieve the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), estimated to be around US$2.5 trillion every year.1 Food safety-related platforms facilitating information exchange in public and private actors are particularly vital to have lasting positive impacts on countries’ public health and economies benefiting from enhanced food trade.

The United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) is one of several organizations in the Standards and Trade Development Facility (STDF), a partnership that convenes diverse stakeholders with a shared interest in facilitating safe trade. With longstanding experience in rolling out impactful partnerships that benefit developing countries, UNIDO’s latest collaboration with the STDF is piloting an innovative partnership approach to improve food safety outcomes using voluntary third-party assurance (vTPA) programs, based on a forthcoming Codex guidance. This work brings together public and private stakeholders involved in food safety regulation and management at the country level, as well as diverse international and regional partners. This article shares experiences and lessons about how UNIDO and the STDF have used partnerships to improve food safety, with a focus on ongoing work using the vTPA program approach.

By Gabor Molnar and Marlynne Hopper

Why Partnerships for Food Safety Matter More Than Ever

Around the world, some public and private sector stakeholders have for many years now been working in partnership to strengthen food safety outcomes. With the unprecedented disruptions caused by the coronavirus pandemic, there have been more calls for partnership approaches across diverse sectors. What can we learn about existing PPPs for food safety? And how can we further encourage innovative PPPs to generate future food safety improvements?

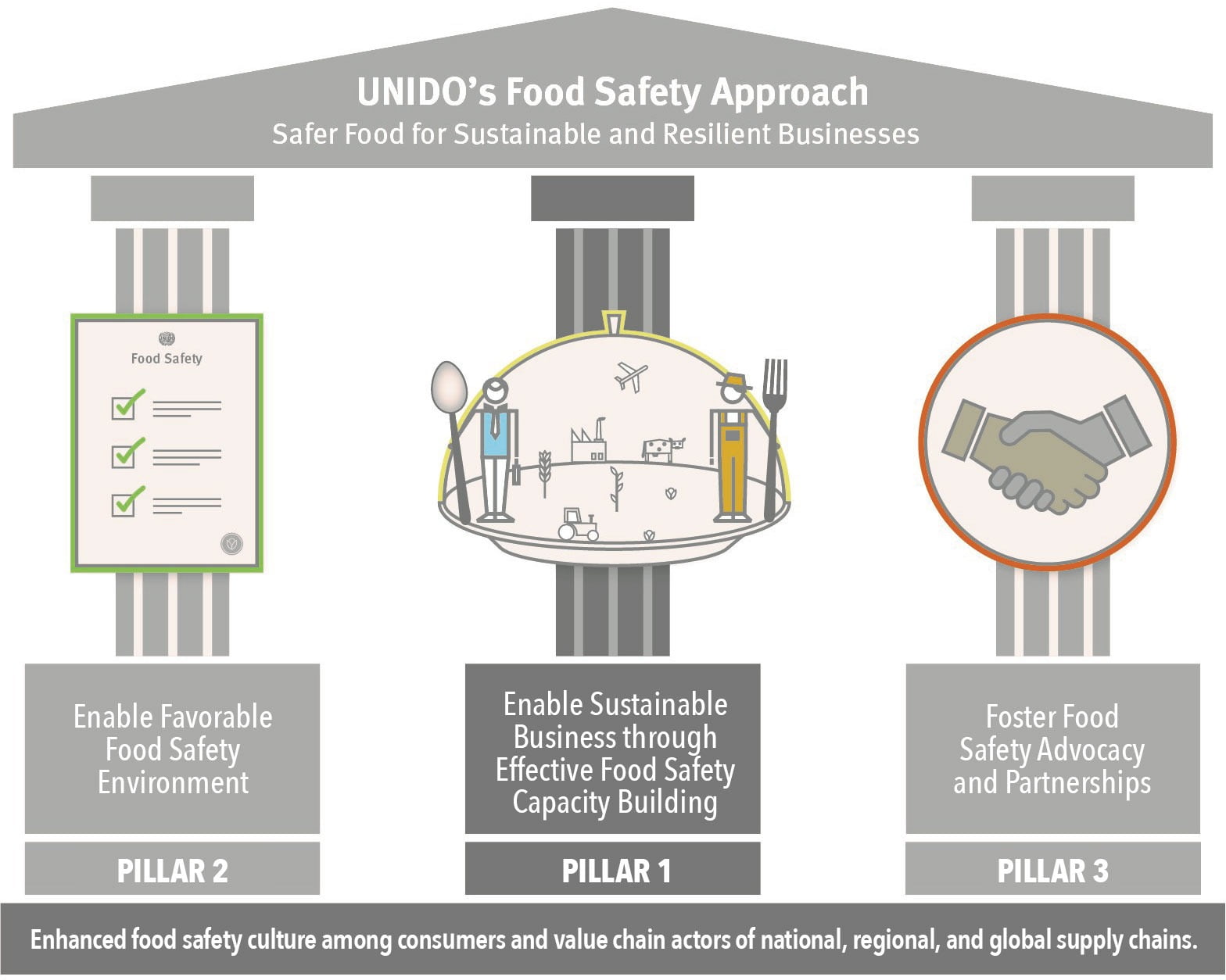

Interest in public-private sector collaboration is growing, as governments search for alternative and innovative solutions to enhance their food control system, and small and medium-size enterprises seek new markets in the high-value domestic retail sector, locally, regionally, and globally. UNIDO and the STDF have long-standing experience in facilitating PPPs to strengthen food safety capacity, promote market access, and raise competitiveness. The third pillar of UNIDO’s food safety approach2 (Figure 1) promotes the engagement of private sector actors in local, regional, and global partnerships and advances multistakeholder food safety dialogues and interventions. PPP approaches are at the heart of many STDF projects to improve capacity to meet international standards (including Codex) and facilitate safe trade3 and are also addressed in STDF’s knowledge work.

There are different types of PPPs to improve food safety capacity and compliance, involving diverse stakeholders. While some of these partnerships focus on dialogue and information exchange, others go much further to develop and roll out a collaborative approach to the planning and implementation of food safety controls, accompanied by new legal and/or financing arrangements. While it often takes considerable time and effort to develop and sustain these partnerships, experience points to the value and rewards.

FIGURE 1. Three Pillars of UNIDO’s Food Safety Approach

Key Types of PPPs in Food Safety

Roundtables or other forums for regular dialogue, information exchange, and/or coordination on food safety policy priorities and investment needs.

Such roundtables and forums can convene relevant public and private sector stakeholders around requirements affecting market access for particular value chains or more broadly on existing and new food safety issues. National Codex Committees often play this role. For instance, in Senegal, the National Codex Committee brings together different parts of government involved in food safety, as well as representatives of multinational companies and local industry and trade associations, and provides a place for ongoing dialogue and exchange that builds trust.

Public-private collaboration focusing on specific tasks. These can be technical committees that develop or revise standards, guidelines, or codes of practice based on the national context.

For instance, in Sri Lanka, government authorities joined forces with the Spice Council, a local industry and export association, to roll out vocational training on improved food safety and hygiene practices and upgrade infrastructure of local businesses.4 This boosted the productive capacities and competitiveness of the Ceylon cinnamon value chain, paving the way for transformational change in the sector. The collaboration also contributed to increased exports, potentially becoming a billion-dollar industry.

Government-business cooperation on regulatory practice to improve and promote compliance. Interest is growing in innovative models of partnerships with the food industry, which emerged in some developed countries over the last decade. This includes official recognition of some vTPA programs. Some regulatory authorities are assessing the industry’s use of such programs and certification schemes as part of their national food safety regulatory oversight frameworks, including as one factor to inform risk-based inspection and resource allocation decisions. For instance, in the UK, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France, food safety regulators now recognize certain vTPA programs and integrate the audit results into their regulatory decision-making.

What Are vTPA Programs?

The Codex Committee on Food Import and Export Inspection and Certification Systems (CCFICS) defines a vTPA program as “a non-governmental or autonomous scheme comprising the ownership of a standard that utilizes national/international requirements; a governance structure for certification and enforcement, and in which food business operator (FBO) participation is voluntary.”5 In other words, vTPA programs are formal and documented food safety and quality management systems developed and implemented by the private sector. A wide range of such programs exist from national industry association-owned schemes like the UK’s “Red Tractor,” to international programs like the British retail Consortium Global Standard for Food Safety, GlobalG.A.P., Food Safety System Certification 22000 (FSSC 22000), or the International Food Standard.

“Around the world, some public and private sector stakeholders have for many years now been working in partnership to strengthen food safety outcomes.”

Drivers, Benefits, and Challenges of Public-Private Collaboration on Regulatory Practices

Food business operators can use vTPA programs to drive improved hygiene practices, which strengthen consumer health protection, as well as opportunities for producers in developing countries to access new markets.6

The CCFICS has identified the potential for regulatory authorities to make use of reliable data generated by vTPA programs to optimize enforcement practices, where there is agreement among all the parties involved on the scope and process of data sharing, as well as an enabling legal framework. This approach may reduce the frequency of inspection visits to some food businesses, although it does not alter regulatory responsibility, which remains clearly with the national authorities. One major change, however, is the need for regulators to fully understand the vTPA programs used in their jurisdictions, including how the standards used in such schemes are based on international standards, notably Codex.

While some point to the potential benefits—increased efficiencies, better targeting of resources for inspection, reduced inspections for better-performing businesses, improved outcomes—of greater regulatory cooperation on food safety, others see concerns. These include possible conflict of interest, free-rider problems, loss of transparency, and/or unclear accountability. There also are fears that official encouragement or recognition of vTPA programs may diminish the national food control system and may exclude small-scale operators, particularly in developing countries.7 This reflects concerns expressed in the past by some World Trade Organization (WTO) members that private assurance schemes include standards that might be more rigorous than international standards (Codex), increasing the cost of compliance and negatively affecting the ability of developing countries to trade.

Over the last year or two, there appears to be more appetite emerging among some countries to understand the vTPA approach and how it might strengthen the national food control system. This is reflected in the development of Codex guidelines for the use of voluntary third-party assurance programs, expected to be adopted in 2021. The 25th Session of the Codex Committee on Food Import and Export Inspection and Certification Systems (CCFICS25), which was held virtually between May 31 and June 8, 2021, is where members were scheduled to vote on the adoption of this new guideline.

What Is Needed for Successful PPPs?

PPPs offer numerous benefits for food safety stakeholders; however, their establishment also can be a challenge in many countries. As a starting point, industry leaders and policymakers should sign up to a shared objective, in this case the safeness of food. When there is a lack of motivation to join forces, policymakers can be persuaded through the public health, social, and economic benefits, such as increased access to safe and nutritious food, including reduced foodborne illnesses, larger sales and industry tax revenues, and opportunities for private sector development and employment linked to new markets.

Even if stakeholders agree on shared food safety objectives, partnerships can fail, particularly when trust is shaky or a culture of cooperation is not firmly established. For this reason, an honest broker through an international development agency can often act as a facilitator to help get the partnership up and running, although this approach cannot be considered risk-free. To be sustainable, the partnership must be based on strong national demand and ownership. The international partner must have the technical competency and soft skills to understand and adapt to the local context, as well as to coach the local stakeholders so that the partnership grows and thrives from the bottom up.

Food Safety as a Multidisciplinary Domain

With regard to most complex partnerships, including coregulatory partnerships, additional prerequisites must be in place, like an effective national quality infrastructure system for integrity and sustainability. As long as countries lack internationally recognized certification, accreditation, or metrology services, food businesses will have to rely on external service providers from other countries, increasing their operational costs.

Governments and private sector stakeholders in many countries have invested billions of dollars and substantial time to develop robust food control and food safety management systems. In less-developed countries, public sector authorities responsible for food safety often lack the resources, competencies, infrastructure, and equipment for food control. There is scope for these governments to better leverage private initiatives, including vTPA programs, as part of an effort to invest more wisely in food safety and to make better decisions based on risk. Making the most of these opportunities will depend on increased investments in the services that are essential for a well-functioning food industry, including quality infrastructure.

Establishing and maintaining PPPs based on a coregulatory approach depends on trust, clarity of roles and responsibilities, and a continuous and open exchange of information across relevant competent authorities, including conformity assessment bodies, as well as the industry, vTPA service providers, and owners. Ideally, there is also a continuous, consent-based exchange of information among the actors involved, without threatening or overwriting the defined roles and responsibilities for food control.

“Interest in public-private sector collaboration is growing, as governments search for alternative and innovative solutions to enhance their food control system, and small and medium-size enterprises seek new markets in the high-value domestic retail sector, locally, regionally, and globally.”

Building Awareness and Knowledge on Best Practices

UNIDO is partnering with the STDF and others to share experiences and lessons from countries that are using the vTPA approach to strengthen food safety outcomes. For instance, on the occasion of World Accreditation Day on June 9, 2020, UNIDO and the STDF convened an online discussion on the role of accreditation in the introduction of a vTPA approach.8 Experts from the global food safety community, including food regulators and development practitioners, shared their views on how the vTPA approach could best be used in developing countries, with over 230 stakeholders from around the world. Key questions focused on the potential of vTPA approaches to help respond to the challenges posed by the global pandemic, the role of data, and how to foster trust across government and business.

UNIDO and the STDF also shared their experiences of vTPA programs during a thematic session on this topic on November 3, 2020, linked to the Fifth Review of the Operation and Implementation of the WTO Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) Measures.9 Addressing vTPA programs as part of national SPS control systems, the WTO SPS Committee event took a closer look at how some regulators have used—or plan to use—vTPA programs to promote risk-based approaches and complement their national SPS control systems. Attention focused on the experiences and potential of this approach, as well as some of the challenges and possible risks involved, with interventions from regulators benefiting from two new STDF regional projects to pilot and learn more about rolling out the vTPA approach in Central America and West Africa.

What Do We Know about Regulatory Frameworks and Practices on vTPA Programs in Food and Feed Safety?

To learn more about existing and/or planned regulatory frameworks and practices related to vTPA programs—including quality management systems, assurance schemes, or certification programs—in food and feed safety, the STDF and UNIDO teamed up with the Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture (IICA) to survey focal points in the Food and Agriculture Organization/World Health Organization (FAO/WHO) Codex Alimentarius Commission and WTO SPS Committee. The survey was carried out in 2020 and completed by 64 officials of competent authorities representing 47 countries—18 developed countries and 29 developing countries.

Regulators agreed on the benefits of cooperating with the private sector to support and not to diminish their roles and to multiply the results achieved by national food control systems (Figure 2). Over 75 percent of the survey respondents saw advantages of public-private cooperation, from improvements in food hygiene and safety to a more efficient allocation of resources and time for inspection, allowing official controls to focus on higher risks and opportunities to support improved compliance with national food safety regulations. These include an exchange of information between regulatory authorities and the third-party service entities (vTPA program owners and certification bodies) with the consent of food businesses.

But roughly half the respondents raised some concerns. These focused on possible additional financial costs for food operators, confidentiality and reliability of private assurance systems, regulatory capture, and duplication of existing laws and regulations. One respondent highlighted the risk that cooperation with vTPA programs may compromise the responsibility and accountability of the public sector for food/feed safety control, particularly in cases where food regulators lack core knowledge or competencies in their responsibilities.

The survey findings highlighted the great diversity of approaches and practices related to cooperation on vTPA programs. Factors that are encouraging governments to use the vTPA approach include regulatory and buyer requirements, internationally recognized quality infrastructure, and more legal and operational capability (including policies, strategies, legislation, and IT systems) to ensure data privacy and management. A scrolling story, and more detailed report summarizing the findings, is available online.10

FIGURE 2. Benefits of Partnerships Based on vTPA Programs

Diversity of vTPA Programs and Ways They Are Taken into Account

The survey found that information sharing between the parties most often occurs based on a formal arrangement, such as a contract or memorandum of understanding. However, in some countries, existing data privacy regulations hinder the sharing of information, making it impossible for certification bodies or vTPA program owners to share information on food safety compliance without the explicit agreement of business owners. In most cases, the reliability of the data generated by vTPA programs and the adequacy of practices in voluntary food safety audits are assessed and ensured through legal requirements and revision of vTPA governance structure and less by the competency of auditors working for private certification bodies.

How Can Advances in Data Help Transform Food Safety Decision-Making?

The World Economic Forum urges a more agile approach to regulation to unlock the potential of the “Fourth Industrial Revolution.” It calls for regulators to leverage the role that the private sector can play in the responsible governance of innovation, including making use of industry-led governance mechanisms, such as voluntary standards, codes of conduct, and industry schemes to help deliver policy objectives. Indeed, this has already been happening in food safety regulation in developed countries, with growing interest in how developing countries might benefit from this approach in the future.

New data-related technologies offer multiple opportunities to trigger transformational improvements in food safety processes and tasks led by government authorities as well as the private sector. The vTPA approach opens up additional options to use data to transform food safety regulatory decision-making and implement a risk-based approach. The pandemic has highlighted how data-driven regulatory decision-making—including data from vTPA programs—can provide valuable information to support national food control systems in prioritization of inspection visits.

The forthcoming Codex guidelines provide a framework and criteria to assess the integrity and credibility of the governance structure of vTPA program owners and the reliability of data and information generated by such programs to support national food control system objectives.

Recognizing this potential, some regulators are already collecting and using various types of food safety-related data—including data from food business operators and certification bodies—to improve their intelligence, direct scarce resources to areas of highest risk, and optimize food safety performance and results. This is possible only with access to reliable and quality data that ensures trust.

The vTPA approach underscores the need for data integrity through checks and balances based on a robust quality infrastructure system. Data gained through audit outcomes can improve the risk profiling of food sectors in terms of compliance with national regulatory requirements and identify or alert users to the need for potential interventions in the form of regulatory enforcement. This entails enhanced targeting and focus of inspectors on high-risk sectors, which in turn can result in better use of public resources.

Information on audit outcomes can be shared only with the consent of the relevant food businesses and vTPA program owners, which requires the negotiation of clear agreements, for instance, memoranda of understanding. In some countries, new legislation may be needed to increase reporting of noncompliant food businesses by certification bodies and vTPA owners.

“New data-related technologies offer multiple opportunities to trigger transformational improvements in food safety processes and tasks led by government authorities as well as the private sector.”

Piloting the vTPA Approach in West Africa and Central America

The vTPA approach is seen as an opportunity to promote a more agile, targeted, modernized, and risk-based approach to improve food safety outcomes. Some developing countries are keen to understand how they might use this approach to improve (not to replace or diminish) their national food control system and help small-scale food business operators improve their food safety management. But questions persist about how to do this in practice and how to address the risks.

Two ongoing STDF-funded regional projects in Central America and West Africa aim to answer these questions. By piloting the vTPA approach, in practice in selected sectors—including horticulture and aquaculture—the projects will test how competent authorities can cooperate more with the private sector to improve food safety outcomes.

Overall, the projects seek to drive up compliance with national food safety standards and regulations through better targeting of official resources to facilitate improved public health outcomes and trade opportunities. They will create new knowledge on how food safety regulatory authorities in low-income countries—where food regulatory decision-making practices are not well-developed—can use the vTPA approach to modernize and support a risk-based regulatory framework, based on Codex guidelines.

In countries participating in the pilot projects, the use of vTPA programs is still limited and mostly applied in the form of a few programs, like GlobalG.A.P., FSSC 22000, or British Retail Consortium. Consequently, incremental food safety capacity-building programs are essential for food businesses to meet national regulatory requirements and then product certification.

These regional projects encourage public-public and public-private collaboration at the national, regional, and global levels. Mentoring activities will link food safety regulators in Central America and West Africa to regulators in other countries already using the vTPA approach so they can benefit from their knowledge and experiences.11

Opportunities to Get Involved

UNIDO, in collaboration with the STDF and IICA, is launching a virtual partnership platform to leverage relevant expertise and resources from interested public and private sector organizations to support improved results under the vTPA regional projects. Expressions of support would be welcome from food safety scheme owners and certification providers, food safety consulting companies, the food industry, and most importantly regulators from other countries. Members of the platform will connect virtually to hear the latest updates about the project implementation and identify opportunities to engage.

Contact Gabor Molnar in UNIDO’s Sustainable Food Systems Division to find out more about the partnership platform and how you can participate.

About the STDF and UNIDO

The STDF is a global partnership to facilitate safe trade, contributing to sustainable economic growth, poverty reduction, and food security in support of the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals. The STDF promotes improved food safety and animal and plant health capacity in developing countries. This helps imports and exports meet SPS requirements for trade, based on the international standards recognized in the WTO SPS Agreement. The STDF brings together diverse stakeholders from across agriculture, health, trade, and development. Its founding partners are the FAO, OIE, World Bank Group, WHO, and WTO, including the Codex and International Plant Protection Convention Secretariats.

UNIDO is a specialized agency of the United Nations that assists countries in economic and industrial development. UNIDO serves as an honest broker between the public and private sectors through its technical assistance as well as normative functions, and focuses, inter alia, on creating sustainable agri-food businesses among its member states by developing public and private sector capacities and practices.

References

https://www.unido.org/sites/default/files/files/2020-02/UNIDO FSA_brochure_EN_FINAL.pdf.

For more details, see STDF's PPP briefing at www.standardsfacility.org/sites/default/files/STDF_Briefing_Note_15.pdf and the STDF/IDB PPP to enhance SPS capacity document at www.standardsfacility.org/public-private-partnerships.

To find out more about this partnership, which was facilitated by UNIDO under an STDF-funded project, see www.standardsfacility.org/PG-343.

http://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/news-and-events/news-details/en/c/1330660/.

Find out more and listen to the webinar at www.unido.org/news/partnering-improve-food-safety-outcomes-accreditation-and-role-vtpa-programmes.

Find out more and view the presentations at www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/sps_e/sps_thematic_session_31120_e.htm.

Find out more about the regional pilot project in Central America led by IICA with the public/private sector in Belize and Honduras (www.standardsfacility.org/PG-682) and the regional pilot project in West Africa, led by UNIDO with the public/private sector in Mali and Senegal (www.standardsfacility.org/PG-665).

Gabor Molnar is a development expert working in the Sustainable Food Systems Division of UNIDO, where he designs and implements food safety and agri-food value chain development projects.

Marlynne Hopper is deputy head of the STDF, where she leads STDF’s knowledge work on diverse topics related to facilitating safe trade, including PPPs.

The views expressed in this article are entirely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of their organizations or other affiliated partners.