Regulatory Report

By Brett Weed, M.P.H., M.S., Consumer Safety Officer, FDA CORE Network, Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN), U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA); Karunya Manikonda, M.P.H., Epidemiologist, FDA CFSAN; Allison Wellman, M.P.H., Epidemiologist, FDA CORE Network; Greg Gharst, Ph.D., Interdisciplinary Scientist and Microbiologist, FDA Office of Food Safety; Matthew Doyle, D.V.M., M.P.H., Veterinary Medical Officer, FDA Office of Food Safety; Amanda Conrad, M.P.H., Epidemiologist, Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); Alexandra Palacios, M.P.H., Epidemiologist, DFWED, NCEZID, CDC; Melanie LaGrossa, M.P.H., Consumer Safety Officer, FDA CFSAN Office of Compliance; and Stelios Viazis, Ph.D., Consumer Safety Officer, FDA Core Network

Outbreaks of Foodborne Illnesses and Recalls Associated With Ice Cream and Frozen Dessert Products

Reports in the literature indicate that ice cream has been associated with illnesses linked to numerous pathogens, including Listeria, which can cause severe illness

Image credit: ASIFE/iStock/Getty Images Plus via Getty Images

SCROLL DOWN

People in the U.S. consume an average of 21.2 pounds of frozen dairy products annually, drawing from the 6.4 billion pounds of ice cream and frozen desserts produced per year.1,2 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) FoodNet Population Survey, approximately 53 percent of Americans consumed ice cream at least once in the past seven days.3 Unsurprisingly, production of ice cream peaks in the summer months, with June being the highest.4

Ice cream, as we use here, collectively represents commercial and homemade ice creams, frozen desserts, and novelties. Ice cream has been implicated in notable foodborne illness outbreaks prior to 2014, including an outbreak in 1994 that received extensive media coverage and was linked to a nationally distributed ice cream brand contaminated with Salmonella enteritidis.5 Between 3,000 and 5,000 cases of illness were reported, with 400 cases in 35 states confirmed by CDC. The source was identified when the outbreak strain of S. enteritidis was isolated from the implicated ice cream.6,7 Even earlier, an outbreak in 1940 of Staphylococcus aureus toxin poisoning linked to homemade vanilla ice cream is still used today as a case study in the training of new foodborne epidemiologists.8,9

Potential Points of Contamination

Reports in the literature indicate that ice cream has been associated with illnesses linked to numerous pathogens, including Salmonella, Escherichia coli O145/O26,10 norovirus,11 Staphylococcus aureus toxin,12 Bacillus cereus, and Shigella.13 Pathogen introduction into the product can occur at various points throughout the production process. Causes include inadequate pasteurization of milk and cream, in-process contamination due to sanitation lapses, introduction of contaminated ingredients (sometimes called inclusions in the dairy industry), or post-process contamination from insanitary plant environments or practices. Fortunately, proper food safety controls can significantly minimize the risk these pathogens pose to consumers.

Review of Listeria monocytogenes Outbreaks Linked to Ice Cream, 2014–2022

While each of the previously mentioned foodborne pathogens are potential hazards that ice cream manufacturers must be aware of and take steps to control, L. monocytogenes has emerged as the most recent and severe organism of concern. CDC estimates that approximately 1,600 cases of foodborne listeriosis occur annually in the U.S.,10 at an economic cost of just over $2 million per case, according to an analysis by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).11,12 Listeriosis is a serious illness that primarily affects pregnant people and their newborns, older adults, and people with weakened immune systems.13 Products linked to outbreaks of listeriosis often become adulterated due to environmental contamination present in the processing environment.14

L. monocytogenes was isolated from the processing equipment and environments of ice cream manufacturing plants as early as 1990, but no cases of listeriosis were linked to ice cream as of a 1999 report.15 The first outbreak of listeriosis linked to ice cream occurred in 2014 and was among patients in a single healthcare facility in the state of Washington. Patients were served milkshakes made at the facility with contaminated milkshake mix, which highlighted the risk of L. monocytogenes in frozen dessert products.16,17 The manufacturer that supplied the milkshake mix to the healthcare facility recalled nearly all production from the year leading up to the outbreak, at a direct cost of almost $1 million.18 Following the initial outbreak, a third illness was identified in a patient at the same facility. The facility had switched mix providers, but the milkshake machine was still contaminated with L. monocytogenes from the implicated mix.19

In the nine years since the 2014 outbreak, there have been four additional listeriosis outbreaks linked to ice cream products. A review of CDC's National Outbreak Reporting System identified five L. monocytogenes outbreaks between 2014 and 2023 linked to ice cream products. These outbreaks resulted in 46 illnesses, 41 hospitalizations, and four deaths. Until 2021, ill people included in outbreaks linked to ice cream products were primarily in institutional settings such as hospitals, long-term care facilities, and nursing homes.

As described extensively in our previous Food Safety Magazine articles,20,21,22 when foodborne illnesses occur, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) works closely with CDC and state and local partners to mitigate threats to public health and minimize the impact of future occurrences. This includes activities to alert consumers of contaminated products, promptly removing adulterated products from commerce, and preventing future occurrences. As a tool for identifying the source of bacteria that have made people ill, pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was once the primary bacterial subtyping method used in the U.S. for classifying pathogens according to their "DNA fingerprint."23,24 Now, investigators use an even more sensitive subtyping method called whole genome sequencing (WGS) as the standard bacterial subtyping method. If the fingerprint of a bacterial isolate from a patient and another bacterial sample isolated from a food product are genetically related, then it provides evidence about the source of the exposure to the foodborne pathogen. These laboratory techniques, combined with epidemiological data and product traceback, can be used together to identify the source of illnesses.

In 2015, the first multistate outbreak of listeriosis was linked to commercially produced ice cream, produced by an ice cream manufacturer that operated facilities in three states with headquarters in Texas. A total of ten ill people in four states (Arizona, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas) were identified. All ten people were hospitalized, and three deaths were reported.25,26 Illnesses spanned a total of five years, from 2010–2015. The outbreak strains of L. monocytogenes were identified in 2015 after routine product surveillance isolated the pathogen in retail packages of ice cream products, and the strains were genetically related to several recent human illnesses by PFGE.

“The 2015 ice cream outbreak was an early example of both sample-initiated retrospective outbreak investigation and the power of molecular methods to connect illnesses with a food source over a long period of time.”

The link between illnesses in the 2015 outbreak and the manufacturer's ice cream, first detected by PFGE, were subsequently confirmed via WGS. Multiple strains were identified among isolates from ice cream, production facilities, and ill people. Using the laboratory data as a clue for the source of illnesses, investigators reviewed ice cream exposures for ill people, sampled the manufacturing environment of the firms' three facilities, and completed additional product testing. These efforts identified L. monocytogenes in all three production facilities and in ice cream produced in two facilities. Investigation by FDA and state partners found a number of insanitary conditions in the manufacturer's three facilities, including condensate dripping onto food contact surfaces, equipment design that did not allow for adequate cleaning, and lapses in personnel sanitation practices.27,28,29 The manufacturer recalled all products made at its facilities. Ultimately, the outbreak led to a corporate guilty plea to federal criminal charges of distributing adulterated food products and a court-imposed monetary penalty of $17.25 million. This outbreak was an early example of both sample-initiated retrospective outbreak investigation and the power of molecular methods to connect illnesses with a food source over a long period of time.28 It also further established ice cream as a potential hazard to individuals susceptible to invasive listeriosis, even at extremely low contamination levels.30

A more recent example of L. monocytogenes as a food safety hazard in ice cream occurred in July 2022, when a multistate, travel-associated outbreak linked to an ice cream firm in Florida sickened 28 people in 11 states (Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Kansas, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Nebraska, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania), leading to 27 hospitalizations, one death, and one fetal loss.31 This was the first outbreak of listeriosis linked to ice cream that included ill people outside of institutional settings. This was also the first outbreak of listeriosis linked to ice cream that affected pregnant people and teenagers—of note, one teenager in the outbreak did not have any underlying conditions. Interviews were completed with ill people or their surrogates, and 23 of the 23 ill people interviewed reported eating ice cream prior to their illness. Twenty-one ill people reported eating ice cream in Florida prior to their illness, and 16 reported specifically ice cream from the manufacturer. Nine ill people consumed ice cream exposures at four retail establishments, each of which sold ice cream manufactured by a small local firm that provided ice cream to retail establishments within the state of Florida.

An investigation by the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services at the ice cream manufacturer recovered L. monocytogenes isolates in ten environmental swabs and 20 finished product samples.32 Environmental swabbing by the firm isolated L. monocytogenes on multiple equipment surfaces and in four finished product ice cream bins. WGS analysis of the isolates collected in the manufacturing facility during the investigation were highly related to the isolates from patients. The investigation also identified that the firm failed to develop and implement a written food safety plan, as required by regulation. The company conducted a recall of all ice cream products with expiration dates through June 30, 2022.

FDA Recall and Regulatory Actions, 2015–2022

A review of FDA recalls data from 2015–2022 found that 31 Class I recalls were initiated for pathogens in ice cream products; 25 recalls were due to a risk of L. monocytogenes in finished products. Two recalls were for Salmonella contamination and four were for hepatitis A virus. Additional ice cream recalls occurred during this timeframe for the presence of undeclared allergens, indicating additional opportunities to improve manufacturing controls and food safety programs in the frozen dessert industry. Ice cream products often have a long shelf life, and even after a recall, consumers may continue to be at risk because recalled products may still be in their freezers at home. With the availability of ice cream premixes increasing, manufacturers must also be aware of the hazards associated with incoming ingredients and raw materials, in addition to their responsibilities for avoiding contamination directly within their control.

FDA conducted a focused assignment for inspection and sampling of 89 ice cream manufacturers in 2016 and 2017, in part to determine the prevalence of L. monocytogenes and Salmonella in ice cream facility environments.33 L. monocytogenes was isolated from samples collected at 19 facilities (21 percent) and Salmonella in one (1 percent). The L. monocytogenes isolates recovered at one facility in Florida were linked to three human illnesses prior to 2016 and led to a product recall and the suspension of the implicated facility's food registration by FDA in 2018.

When FDA finds that a manufacturer has significantly violated FDA regulations, FDA notifies the manufacturer. This notification is often in the form of a warning letter. The warning letter identifies the violation, such as poor manufacturing practices, problems with claims for what a product can do, or incorrect directions for use. The letter also makes clear that the company must correct the problem and provides directions and a timeframe for the company to inform FDA of its plans for correction.

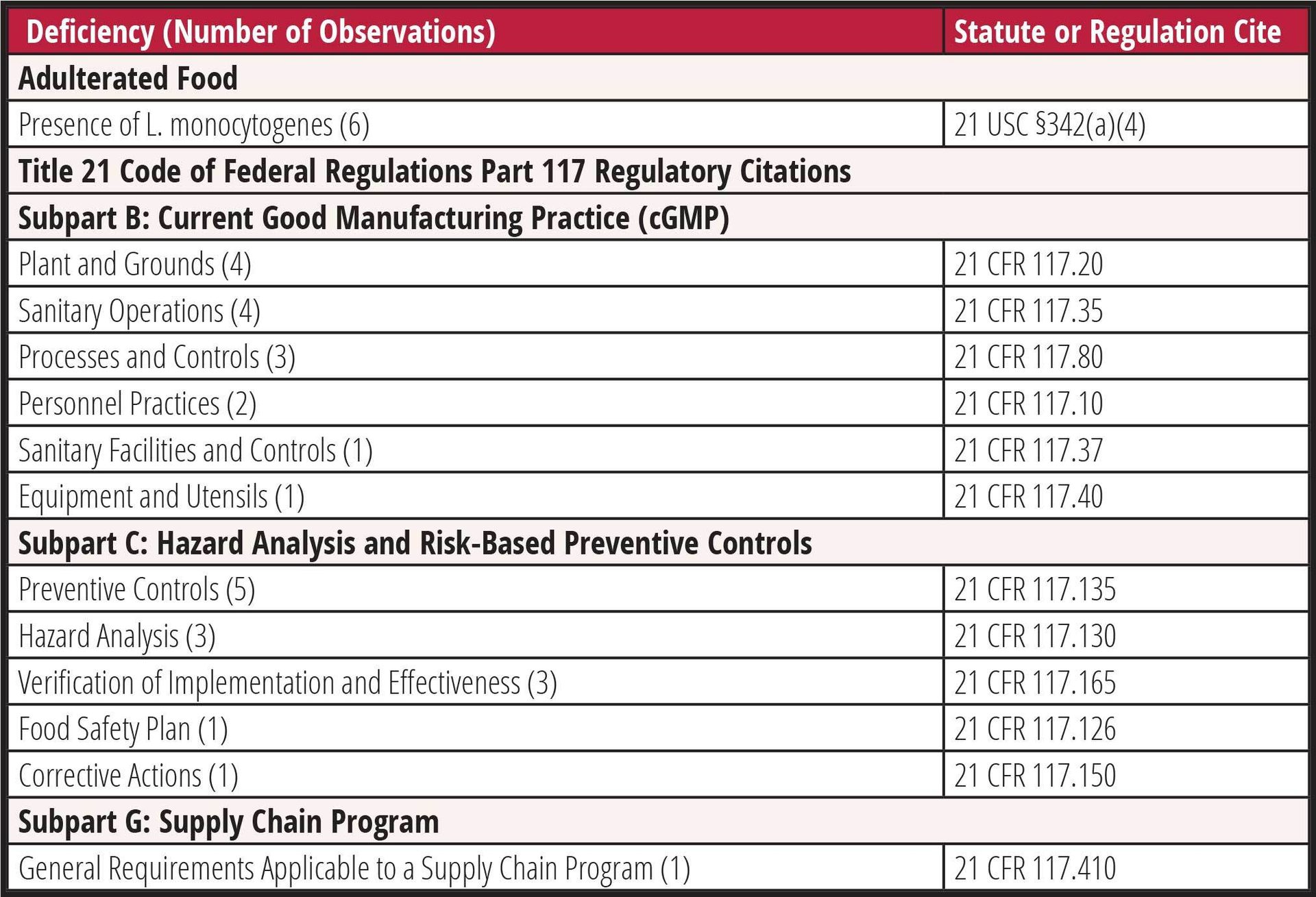

Since 2019, FDA has issued seven warning letters to ice cream manufacturers for insanitary conditions, food adulteration, or facility contamination with L. monocytogenes.32,34–39 Six of the seven facilities (86 percent) had L. monocytogenes isolated from the plant environment or finished product. The most frequent observations cited were deficiencies related to identification and implementation of preventive controls (five of seven; 71 percent), sanitary operations (four of seven; 57 percent), and equipment design or maintenance (four of seven; 57 percent). A complete summary of the observations cited in these warning letters is included in Table 1.

TABLE 1. Food Safety Deficiencies Cited in Ice Cream Manufacturer Warning Letters, 2019–2022

Requirements and Regulatory Compliance for Ice Cream Manufacturers

Frozen dessert manufacturers must, in general, comply with the current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP), hazard analysis, and FDA's Risk-Based Preventive Controls for Human Food rule (21 CFR 117). Certain small and very small firms may have modified requirements.40 CGMPs are codified in Subpart B of 21 CFR 117 and include requirements to ensure the safe production, handling, and distribution of food products. These elements include employee hygienic practices, facility sanitary operations, sanitary plant design and construction, and process controls. As noted in Table 1, cGMP deficiencies are frequently found in facilities where L. monocytogenes has been recovered during sampling. Since Listeria are often introduced into food from the plant environment, proper sanitary design and practices are essential in eliminating or reducing the risk of contamination.

Unless an exemption applies, manufacturers must develop and implement a food safety plan that minimizes the likelihood of foodborne illness or injury.41 The food safety plan must identify known or reasonably foreseeable safety hazards for the product and processes used in the facility. While this article is focused exclusively on microbiological hazards, it is important to note that the plan must address potential chemical and physical hazards, as well.

Food safety plans have seven required elements per 21 CFR 117.126:

- A written hazard analysis

- Preventive controls for identified hazards

- A supply chain program

- A recall plan

- Preventive controls implementation monitoring procedures

- Corrective action procedures

- Verification procedures.

For ice cream products, environmental monitoring for L. monocytogenes should be conducted as part of a broader preventive controls verification program. If pathogens are found in finished product or the plant environment, then the food safety plan and its controls should be re-evaluated, and corrective actions taken.

Food Safety Resources for Ice Cream Manufacturers

FDA has a variety of resources to support regulated industry in producing safe, wholesome food, some of which have been highlighted for producers of other dairy food products.20 For firms that are required to have a food safety plan, FDA has made available a software package that can assist firm managers in developing a plan specific to the needs of their operation.42 FDA also offers compliance guides and assistance to small businesses that seek help from the agency.43,44

FDA has published draft guidance on the control of L. monocytogenes in food processing environments, which includes recommendations on facility design, personnel practices, and sanitation procedures to control the risk of contamination.14 The draft guidance, when finalized, will represent the current thinking of FDA on this topic. Links to these tools and resources are provided in Table 2 for convenience. Facility owners and operators can also make use of the FDA Technical Assistance Network, a group of subject matter experts within the agency available to answer questions on the Preventive Controls for Human Food rule and implementation strategies.45

TABLE 2. Selected FDA and CDC Digital Resources

In addition to the resources provided by FDA, many university-based cooperative extension programs and industry sources can provide training and assistance. While neither FDA nor CDC can endorse a particular provider of third-party training or consulting, there are a variety of resources from academic and industry experts available to a facility operator. Several universities offer seminars, self-paced training courses, individualized consulting, and coaching for small- and medium-sized dairy businesses.46,47,48 Topics available at no or low cost include sanitation program design, recall plan development, ice cream production, marketing, and more. Previous reports in the published literature include catalogs of resources available to dairy businesses from universities and private consultants, including online training, in-person seminars, hands-on education, and consultation services.49

Dairy food trade associations also offer training to encourage the safe production of ice cream, including training courses and reference materials. State departments of agriculture, regional and local industry organizations, and dairy cooperatives may also be sources of expertise. Ice cream manufacturers are encouraged to contact their state and local regulators to identify the most appropriate training resources for their jurisdictions. It is ultimately the responsibility of the manufacturer to ensure that its products comply with applicable regulations and are safe for consumers.

“Each step in the 'rings of defense' must be used consciously and with proper consideration, as it may be obvious what caused the noncompliance, and its resolution may be straightforward, simple, and not costly.”

Conclusion

Collectively, recent outbreaks, recalls, and sample findings suggest a need for increased vigilance against microbial contamination, particularly L. monocytogenes, in frozen dessert products. Compliance with existing food safety regulations, as a part of a carefully designed and implemented food safety program, can reduce the risk of contamination. Preventing contamination of ice cream products is a legal requirement for manufacturers, a sound business practice, and most importantly, necessary to protect public health.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions of this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC).

References

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Economic Research Service (ERS). "U.S. production of ice cream and frozen yogurt totals 6.4 billion pounds per year." September 27, 2019. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/chart-gallery/gallery/chart-detail/?chartId=95003.

- USDA ERS. "Here's the scoop: U.S. residents consumed less ice cream in 2020 than in 2000." July 12, 2022. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/chart-gallery/gallery/chart-detail/?chartId=104203.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). "FoodNet FAST: Population Survey." 2022.

- Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. "Industrial Production: Manufacturing: Non-Durable Goods: Ice Cream and Frozen Dessert (NAICS = 31152)." Board of Governors of the Federal Reseve System. 2023.

- Minnesota Department of Health et al. "Emerging Infectious Diseases Outbreak of Salmonella enteritidis Associated with Nationally Distributed Ice Cream Products—Minnesota, South Dakota, and Wisconsin, 1994." Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 43, no. 40 (1994): 740–741.

- Hennessy, T.W. et al. "A national outbreak of Salmonella enteritidis infections from ice cream." New England Journal of Medicine 334, no. 20 (1996): 1281–1286.

- Schwartz, J. "Truck Linked to Ice Cream Poisoning." Washington Post. 1994.

- Gross, M. "Oswego County Revisited." Public Health Reports 91, no. 2 (1976): 168–170.

- CDC. "Oswego—An Outbreak of Gastrointestinal Illness Following a Church Supper." Atlanta, Georgia, 2003.

- Scallan, E. et al. "Foodborne illness acquired in the United States—Major pathogens." Emerging Infectious Diseases 17, no. 1 (2011): 7–15.

- Hoffman, S., B. Maculloch, and M. Batz. "Economic Burden of Major Foodborne Illnesses Acquired in the United States." USDA ERS, Ed. 2015.

- USDA ERS. "Cost Estimates of Foodborne Illnesses." Last updated March 2, 2023. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/cost-estimates-of-foodborne-illnesses.aspx.

- CDC. "Listeria (Listeriosis)." Last reviewed February 6, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/listeria/index.html.

- FDA Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN). Draft Guidance for Industry: Control of Listeria monocytogenes in Ready-To-Eat Foods. January 2017. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/draft-guidance-industry-control-listeria-monocytogenes-ready-eat-foods.

- Miettinen, M.K., K.J. Björkroth, and H.J. Korkeala. "Characterization of Listeria monocytogenes from an ice cream plant by serotyping and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis." International Journal of Food Microbiology 46, no. 3 (1999): 187–192.

- Rietberg, K. et al., "Outbreak of Listeria monocytogenes infections linked to a pasteurized ice cream product served to hospitalized patients." Epidemiology and Infection 144, no. 13 (2016): 2728–2731.

- Aleccia, J. "Ice creamery linked to Listeria failed earlier health inspection." Seattle Times. Seattle, Washington. 2014.

- Beecher, C. "Lesson From WA Ice Cream Recall: Don't Let it Happen to You." January 30, 2015. https://www.foodsafetynews.com/2015/01/dont-let-a-recall-happen-to-you-warns-owner-of-ice-cream-company/#:~:text=On%20Dec.,1%2C%202014%2C%20until%20Dec.

- Mazengia, E. et al. "Hospital-acquired listeriosis linked to a persistently contaminated milkshake machine." Epidemiology and Infection 145, no. 5 (2017): 857–863.

- Pereira, E. et al. "Recent Outbreaks of Listeriosis Linked to Fresh, Soft Queso Fresco-Type Cheeses in the U.S." Food Safety Magazine February/March 2023. https://www.food-safety.com/articles/8332-recent-outbreaks-of-listeriosis-linked-to-fresh-soft-queso-fresco-type-cheeses-in-the-us.

- Viazis, S. et al. "The Incident Command System and Foodborne Illness Outbreak Investigations." Food Safety Magazine October/November 2022. https://www.food-safety.com/articles/8048-the-incident-command-system-and-foodborne-illness-outbreak-investigations.

- Viazis, S., M. Bazaco, and D. Karas. "Regulatory Report: Outbreak Investigations of Foodborne Illnesses Linked to Atypical Food-Pathogen Pairs." Food Safety Magazine. January 14, 2021. https://www.food-safety.com/articles/1756-regulatory-report-outbreak-investigations-of-foodborne-illnesses-linked-to-atypical-food-pathogen-pairs.

- CDC. "Pulsed-field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE)." https://www.cdc.gov/pulsenet/pdf/PFGE_process_Infographic-H.pdf.

- Jackson, B.R. et al. "Implementation of Nationwide Real-time Whole-genome Sequencing to Enhance Listeriosis Outbreak Detection and Investigation." Clinical Infectious Diseases 63, no. 3 (2016): 380–386.

- CDC. "Multistate Outbreak of Listeriosis Linked to Blue Bell Creameries Products (Final Update)." June 10, 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/listeria/outbreaks/ice-cream-03-15/index.html.

- Conrad, A.R. et al. "Listeria monocytogenes Illness and Deaths Associated With Ongoing Contamination of a Multi-Regional Brand of Ice Cream Products, United States, 2010–2015." Clinical Infectious Diseases 76, no. 1 (2023): 89–95.

- FDA. "Blue Bell Creameries, LP, Broken Arrow, OK 483." Issued April 23, 2015.

- FDA. "Blue Bell Creameries Inc, Sylacauga, AL 483." Issued April 30, 2015.

- FDA. "Blue Bell Creameries, L.P. Brenham, TX, 483." Issued May 1, 2015.

- Chen, Y. et al. "Comparative evaluation of direct plating and most probable number for enumeration of low levels of Listeria monocytogenes in naturally contaminated ice cream products." International Journal of Food Microbiology 241 (2017): 15–22.

- FDA. "Outbreak Investigation of Listeria monocytogenes: Ice Cream (July 2022)." Content current as of January 25, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/food/outbreaks-foodborne-illness/outbreak-investigation-listeria-monocytogenes-ice-cream-july-2022.

- FDA. "Warning Letter: Big Olaf Creamery LLC dba Big Olaf." December 9, 2022 https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/big-olaf-creamery-llc-dba-big-olaf-642758-12092022.

- FDA. "Inspection and Environmental Sampling of Ice Cream Production Facilities for Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella FY 2016–17." Content current as of February 25, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/food/sampling-protect-food-supply/inspection-and-environmental-sampling-ice-cream-production-facilities-listeria-monocytogenes-and.

- FDA. "Warning Letter: The Royal Ice Cream Company Inc." July 28, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/royal-ice-cream-company-inc-630433-07282022.

- FDA. "Warning Letter: Greenwood Ice Cream, LLC." December 17, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/greenwood-ice-cream-llc-616395-12172021.

- FDA. "Warning Letter: Velvet Ice Cream Company." May 6, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/velvet-ice-cream-company-575444-05062019.

- FDA. "Warning Letter: Friendly's Manufacturing and Retail LLC." November 22, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/friendlys-manufacturing-and-retail-llc-590821-11222019.

- FDA. "Warning Letter: Sassy Cow Creamery, LLC." December 4, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/sassy-cow-creamery-llc-587954-12042019.

- FDA. "Warning Letter: Ramar International Corporation." October 13, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/ramar-international-corporation-608782-10132020.

- FDA. "Small Business Under the PC Human Food Rule." https://www.fda.gov/media/117785/download.

- FDA. Draft Guidance for Industry: Hazard Analysis and Risk-Based Preventive Controls for Human Food. Current as of January 2024. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/draft-guidance-industry-hazard-analysis-and-risk-based-preventive-controls-human-food.

- FDA. "Food Safety Plan Builder." Content current as of April 8, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/food/food-safety-modernization-act-fsma/food-safety-plan-builder.

- FDA. "Small Business Assistance." Content current as of September 28, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/industry/small-business-assistance.

- FDA. Small Entity Compliance Guide: What You Need to Know About Current Good Manufacturing Practice, Hazard Analysis, and Risk-Based Preventive Controls for Human Food. November 2016. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/small-entity-compliance-guide-what-you-need-know-about-current-good-manufacturing-practice-hazard.

- FDA. "FSMA Technical Assistance Network (TAN)." Content current as of March 14, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/food/food-safety-modernization-act-fsma/fsma-technical-assistance-network-tan.

- Cornell University. "Artisan Dairy Food Safety Coaching." 2024. https://cals.cornell.edu/education/degrees-programs/artisan-dairy-food-safety-coaching.

- University of Wisconsin-Madison. "Dairy Foods Short Courses." 2024. https://dairyfoods.wisc.edu/.

- Pennsylvania State University. "Dairy Food Processing." 2024. https://extension.psu.edu/food-safety-and-quality/dairy-food-processing.

- Biango-Daniels, M.N. and B.E. Wolfe. "American artisan cheese quality and spoilage: A survey of cheesemakers' concerns and needs." Journal of Dairy Science 104, no. 5 (2021): 6283–6294.

Brett Weed, M.P.H., M.S., is a Consumer Safety Officer at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) CORE Network in the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN).

Karunya Manikonda, M.P.H., is an Epidemiologist with FDA CFSN.

Allison Wellman, M.P.H., is an Epidemiologist with the FDA CORE Network.

Greg Gharst, Ph.D., is an Interdisciplinary Scientist and Microbiologist with the FDA Office of Food Safety.

Matthew Doyle, D.V.M., M.P.H., is a Veterinary Medical Officer with the FDA Office of Food Safety.

Amanda Conrad, M.P.H., is an Epidemiologist with the Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Alexandra Palacios, M.P.H., is an Epidemiologist in the DFWED at the NCEZID at CDC.

Melanie LaGrossa, M.P.H., is a Consumer Safety Officer with the FDA CFSAN Office of Compliance.

Stelios Viazis, Ph.D., is a Consumer Safety Officer with the FDA Core Network.