AUDITING

By Cori Muse, Food Safety and Regulatory Consultant and Owner, Muse Food Safety Solutions LLC

Beyond the Score: Risk-Focused Audits and the Ethics of Prevention

An urgent call to rethink food safety auditing from the ground up

Image credit: LiudmylaSupynska/iStock/Getty Images Plus via Getty Images

SCROLL DOWN

Despite the near-universal adoption of Global Food Safety Initiative1 (GFSI)-aligned audits across the entire global food industry, we are still watching people get sick, companies go bankrupt, and public trust disintegrate, often all in the same news cycle. The industry has fallen into a dangerous rhythm of performative compliance, where box-checking masquerades as risk management and standardized protocols are applied like a bandage over deeply individualized wounds. Hazards that are statistically improbable or operationally irrelevant still eat up hours of documentation and auditor scrutiny, while the real threats—the ones that result in consumer's long-term health problems and/or kill people—slip through the cracks.

I have spent decades auditing facilities and watching systems built for safety morph into systems built for optics. The latter type of system is driven more by marketing and sales teams and certification bodies than by microbiologists and competent frontline operators, who should possess the relevant knowledge and experience to make proper disposition on food product(s) and their relevant, associated hazards.

Worse still, many of these companies have already baked failure into their business models, budgeting for recalls, consumer settlements, and leaning on insurance policies that shield their bottom line from meaningful impact. In other words, not only can they afford the consequences of making people sick—they operate as though those consequences are simply the cost of doing business. Furthermore, in the e-commerce space, arbitration clauses buried in the "fine print" of meal kit subscriptions and direct-to-consumer (DTC) food services quietly strip consumers of their right to sue. Unlike buying from a grocery store, where the manufacturer can be held accountable, ordering food by mail often means that the consumer signs away their legal recourse when they agree to the e-commerce company's "terms and conditions." The Daily Harvest outbreak in 20222 is a sobering example. Hundreds fell ill, but legal action was stifled by pre-signed arbitration agreements buried in online terms and conditions. This is how regulatory gaps in e-commerce are exploited—not to enhance safety, but to shield corporations from liability while leaving consumers vulnerable.

The result? Recalls are climbing, outbreaks are becoming harder to trace, and preventable deaths are being shrugged off as collateral damage. At the time of writing this article, of the 25 illness outbreaks reported to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2024, six went "unidentified" after the investigation was closed. In 2025, for closed investigations, there have been two major outbreaks, and one has already been closed as "unidentified," while three of the four open investigations are currently "not identified."3

This article is an urgent call to rethink food safety auditing from the ground up: tailor it, ground it in science, and above all, make it ruthlessly risk-based. Context is key in any situation, but especially in food safety. Time and attention wasted on managing risks that are not applicable to your operation puts your consumer at risk. It diverts attention and resources and is futile, but it is a requirement to obtain the paper certificate from GFSI.

“Too often, 'audit ready' is marketed as a quick fix—something sold by certain certification bodies or consultants as a checklist-driven solution.”

Desired Goals

The real question—and the one that separates ethical operators from opportunistic ones—is: What is the actual desired goal of your food business? Is the aim simply to score well on an audit? Or is it to identify real risks, resolve issues at their root, and prevent them from happening again? Are you striving for true system efficacy and effectiveness, or are you just checking boxes to satisfy customer requirements and pass your next GFSI audit?

In my experience, when companies use phrases like "audit ready" and begin reaching out to experts or consultants a few months before their scheduled audit, it often signals a reactive mindset—not a commitment to building a strong, effective system. The focus, unfortunately, tends to be on passing the audit, obtaining the certificate, sending it to the customer, and then shelving the effort until the next cycle.

Too often, "audit ready" is marketed as a quick fix—something sold by certain certification bodies or consultants as a checklist-driven solution. These "quick fixes" are not about improving system efficacy or ensuring long-term safety—they're about optics. In these cases, consultants are not brought in to help build robust systems; they are brought in to make sure the audit day goes smoothly. Once the certificate is secured, it's back to business as usual—which, in these cases, was never truly "audit ready" to begin with.

The Problem With Generic Standards

GFSI-aligned standards were intended to be comprehensive; yet, in their ambition to apply everywhere, they fail almost everywhere. A universal checklist cannot possibly capture the nuanced, product- and process-specific risks that differ from one facility to the next. Yet, this one-size-fits-all model dominates the industry, pulling focus away from actual hazards. I have audited sites obsessed with flawless documentation while glaring operational threats—failing cold chains, roof leaks over exposed product, rampant mold, rodent infestations, etc.—go unaddressed or ignored.

GFSI's original mission was noble: to create a global blueprint for food safety management. In my opinion, what started as a framework has mutated into a profit-driven machine that is more interested in optics than outcomes. Today, the system is riddled with standards not grounded in science or real risk, and is enforced by auditors who often lack a basic background in microbiology, food science, or process engineering.

This system is clearly not working. Look no further than the outbreak track records of brands the public trusts—Dole, Abbott Nutrition, Nestlé, McDonald's, Taylor Farms, Blue Bell Ice Cream, Boar's Head, Bruce Pac, Daily Harvest, HelloFresh. These are industry leaders, not fringe players. Yet, these companies have been directly implicated in serious, sometimes fatal, foodborne illness outbreaks. The system isn't keeping consumers safe—it's allowing failure to occur under the guise of compliance.

Lessons From Tragedy

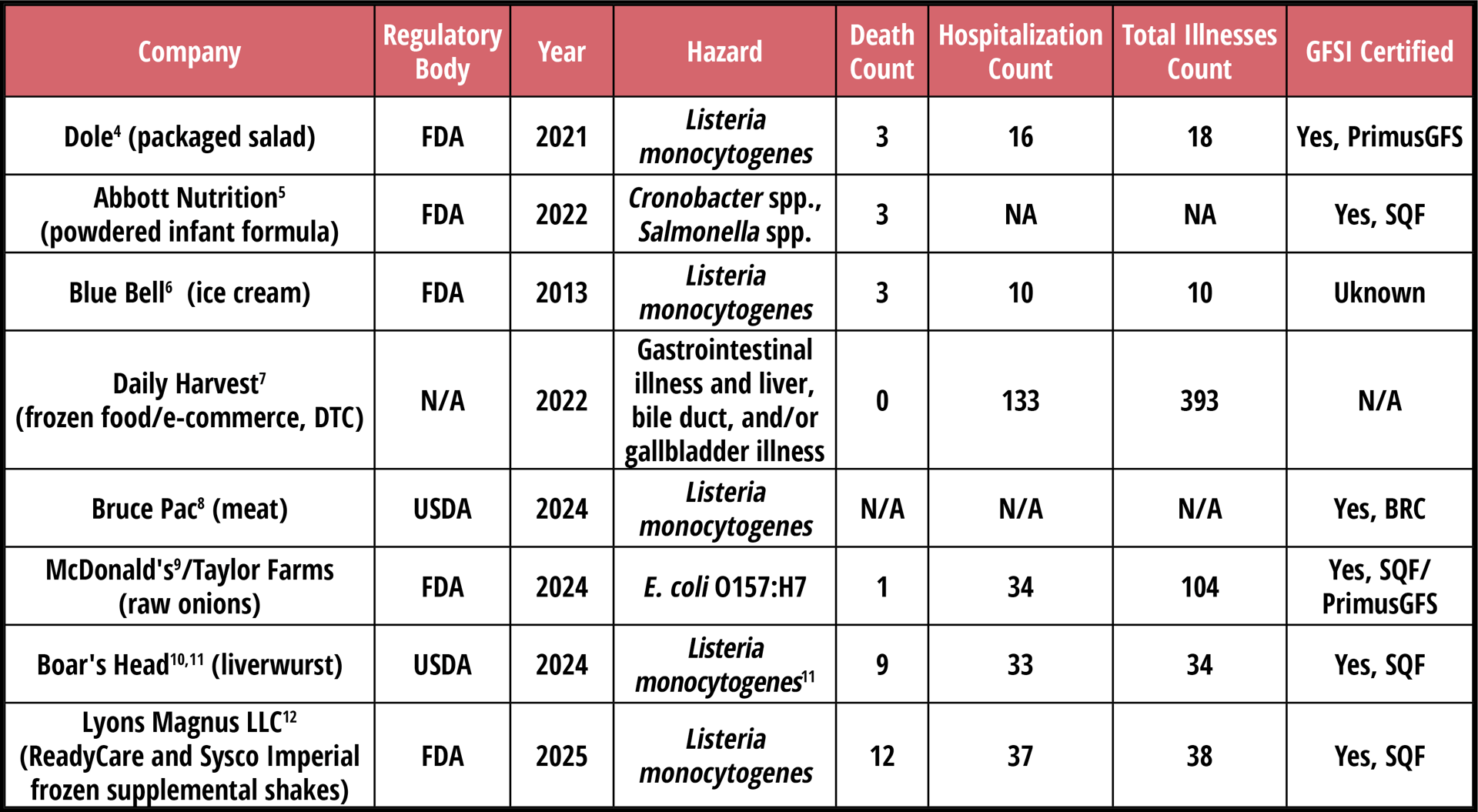

Table 1 takes a closer look at some of the recent, high-profile outbreaks that reveal problems with the system. These companies were inspected by their corresponding regulatory bodies, as well as by third-party auditors. In most cases, these companies had acceptable (if not exemplary) GFSI audit scores.

TABLE 1. Trusted Brands, Deadly Failures—Recent Foodborne Illness Outbreaks

These companies had voluntary certifications, met customer requirements, and passed internal, external, and regulatory audits—and yet, people died. Where was the system? Where were the auditors, the regulators, and the second-party customer inspections? How did so many layers of oversight fail to catch the obvious? The truth is unsettling: either audits are being done ineffectively—or the entire system is broken. I believe it's the latter.

To address this, we must move beyond isolated fixes and adopt a systems-thinking approach. As articulated in Polymathic Being,13 systems thinking teaches us that "problems never exist in isolation—they are components of larger, interdependent systems." When we treat failures as one-offs, we ignore the complex feedback loops, incentives, and blind spots that allowed them to occur in the first place.

We can't just tighten the procedure or revise the checklist. We must carefully evaluate the entire ecosystem of food safety—regulators, auditors, certification schemes, corporate incentives, and consumer trust—as a living system that either reinforces safety or permits failure. Only by understanding the interconnectedness of these elements can we design audits and oversight mechanisms that actually protect the public.

We, as scientists and professionals, have a duty far beyond checking boxes. Our expertise isn't just a job qualification; it's public trust. Most people do not have the knowledge or training that we possess. That makes our ethical obligation clear: to protect the public, even when it's uncomfortable, inconvenient, or unpopular.

If you're skilled, experienced, and capable of identifying risks, then you have a duty to act, speak out, and push for change. That includes lobbying your government, challenging broken systems, and demanding audits that are risk-focused, not performative.

It's time to stop pretending the current system is effective. It isn't—and every competent professional knows that. We must abandon the complacency of phrases like "this is how we've always done it" or "no one has complained before," as if the absence of reported problems somehow proves the system is sound. Silence is not validation. It's often a warning sign that we've chosen to ignore.

The question is: What are you going to do about it?

“That's the essence of risk-focused auditing—it requires constant recalibration throughout the process. If an audit is a snapshot in time, then use your sharpest lens.”

The Case for Risk-Focused Auditing

Risk-focused auditing is a pragmatic, targeted approach. It focuses on the most likely and most dangerous failure points in a system. This means investing quality time in carefully understanding the process, product, regulatory expectations, and operational context—well before the audit begins. A desktop review of prior audits, internal reports, and regulatory data allows auditors to triage areas into low-, medium-, and high-risk, focusing their limited time and energy where it matters most.

The same disciplined approach should apply during the audit itself. Never assume the previous auditor was either competent or thorough. You are entering with your own expertise and your own risk lens, not theirs. While you may choose to verify their findings, your focus should always remain on the current risks you've identified. That's the essence of risk-focused auditing—it requires constant recalibration throughout the process. If an audit is a snapshot in time, then use your sharpest lens.

Auditors who rely on "copy-paste" findings or piggyback on prior reports do a disservice to both the operation and the consumer. Often, this behavior is rooted in fear of scrutiny from the certifying body (CB), fear of contradicting prior audits, and fear of the internal conflict these scenarios may ignite. Program managers, who must answer to the accreditation body (ANAB), often discourage inconsistency—even when it is the result of a more accurate, present-day assessment. Auditors are frequently pressured to soften findings, reword nonconformities, or remove them entirely—not because the issues don't exist, but because the truth creates administrative tension. The result is "sanitized" audits that protect reputations but fail the public. So, the real questions then are: Will you choose integrity, knowing the pressure you'll face? Or will you conform, stay quiet, and risk being remembered as the auditor whose silence contributed to the next preventable, deadly outbreak?

Risk-focused auditing is not a new concept; it is just notoriously difficult to implement. It demands highly competent auditors and leaders with uncompromising integrity. It requires executives who are willing to look their shareholders in the eye and say, "We're prioritizing safety over profit." Take the Abbott Nutrition infant formula crisis, for example. This concerned a massively profitable company that had been warned. A whistleblower went to federal authorities and submitted a 34-page, detailed whistleblower report14 that went ignored until several infants died. The government and company employees knew; yet, formula was still shipped to an at-risk consumer group. The adulterated formula sickened numerous infants and led to at least three confirmed deaths.

What followed was a political blame game, but the author's opinion is that the root cause of the shortage wasn't the political administration; it was an ongoing, long-term failure in food safety oversight. The notion that fast-tracking formula from foreign suppliers would somehow fix the issue is absurd. If companies that have already received government authorization cannot operate ethically, legally, or safely, then why would we place trust in imports from manufacturers we have never inspected? The Abbott case didn't just expose the cracks—it blew the doors off the illusion that "compliance equals safety."

“If done right, these internal systems should be so robust that external regulators serve only to verify effectiveness, not to expose failures.”

The Call to Action: Reclaiming the Audit

The most powerful audits are not the ones performed for paper certificates—they are the ones done internally. Internal audits, when designed around actual risk and regulatory needs, create a feedback loop that keeps systems strong every day—not just on audit day. Internal auditing allows organizations to be proactive, not reactive. If done right, these internal systems should be so robust that external regulators serve only to verify effectiveness, not to expose failures.

Internal Audits: The Most Important Tool You Have

The most effective audit you will ever conduct is an internal one. Why? Because you already have everything you need: data, tools, people, and process knowledge. And yet, many companies miss the mark. They hand over internal audit design to executives or corporate officers who have never stepped foot onto the production floor. Often, the result is that audit programs are built around certification schemes and customer expectations, but not real operational risk.

If your internal audit program is not identifying the root causes of recurring issues—such as consumer complaints, contamination events, or product recalls—then it isn't an audit at all; it's a performance. You're not measuring system effectiveness; you're staging compliance theater.

Furthermore, if your corporate team is responsible for designing those audits but is not physically present onsite, in the facility, or on the floor—at least quarterly—then they are not qualified to lead or participate in the process. Internal audits must be developed and executed by those who understand the daily realities of the operation. The responsibility belongs to the site. Corporate's role is to support and review, not to dictate from a distance.

Corporate leaders who fail to set foot in their facilities aren't just ineffective—they're grossly negligent.

"Audit Ready" Isn't a Standard—It's a Marketing Phrase

The term "audit ready" is meaningless without substance. I have opened environmental monitoring programs in facilities producing deli meat and found no mention of Listeria monocytogenes. I've seen dairy operations label their hazard as simply "contamination," with no specific pathogens identified. If you're not identifying the specific risks in your process, then you're not controlling them—and if you're not controlling them, then you're leaving people vulnerable.

Every Audit Must Be Risk-Focused

Every element of your audit must be rooted in actual risk—not convenience or certification trends. Rooted in actual risk means:

- Defining specific hazards for your products and processes—not generalities

- Evaluating facility age, infrastructure, and ownership, because repair timelines matter

- Testing your water, air, and environment at relevant intervals—not just relying on outdated municipal reports

- Auditing based on data trends, complaint logs, sanitation records, equipment downtime, utility failures, and other information.

Nothing in a food production facility happens in a vacuum. A clogged drain, a dip in water pressure, a faulty metal detector—every minor failure has the potential to cascade. Internal audits must capture these moments before they become headlines, and facilities must adopt a systems-thinking approach to be effective in their endeavors.

Design Your Internal Audit to Uncover the Truth

If your CAPA (corrective and preventive actions) log is empty, you're either running the best operation in the industry or you're lying to yourself. No facility is perfect. There is no shame in identifying failures—only in pretending they don't exist.

A strong internal audit will:

- Challenge assumptions

- Disrupt complacency

- Train your team to think critically—not just comply

- Above all, uncover problems you didn't know you had.

You must also train your internal auditors. Rotate assignments. Never allow quality assurance to audit itself. And never set your goal as "passing the audit." Your goal should be system effectiveness. Your audit should answer: Is our food safe? Is our system working? If not—where, why, and how do we fix it?

“When internal audits are designed correctly, regulators… should be able to review your internal system and find clear, documented evidence that your operation is functioning safely.”

A Moral Obligation

Experienced, intelligent professionals in the food industry have a responsibility and a moral obligation to use their knowledge and skillset to protect the public. Most consumers will never understand the risks we manage daily. That's not their job—it's ours. That duty includes setting up internal audits that are more robust than GFSI schemes, more rigorous than customer requirements, and more effective than any third-party "snapshot in time" inspection.

When internal audits are designed correctly, regulators should not have to dig for days to uncover major failures. They should be able to review your internal system and find clear, documented evidence that your operation is functioning safely. You should have data that proves it—not just because you're being audited, but because it's the right thing to do.

What Success Actually Looks Like

If a food facility claims to have gone a year with no nonconformances, this makes me suspicious. Are you telling me that not a single person failed to wash their hands? That you've never lost water pressure or temperature? That your metal detector never went down? In nearly two decades of auditing, I have never walked into a facility that didn't have something to improve. And that's okay—if you're willing to see it, fix it, and prevent it.

Ethical food safety isn't about being flawless. It's about being honest, vigilant, and relentless in your pursuit of improvement. You don't need a certificate to do this right. You need courage, competence, and commitment. Food safety isn't a marketing strategy; it's public trust. If you're not willing to confront your own system's weaknesses before someone else does, ask yourself: Why are you in this business?

Where We Go From Here

Auditing is not about checklists or binders. It's about people. It's about whether the food we put on shelves, send to hospitals, serve in schools, and feed to our families is truly safe. When lives are on the line, there is no room for complacency, performative actions, or false assurances.

If we want different outcomes—fewer recalls, fewer illnesses, fewer tragedies—then we must change the system. That change starts with internal audits designed around real risk, not recycled templates. It means empowering those on the ground to lead, not deferring to distant executives who have never walked the floor. It requires hiring auditors with technical expertise, operational awareness, and the courage to speak the truth.

We must reject audits done for optics, and demand audits done for risk-focused, desired outcomes. The tools are already in our hands. We know what effective systems look like. We know how to find weak points and fix them. What's missing is the will to do it and leadership to facilitate and/or finance. If you are in a position of knowledge, influence, or leadership in this industry, then it's on you—because the next failure won't be due to a lack of guidance; it will be due to a failure to act.

So, act. Start now. And do it like lives depend on it—because they do.

References

- Global Food Safety Initiative (GFSI). "GFSI Overview." https://mygfsi.com/who-we-are/overview/.

- Medintz, S. "You Can't Take Daily Harvest to Court if Its Food Made You Sick." Consumer Reports. July 22, 2022. https://www.consumerreports.org/money/mandatory-binding-arbitration/meal-delivery-services-and-mandatory-binding-arbitration-a1799836056/.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). "Investigations of Foodborne Illness Outbreaks." Content current as of April 4, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/food/outbreaks-foodborne-illness/investigations-foodborne-illness-outbreaks.

- FDA. "Outbreak Investigation of Listeria monocytogenes: Dole Packaged Salad (December 2021)." https://www.fda.gov/food/outbreaks-foodborne-illness/outbreak-investigation-listeria-monocytogenes-dole-packaged-salad-december-2021.

- FDA. "FDA Investigation of Cronobacter Infections: Powdered Infant Formula (February 2022)." Content current as of August 1, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/food/outbreaks-foodborne-illness/fda-investigation-cronobacter-infections-powdered-infant-formula-february-2022.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). "2015 Outbreak of Listeria Infections Linked to Blue Bell Creameries." June 10, 2015. https://archive.cdc.gov/www_cdc_gov/listeria/outbreaks/ice-cream-03-15/index.html.

- FDA. "Investigation of Adverse Event Reports: French Lentil & Leek Crumbles (June 2022)." Content current as of October 25, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/food/outbreaks-foodborne-illness/investigation-adverse-event-reports-french-lentil-leek-crumbles-june-2022.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). "BrucePac Recalls Ready-to-Eat Meat and Poultry Products Due to Possible Listeria Contamination." October 9, 2024. https://www.fsis.usda.gov/recalls-alerts/brucepac-recalls-ready-eat-meat-and-poultry-products-due-possible-listeria.

- FDA. "Outbreak Investigation of E. coli O157:H7: Onions (October 2024)." Content current as of December 3, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/food/outbreaks-foodborne-illness/outbreak-investigation-e-coli-o157h7-onions-october-2024.

- USDA. "Boar's Head Provisions Co. Recalls Ready-To-Eat Liverwurst And Other Deli Meat Products Due to Possible Listeria Contamination." July 26, 2024. https://www.fsis.usda.gov/recalls-alerts/boars-head-provisions-co--recalls-ready-eat-liverwurst-and-other-deli-meat-products.

- USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service. "Noncompliance Report, Establishment Number(s) M12612+P12612 from 08/01/2023 to 08/02/2024." August 1, 2023. https://www.fsis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media_file/documents/Non-Compliance_Reports-812023-To-822024.pdf.

- FDA. "Outbreak Investigation of Listeria monocytogenes: Frozen Supplemental Shakes (February 2025)." Content current as of February 24, 2025. https://www.fda.gov/food/outbreaks-foodborne-illness/outbreak-investigation-listeria-monocytogenes-frozen-supplemental-shakes-february-2025

- Woudenberg, M. and C.J. Unis. "Systems Thinking: Skills and Insights to Resolve Wicked Problems." January 29, 2023. https://www.polymathicbeing.com/p/systems-thinking.

- Marler Blog. "Confidential Disclosure re Abbott Laboratories' Production Site in Sturgis, Michigan." October 19, 2021. https://www.marlerblog.com/files/2022/04/Redacted-Confidential-Disclosure-re-Abbott-Laboratories-10-19-2021_Redacted-1-1.pdf.

Cori Muse is a Food Safety and Regulatory Consultant and the Owner of Muse Food Safety Solutions LLC. She is also an independent GFSI Auditor, an alumni of PepsiCo/Frito-Lay, and has an extensive background working in the food industry over 14 years.