30th Anniversary Retrospective

A Look at Poultry Safety and Salmonella Testing—Then vs. Now

SCROLL

DOWN

In the U.S., we have seen many changes taking place on the regulatory front over the past half-year. Some of these changes were anticipated or considered likely, and some have been unprecedented—such as the upending of the Food and Drug Administration's (FDA's) newly restructured Human Foods Program and workforce.

Food safety professionals and advocates both within and outside the federal workforce have expressed a range of sentiments in response to these changes by the Trump administration. Among the most prominent of these reactions is a feeling of "whiplash"—federal programs and staffers' jobs have been cut and then sometimes reinstated within days or weeks. Steep tariffs have been slapped on America's trading partners and then suddenly revoked. And a host of long-awaited regulations and proposals meant to improve food safety have been significantly postponed or slashed. These include FSMA 204 (FDA's Food Traceability Final Rule), which has been delayed by 30 months as of this writing,1 and the U.S. Department of Agriculture's (USDA's) proposed regulatory framework for Salmonella in raw poultry. The need to improve the detection and mitigation of Salmonella in poultry is not new, but it is changing—as I discuss in this issue's 30th Anniversary Retrospective.

Withdrawal of FSIS' Proposed Salmonella Framework

In late April, the USDA's Food Safety and Inspection Service (USDA-FSIS) announced the withdrawal2 of its proposed framework to reduce Salmonella contamination of raw poultry. The framework was published in August 2024, after years of development and adjustment. The National Advisory Committee on Microbiological Criteria for Foods (NACMCF), which was disbanded by the Trump administration in early March,3 helped guide the revision of the framework and provided recommendations for interventions and testing.

The goal of the proposed framework was to reduce the cases of human salmonellosis attributable to the consumption of poultry because, despite the effectiveness of FSIS' current Salmonella verification sampling program in reducing the proportion of poultry products contaminated with the pathogen, it has not translated into a reduction in foodborne illness. Former USDA-FSIS Under Secretary for Food Safety Dr. José Emilio Esteban and former USDA-FSIS Deputy Under Secretary for Food Safety Sandra Eskin discussed this challenge in an October 2024 bonus episode of the Food Safety Matters podcast.4

Upon the withdrawal of the proposed framework in April, FSIS stated that it had "…determined that additional consideration is needed in light of the feedback received during the public comment period, which closed on January 17, 2025." While the National Chicken Council, an industry trade group, applauded the move, many longtime food safety professionals and advocates did not.

Ms. Eskin, who served at USDA-FSIS during the development of the framework and who currently serves as the CEO of STOP Foodborne Illness, stated in response to the withdrawal, "The decision to withdraw the Salmonella poultry framework sends the clear message that [Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.'s] 'Make America Healthy [Again]' initiative does not care about the thousands of people who get sick from preventable foodborne Salmonella infections linked to poultry. The proposal was developed with robust stakeholder input, and the decision to withdraw it was made before FSIS even had an opportunity to review the extensive docket."3

Among the tenets of the proposed framework,5 FSIS would have conducted a routine sampling, testing, and verification testing program for Salmonella in raw chicken carcasses and parts. Details on the planned testing protocols had not been finalized as of the time of the withdrawal, although FSIS had been "…actively working to explore technologies that may have the capability of WGS [whole genomes sequencing] in determining serotype and reduce the current [testing] timeframe."5 This timeframe, as stated in the framework, could have spanned as little as 5 days using non-routine molecular serotyping methodology, to as long as 14 days using WGS. "All timeframes and methods are likely to change as FSIS continuously incorporates new laboratory technologies into its sampling verification program," FSIS stated in the framework.5

Testing for Salmonella: Past Developments and Present Initiatives

Food safety scientists have been working to improve and refine testing for Salmonella in poultry for decades. Nearly 30 years ago, when Food Safety Magazine was still Food Testing & Analysis (Figure 1), authors from the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) penned an article in the February/March 1996 issue on the food industry's quest for better detection of Salmonella in chicken.6

FIGURE 1. The cover of Food Testing & Analysis' February/March 1996 issue

The authors explained, "In recent years, the need for accurate, economical monitoring by the food industry has stimulated the development, validation, and marketing of diagnostic kits useful for rapid detection of Salmonella in food samples… To protect public health and reduce Salmonella-related disease outbreaks, a rapid, reliable, and sensitive method is needed for specific detection of this microbial pathogen in contaminated chicken meat."6 The method explored in the article is an "improved sample-based processing protocol that enables PCR [polymerase chain reaction]-based detection of Salmonella Typhimirium in artificially contamination chicken meat."

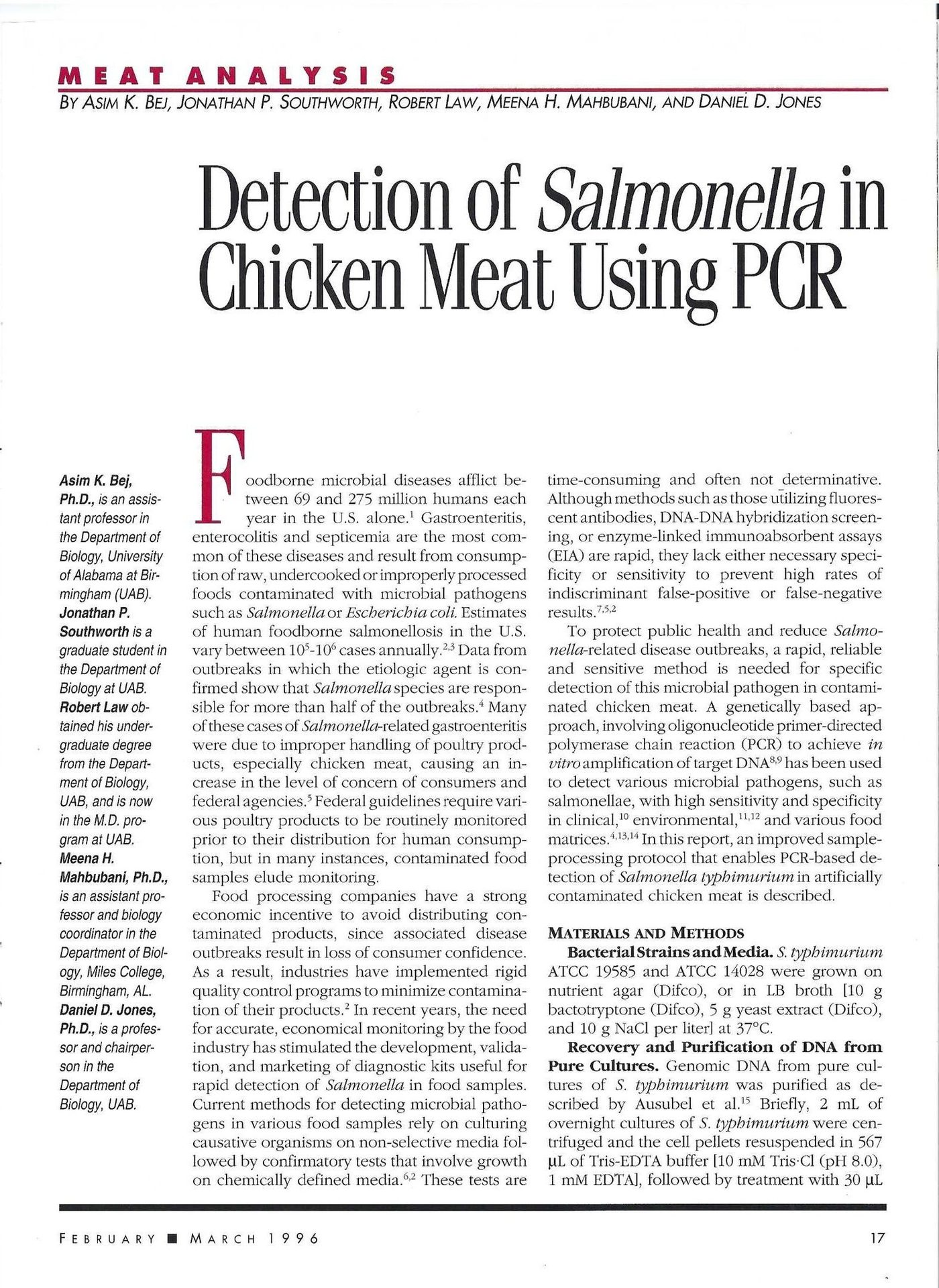

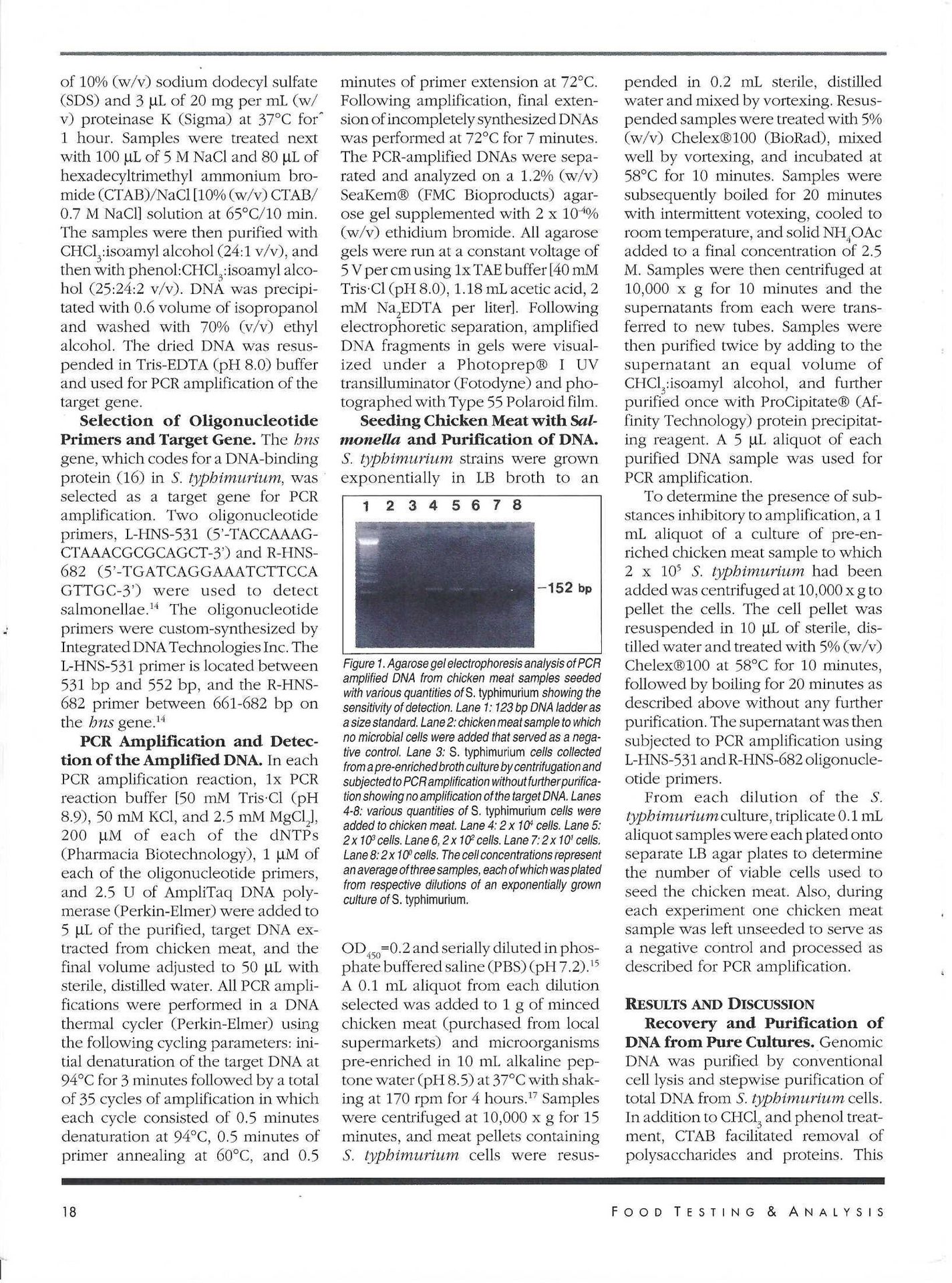

A molecular serotyping method first introduced in 1983, PCR has enabled rapid advances in food safety since the 1990s, particularly with the development and application of real-time PCR (qPCR). The UAB authors acknowledged the possibilities offered by advanced PCR technology, noting, "A genetically based approach, involving oligonucleotide primer-directed [PCR] to achieve in vitro amplification of target DNA has been used to detect various microbial pathogens, such as Salmonellae, with high sensitivity and specificity in clinical, environmental, and various food matrices" (Figures 2 and 3).

FIGURES 2-3. "Detection of Salmonella in Chicken Meat Using PCR," published in Food Testing & Analysis (February/March 1996), by Asim K. Bej, Ph.D., Jonathan P. Southworth, Robert Law, Meena H. Mahbubani, Ph.D., and Daniel D. Jones, Ph.D.

Ensuring Poultry Safety: Where Do We Go From Here?

The novelty of PCR testing in food safety has since given way to whole genome sequencing and other cutting-edge technologies. However, taking a look back at the new work that was being undertaken in 1996 for better detection of Salmonella in poultry, in an effort to protect public health, is enlightening. It demonstrates how far science and industry have come in terms of sampling, testing, and verification technology. It also casts the Trump administration's revocation of FSIS' Salmonella framework in a strange light.

"Food processing companies have a strong economic incentive to avoid distributing contaminated products, since associated disease outbreaks result in loss of consumer confidence," the UAB authors wrote in 1996. The architects of the modern-day FSIS framework, along with their scientific advisors, would certainly agree with this decades-old statement and underline its significance to the withdrawn regulation.

The poultry industry, on the other hand, believes it's already meeting its food safety and consumer obligations. It also says that the Salmonella performance standards—which were introduced in 1996 and will remain in force in lieu of the passage of the framework—are adequate to ensure the safety of poultry products.7 The public feedback received on the proposed framework won't go totally to waste, however—FSIS plans to evaluate the current performance standards based on the feedback received prior to January 17. This means the agency acknowledges that some adjustments to the standards may be necessary, from a food safety standpoint.

Nonetheless, in an earlier rebuttal to the framework, the National Chicken Council stated, "When the data from both [CDC's] FoodNet Fast and IFSAC [the Interagency Food Safety Analytics Collaboration] are analyzed based on per-pound consumption of chicken, the rate of salmonellosis in the U.S. has decreased from about 77 illnesses for every 1 million pounds of chicken consumed in 1996, to about 49 illnesses per 1 million pounds of chicken consumed in 2022. This marks a 36 percent decrease in illness on a per-pound basis, which is clear evidence that performance standards alone can and [do] drive food safety changes when viewed in the proper context."8

The data comparison between 1996 and today is interesting—as is the comparison of where the poultry industry stood in terms of Salmonella detection technologies available then versus now. While USDA, under the Trump administration, appears to have reversed its stance on stricter regulation of Salmonella in poultry, the private sector will continue to refine and advance the science of pathogen detection. These private-sector developments will contribute to the ongoing effort, outlined by FSIS in its revoked framework, "to develop rapid, reliable, Salmonella quantification and serotyping technologies"5 in order to reduce pathogenic contamination of raw poultry and better support public health.

“Big data and AI technologies, such as machine learning, show promise for informing AMR surveillance and mitigation efforts.”

Regards,

Adrienne Blume, M.A.

Editorial Director

References

- Henderson, B. "FDA Delays FSMA 204 Traceability Rule Compliance Date by 30 Months." Food Safety Magazine. March 20, 2025. https://www.food-safety.com/articles/10245-fda-delays-fsma-204-traceability-rule-compliance-date-by-30-months.

- Henderson, B. "USDA Withdraws Proposed Regulatory Framework for Salmonella in Poultry After Years of Development." Food Safety Magazine. April 24, 2025. https://www.food-safety.com/articles/10343-usda-withdraws-proposed-regulatory-framework-for-salmonella-in-poultry-after-years-of-development.

- Henderson, B. "Key Federal Food Safety Advisory Committees, NACMCF and NACMPI, Have Been Terminated." Food Safety Magazine. March 7, 2025. https://www.food-safety.com/articles/10196-key-federal-food-safety-advisory-committees-nacmcf-and-nacmpi-have-been-terminated.

- Food Safety Magazine Editorial Team. "Esteban and Eskin: On the Frontlines of the Food Safety Fight Against Salmonella in Poultry." Food Safety Matters podcast. October 1, 2024. https://www.food-safety.com/articles/9773-esteban-and-eskin-on-the-frontlines-of-the-food-safety-fight-against-salmonella-in-poultry.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service (USDA-FSIS). "Salmonella Framework for Raw Poultry Products: A Proposed Rule by the Food Safety and Inspection Service on 08/07/2024." Docket No. FSIS-2023-0028. Withdrawn April 25, 2025. Federal Register. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/08/07/2024-16963/salmonella-framework-for-raw-poultry-products.

- Bej, A.K., J.P. Southworth, R. Law, M.H. Mahbubani, and D.D. Jones. "Detection of Salmonella in Chicken Meat Using PCR." Food Testing & Analysis. February/March 1996.

- USDA-FSIS. "Performance Standards Salmonella Verification Program for Raw Poultry Products." Updated March 2, 2021. https://www.fsis.usda.gov/policy/fsis-directives/10250.2.

- National Chicken Council. "Re: Docket No. FSIS-2023-0028: Salmonella Framework for Raw Poultry Products." January 17, 2025. https://www.nationalchickencouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/NCC-Comments-to-Docket-No.-FSIS-2023-0028.pdf.