REGIONAL CULTURE

By Lone Jespersen, Ph.D., Principal, Cultivate; John David, Global Scientific Marketing Manager, 3M; and Sophie Tongyu Wu, Ph.D., Senior Research Assistant at University of Central Lancashire

Global Food Safety Culture: Latin America

Latin American leans toward indirect, high-context communication and relationship-based culture

Image credit: Sunan Wongsa-nga/iStock / Getty Images Plus via Getty Images

SCROLL DOWN

Panelists Michele Fontanot, Ph.D. (Professional Service Manager, 3M Latin America), Paola Lopez (Quality Assurance Manager, Sigma), and Lone Jespersen, Ph.D. (Cultivate, Switzerland) identified three key characteristics on the food safety culture in Latin America region: a culture of caring, empowerment, and authentic food safety culture as a competitive advantage.

Culture of Caring

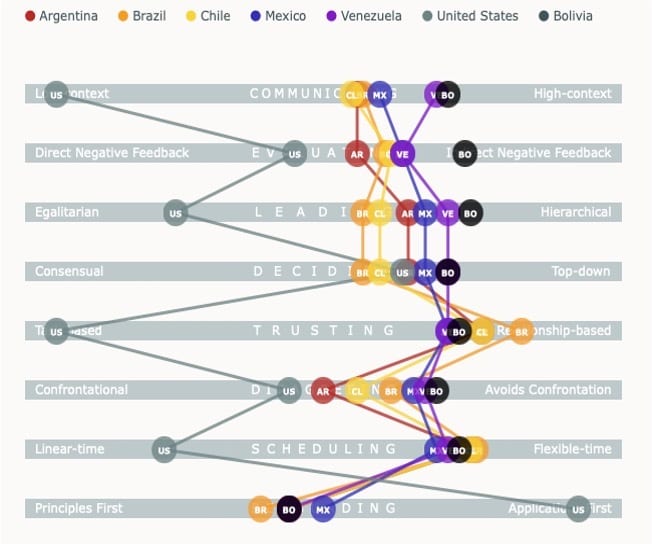

A deep sense of "culture of caring" prevails in Latin America. This relationship-based culture, with its relatively indirect, high-context communication (Figure 1), signals the importance of trust-building at work. As one panelist described, building relationships and coordinating teamwork are like dancing. Cultivating food safety culture is to foster a sense of team, create innovative teamwork, nurture meaning and relevance about food safety in everyone, and consequently transform food safety culture to a natural way of life. Since people's learning styles differ, it is important to respect the differences and work on the similarities. As the webinar panelists noted, "A quality system must have elements that encourage a sense of belonging."

While a trusting food safety culture can be a competitive advantage, this relationship-centric culture could, on the other hand, encumber opportunities for challenging food safety as a team. Therefore, ways to critically discuss food safety can be integrated into work relationships.

The Latin American countries are also relatively flexible in time management. They lean toward "principle first," indicating the preference of learning about concepts and principles before adoption, unlike the U.S., one of their biggest trading partners (Figure 1).1

Indeed, it is important to understand the culture of one's customers in a globalized world. Given that regional cultural characteristics play a role in developing food safety culture, keeping the cultural differences in mind can help foster trust and relationships in working with global customers.

Importance of Empowerment

Empowerment and encouragement are fundamental in cultivating food safety culture in the Latin American region. The organizational culture is meant to support everyone in the ownership of their role—via teaching them the knowledge, developing their skills, giving them time to mature, and importantly, connecting the responsibilities as a network. As a result, people understand how they fit together in the food safety system and in the workflow; this sense of personal relevance, in turn, evokes pride in what they are doing.

Dr. Michele Fontanot recounted an anecdote at her previous employer, where, to help the frontline own the process, she engaged the operations teams and supervisors in building their Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) plan. Traditionally, however, the food safety and quality (FSQ) team held exclusive ownership to the HACCP plan. Although it took three years to revamp the system, the revised flow worked well, and the frontline was able to take responsibility of their line and the products. Indeed, food safety is not framed around punitive measure; its value is rooted in encouraging people to find ways to improve and giving power to make them stronger.

Authentic Culture as a Competitive Advantage

While food safety is not a competitive advantage, food safety culture is. A 2014 study2 found that 54 percent fewer mistakes were made in the business of a mature culture, leading to lower cost of quality, including prevention cost (e.g., process equipment preventative maintenance and employee training), appraisal cost (e.g., food safety and quality audits), internal failure cost (e.g., waste and rework of products), and external failure cost (e.g., product withdrawal and recall).

Two motivators are found in food safety culture in the Latin American region: authenticity and competitive advantage. Giving authenticity to food safety culture starts from the leaders, who set this vision in business expectations (Figure 2). As most FSQ decisions are made by the FSQ teams, it is necessary to plant food safety in the strategic initiative in the business leadership. Behaviors and systems should align with the organizational culture and company's food safety message, and leaders should promote food safety meanings on a daily basis (Figure 3). A FIRST model (Fundamentals, Infrastructure, Risk analysis, Scorecard, and Training) helps identify and evaluate quality culture, as well as capture mindset, skills, and infrastructure.

FIGURE 2. Principles of Authentic Quality Culture

FIGURE 3. Align Behaviors with Quality Culture

Being a crucial player in the global food chain inspires Latin American countries to pursue positive food safety culture as a competitive advantage to help fulfil their duty. As the industry grows with the market, there is a rising need to standardize food safety culture language among Latin American countries—i.e., what food safety culture means, and what is expected from each person. The lack of a common language renders double standards facing local and global markets. Recalling "authentic quality culture" (Figure 2), there is a need to create an integrated management system, to maximize productivity along with food safety and quality. It is not only about training and audits, but also "teamwork like a choreographed dance." This emphasizes shared responsibility across and throughout the organization so that everyone has a role in food safety, owns the process, and aligns with the company's expectations—or tengo, sé, puedo ("I have, I know, I can").

References

- Meyer, Erin. The Culture Map: Breaking Through the Invisible Boundaries of Global Business. New York, New York: Public Affairs (2014).

- Srinivasan, Ashwin and Bryan Kurey. "Creating a Culture of Quality." Harvard Business Review. April 2014. https://hbr.org/2014/04/creating-a-culture-of-quality.

Lone Jespersen, Ph.D., is a principal at Cultivate, an organization dedicated to helping food manufacturers globally make safe, great-tasting food through cultural effectiveness. She has significant experience with food manufacturing, having previously spent 11 years with Maple Leaf Foods. Dr. Jespersen is also a member of the Food Safety Magazine Editorial Advisory Board.

John David is Global Scientific Marketing Manager at 3M. He holds a master's degree in molecular biology and genetics and a bachelor's degree in biological sciences, both from the University of Delaware.

Sophie Tongyu Wu, Ph.D., is a Senior Research Assistant at University of Central Lancashire and a member of Cultivate SA. She leads a food safety culture improvement project at ten UK food manufacturing companies to collect organization-wide feedback for targeted action. Dr. Wu holds a Ph.D. in food science and technology from Purdue University and a bachelor's degree in biology from the University of Wisconsin–Madison.