SPOTLIGHT

Nitrite for Meat Preservation: Controversial, Multifunctional, and Effective

Nitrite has several functional purposes in meat, including the formation and conservation of a stable red color and the inhibition of growth of C. botulinum

By Anette Granly Koch, Ph.D., Scientific Manager, Danish Meat Research Institute (DMRI), Danish Technological Institute (DTI); Gudrun Margret Jónsdóttir, M.Sc., Consultant, DMRI, DTI; Marlene Schou Grønbeck, M.Sc., Scientific Manager, DMRI, DTI; and Gry Carl Terrell, M.Sc., Business Manager, DMRI, DTI

SCROLL DOWN

Video credit: Jure Kotnik/Creatas Video+/Getty Images Plus via Getty Images

> SPOtliGHT

The practice of preserving meat with salt dates back to ancient times, with its origins rooted in the saline deserts of Hither Asia and in coastal regions. The precise early history has been lost. In ancient Palestine around 1600 B.C., salt preservation was common, largely due to the abundant supply from the Dead Sea. By 1200 B.C., the technology for producing sea salt was already known in China, demonstrating the wide geographical spread of this essential food preservation method.

Preservation of meat and fish by salting was well-developed already in antiquity, and the present methods of dry salting, wet salting, and combinations of the two became established through medieval times. During the late 1800s and early 1900s, the curing of meat was widely industrialized, and while conventional wet salting in a vat (immersion or pickle salting) continued to be in use, new variants of wet salting were introduced, such as the use of perforated pumping needles to inject brine into the meat (stitch salting).

The first official guidelines for the use of nitrite in meat curing were drafted by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) in 1925, reflecting growing scientific understanding and regulatory oversight of food safety.

The use of nitrite has several functional purposes, of which the formation and conservation of a stable red color in meat and the inhibition of the growth of Clostridium botulinum are particularly important. In addition, nitrite exerts a desirable antioxidant activity and contributes to the formation of cured meat flavors. However, the understanding of the technological effect of nitrite only slowly developed, and for a long period up to the first half of the 1900s, nitrate was considered to be the active agent. However, today it is known that nitrite, rather than nitrate, is the active agent.

Nitrite Chemistry

In modern meat curing processes, curing agents are commonly added as sodium nitrate (NaNO3), potassium nitrite (KNO2), or sodium nitrite (NaNO2).

Nitrate (NO3−) itself is not directly reactive in meat; it requires conversion to nitrite (NO2−) by bacteria with nitrate reductase activity, typically supplied by starter cultures. This microbial reduction accelerates the formation of nitrite, which is the truly reactive curing agent.

Once added, nitrite dissociates in the mildly acidic environment of the muscle (pH 5.5 to 6.5), forming nitrous acid (HNO2).1,2 These nitrous acids can further react to form dinitrogen trioxide (N2O3), a reactive intermediate, which decomposes to produce nitric oxide (NO) and regenerate nitrite. Nitric oxide is the key molecule responsible for both the development of cured meat color and flavor.1,3

Color Development

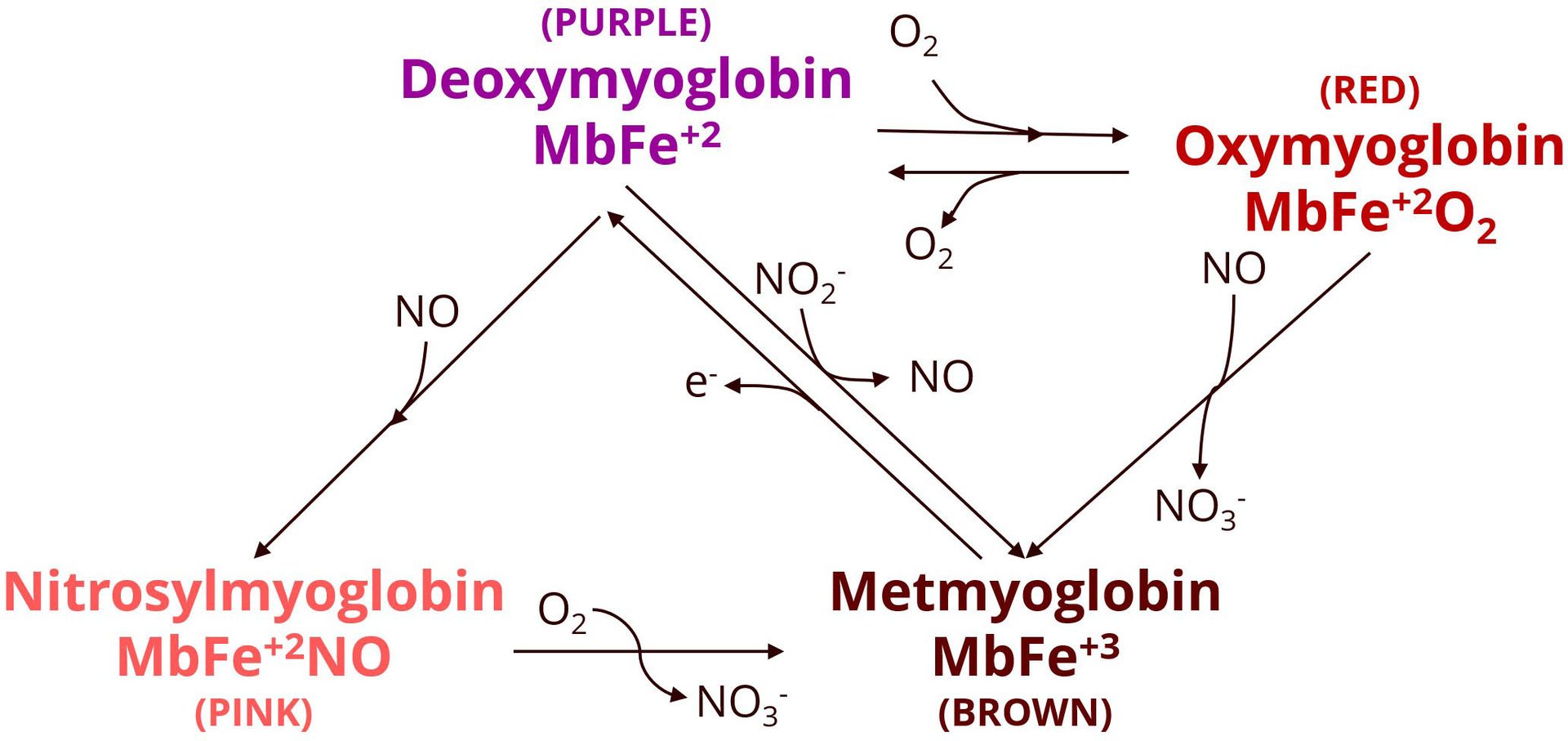

Fresh meat color is determined by the oxidation state of the iron in the center of myoglobin, the oxygen-binding protein in muscle. When the iron is in a ferrous state (Fe2+), myoglobin exists as deoxymyoglobin (MbFe2+), giving meat a purple-red color (see Figure 1). In the presence of oxygen, deoxymyoglobin is converted to oxymyoglobin, which imparts a bright red color commonly associated by consumers with freshness. Both forms will eventually be converted to metmyoglobin (MbFe3+), which is brown and considered undesirable by consumers.

FIGURE 1. Pathways of myoglobin transformation and color development in meat (Credit: Danish Meat Research Institute)

Note: Deoxymyoglobin, oxymyoglobin, metmyoglobin, and nitrosylmyoglobin interconvert depending on the presence of oxygen, nitrite, and nitric oxide. The formation of nitrosylmyoglobin, responsible for the pink color of cured meats, occurs through the reaction of deoxymyoglobin with nitric oxide generated from nitride during curing. Oxidation and reduction reactions, as well as binding of NO or O2, determine the color outcome and stability in meat products.

During curing, nitrite oxidizes myoglobin to metmyoglobin, and in the process nitrite itself is reduced to nitric oxide.3 The metmyoglobin can then be reduced back to deoxymyoglobin by reducing agents. Nitric oxide then binds to deoxymyoglobin to form nitrosylmyoglobin (MbFe2+NO), which is responsible for the stable pink color of cured meats.3 This compound can be further stabilized by heat treatment, which denatures the globin portion of the molecule, resulting in nitrosyl heme-chromogen—the pigment that gives cooked cured meats like ham their stable pink color. To achieve this preferred color, it is generally sufficient to use 25–50 milligrams of nitrite per kilogram (mg/kg) of product,1 although higher concentrations can result in even more stable coloration.

Flavor and Antioxidative Effects

In addition to color formation, nitrites and nitrates contribute significantly to the flavor and oxidative stability of cured meats. Off-flavors in meat products are often related to lipid oxidation, e.g., warmed-over flavor, which is described as a stale, rancid, or cardboard-like flavor and commonly associated with reheated meat. Nitrite and its derivatives, particularly nitric oxide, have potent antioxidative properties. Nitric oxide is highly reactive and can act both as an oxidizing agent (NO+) and a reducing agent (NO−), allowing it to participate in a variety of redox reactions within the meat matrix.

Nitrite at levels as low as 50–75 mg/kg is sufficient to provide the distinctive cured meat flavor and to inhibit the development of warmed-over flavor.4,5 Nitric oxide helps prevent the initiation of lipid oxidation by rapidly neutralizing reactive oxygen species and interrupting the radical chain reactions that drive lipid degradation.2,3 The free iron in myoglobin, which can catalyze both lipid and protein oxidation, is sequestered when nitrite is present, thus preventing these pro-oxidative reactions.5

Additionally, nitrosylmyoglobin itself acts as a lipid antioxidant, both through the dissociation of nitric oxide and by directly reacting with activated oxygen species that would otherwise propagate lipid oxidation.2,3

Nitrite is also involved in the formation of several volatile compounds that contribute to the characteristic flavor of cured meats. These compounds primarily result from reactions with lipids and proteins, but also by reactions between nitric oxide and sulfur-containing amino acids, such as cysteine.5 While sodium chloride (table salt) is a potent flavor enhancer and has its own effects on the sensory profile of cured meats, nitrite is essential for the development and long-term retention of the unique cured meat flavor, especially by suppressing rancidity even at relatively low concentrations.1

“New EU regulations, effective from October 9, 2025, are mandating a reduction of the maximum permissible levels of nitrites that may be added to processed meat.”

Antimicrobial Benefits of Nitrite

Several factors influence the antimicrobial effect of nitrite, such as hygienic status, pH, water activity, iron in meat, and the concentration of other salts. Furthermore, nitrite is degraded during storage of the product, usually by oxidation and/or further reduction to NO. All evidence points to the in-going amount of nitrite, rather than the residual amount of nitrite in the product, as exerting an inhibitory effect on C. botulinum,6 whereas the inhibitory effect on Listeria monocytogenes depends on residual nitrite.

Regulation is Changing

The addition of nitrite to meat has been regulated for a long time by authorities throughout the world. New EU regulations, effective from October 9, 2025, are mandating a reduction of the maximum permissible levels of nitrites that may be added to processed meat. For heated and non-heated meat products, the permissible level is reduced from 150 ppm Na-nitrite to 120 ppm. In canned, shelf-stable meat products heated to F0 > 3, the permissible level is reduced from 100 ppm to 82 ppm Na-nitrite. Furthermore, a limit for residual nitrite (i.e., the amount of nitrite remaining in the final product) will be introduced, ranging from 25–50 ppm for various categories, with exceptions for certain traditionally cured products.7

Nitrite and Clostridium

C. botulinum is one of the main pathogens being controlled by using salt and nitrite. C. botulinum is important to control in refrigerated products, as well as in shelf-stable cured meat products packed in hermetically sealed containers (i.e., cans or vacuum packages), especially due to the risk of generating the potent and dangerous neurotoxin formed during the growth of C. botulinum. Also, some species of Clostridium are spoilers, producing gas (blown packages) and foul odors. The increased legislative pressure to reduce the use of nitrite must be balanced with the shelf life and food safety advantages, but for canned meat products, a closer look at the D120°C values for the most heat-resistant variables has revealed a possible gap in data to document that the level of shelf life and food safety is maintained when the addition of nitrite is reduced.

The sodium levels in cold-stored meat products have been reduced over recent years due to vascular health concerns. The result is that the sodium levels in many products now are below the proven 3–3.5 percent salt (WPS) necessary to control C. botulinum growth. Therefore, it is especially important to use preservatives other than salt. A common additional preserving agent is lactate. By using the C. botulinum model found in the model collection DMRI Predict,8 it is possible to find combinations of salt, nitrite, and lactate that will prevent spore germination and growth of C. botulinum for up to 56 days of refrigerated storage of modified atmosphere packaged (MAP) meat products.

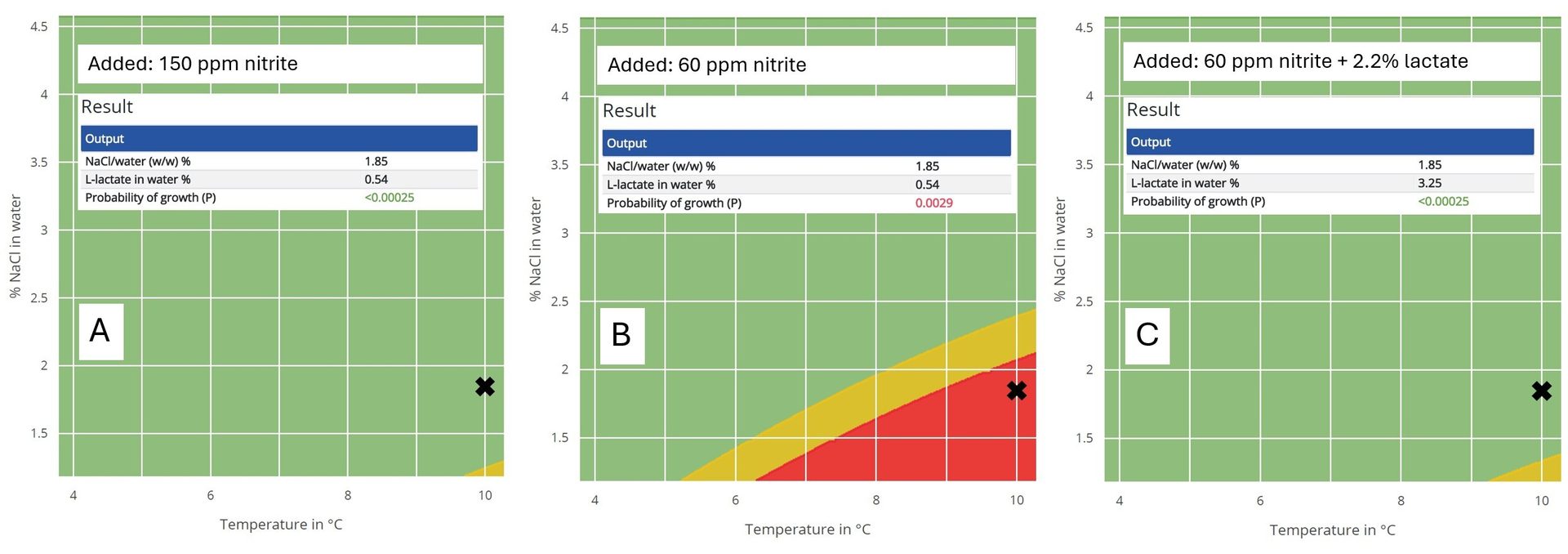

If, for example, a heated sausage is stored at 10 °C (50 °F) and only added 1.2 percent salt (1.8 v/v percent), there is a high risk of growth of C. botulinum. However, if 150 ppm of nitrite is added, then the product is safe. The amount of nitrite can be reduced to 60 ppm, for example, but to obtain a safe product there is a need for additional preservation. DMRI Predict shows that the addition of 2.2 percent Na-lactate will boost the level of safety of the product with the combination preservation to be on par with preservation using 150 ppm of nitrite alone (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. Predicted risk for the growth of C. botulinum in modified atmosphere packaged meat (pH 6) stored at 10 °C (50 °F), added 1.8 volume percent salt/water; legend: 150 ppm Na-nitrite (A), 60 ppm Na-nitrite (B), or 60 ppm Na-nitrite + 2.2 percent Na-lactate (C) (Credit: DMRI Predict)

For canned meat, the guidelines from Codex Alimentarius have been followed for decades. The recommendations to produce safe canned meat are based on three standard conditions combined with heat treatments with F0-values varying from 0.5–1.5.9 The standard conditions are:

- Low spore counts in the meat and other ingredients used

- Addition of 150 ppm of nitrite

- Achieving 3–5.5 percent salt in the WPS.

Facing the upcoming EU-mandated reduction of added nitrite, the Danish Meat Research Institute (DMRI) has found a lack of documentation to support that an F0 cook < 3 with only 120 ppm of nitrite added is just as safe and shelf-stable as if 150 ppm of nitrite was added. DMRI has also found a lack of documentation to support that an F0 cook ≥ 3 is equally safe and shelf-stable with the addition of 82 ppm of nitrite instead of 150 ppm.

The heat resistance of Clostridium spores (spoilers, botulinum, and perfringens) varies, with D120°C values in the range of approximately 0.5–2.7 minutes. C. perfringens and the putrefactive anaerobes are on one end of the scale as the most heat resistant, and C. botulinum is on the other end of the scale as the most heat sensitive. This means that although a heat treatment equivalent to 3 minutes at 121 °C (250 °F) is sufficient to safeguard against C. botulinum, it does not result in significant inactivation of spores of the spoilage-causing strains of Clostridium, and there may be a risk of growth during storage if the products are not adequately preserved.

Good shelf life for canned foods depends on the correct combination of applied heat treatment, salt, and nitrite. A newly initiated project at DMRI is investigating the role of nitrite concentrations in the range of 82–150 ppm to demonstrate differences (if any) and establish how the addition of more salt and/or other additives can compensate for the reduction of nitrite in canned meat.

Nitrite and Listeria monocytogenes

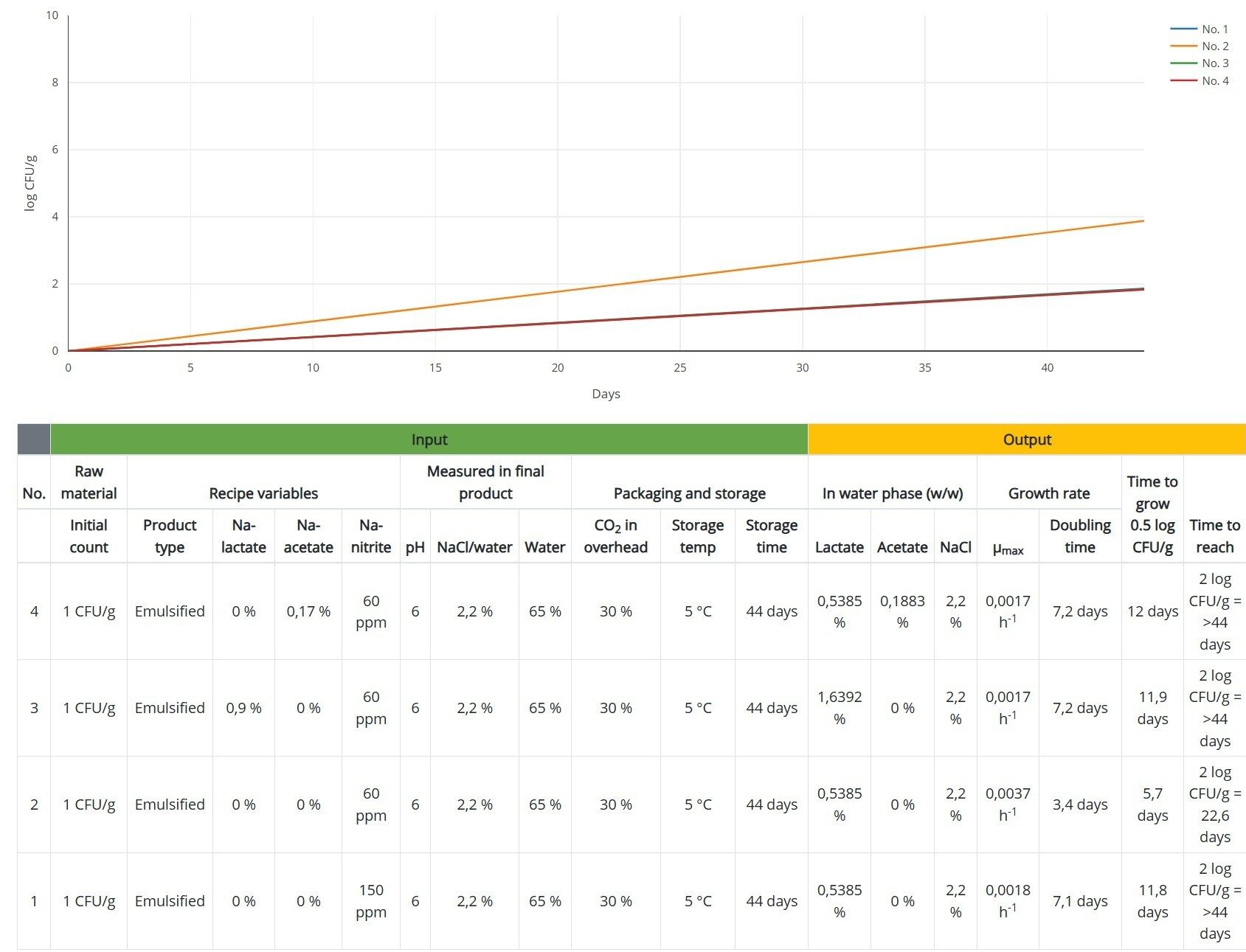

Clostridium is not the only pathogen that can be controlled using nitrite. Another example is inhibiting the growth of L. monocytogenes. Using the Listeria model on DMRI Predict shows that reducing the level of added nitrite from150 ppm to 60 ppm cuts the shelf life by 50 percent, but the addition of either 0.9 percent Na-lactate or 0.17 percent Na-acetate could compensate for the reduction in nitrite (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3. Predicted growth of L. monocytogenes in heat-treated meat product with added 150 ppm Na-nitrite (No. 1) vs. 60 ppm Na-nitrite alone (No. 2) or in combination with 0.9 percent Na-lactate (No. 3) or 0.17 percent Na-acetate (No. 4) (Credit: DMRI Predict)

Nitrite and Bacillus cereus

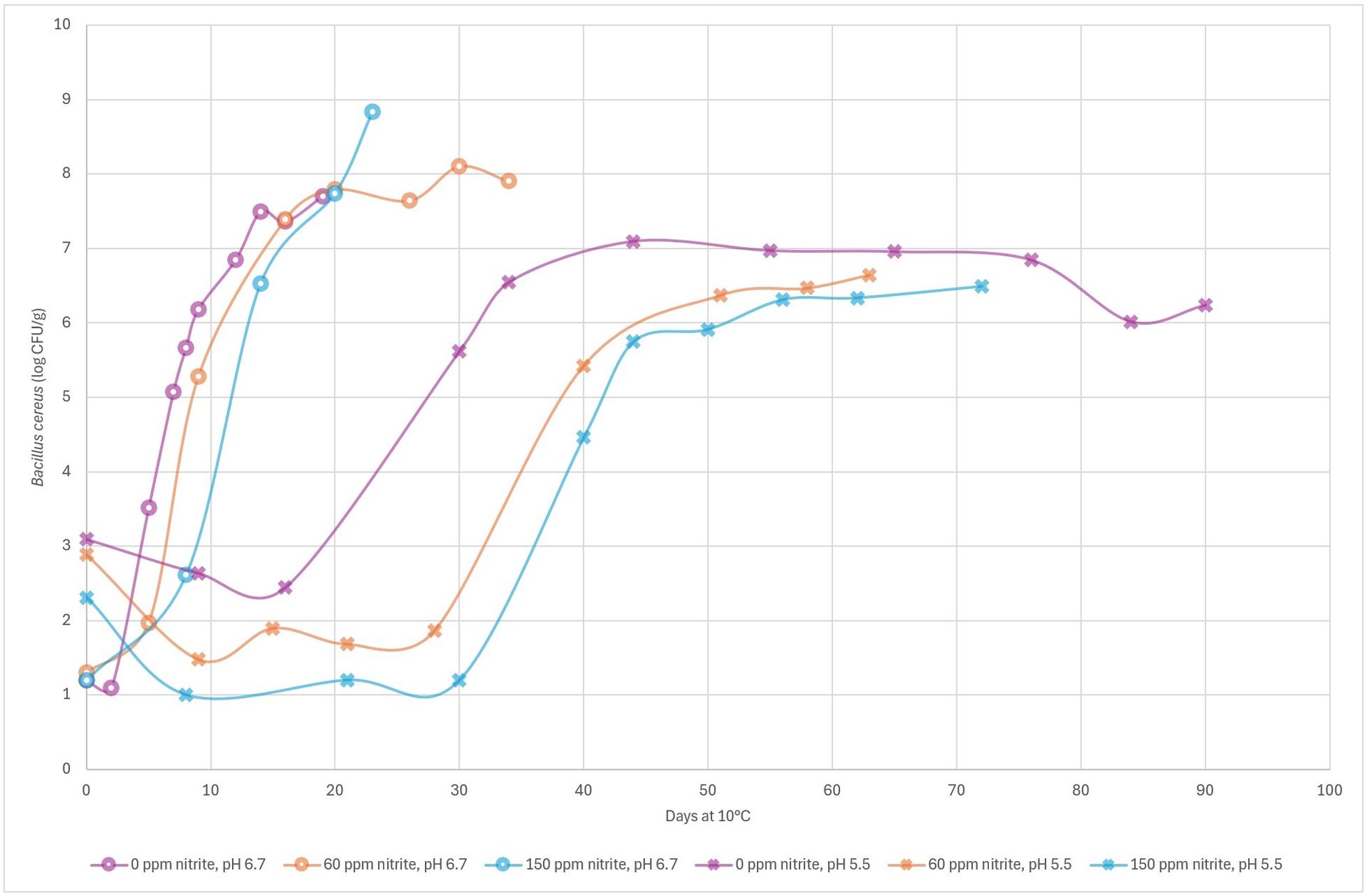

Another pathogen that is receiving increased attention is B. cereus. The growth of this pathogen is also affected by nitrite. Challenge tests in processed meat, low in salt (down to 0.9 percent salt/water), stored at 10 °C (50 °F), and packaged in vacuum or modified atmosphere (30 percent CO2/70 percent N2), have shown that, the more nitrite added, the less growth is detected. Nitrite is much more effective at pH 5.5 compared to pH 6.7, where the effect of 60 ppm vs. 150 ppm appears to be comparable.

In modified atmosphere packaged meat, the time for 3 log growth at pH 6.7 is approximately 6, 8, and 11 days at 0 ppm, 60 ppm, and 150 ppm of added nitrite, respectively. At pH 5.5, the time for 3 log growth is approximately 32, 43, and 43 days at 0 ppm, 60 ppm, and 150 ppm of added nitrite, respectively (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4. Growth of B. cereus in processed meat with 0.9 percent salt/water, packaged in modified atmosphere (30 percent CO2/70 percent N2) and stored at 10 °C (50 °F), comparing products at pH 5.5 (X) vs. pH 6.7 (O) with 0 ppm of nitrite (purple), 60 ppm of nitrite (orange), or 150 ppm of nitrite (blue) added (Credit: Danish Meat Research Institute)

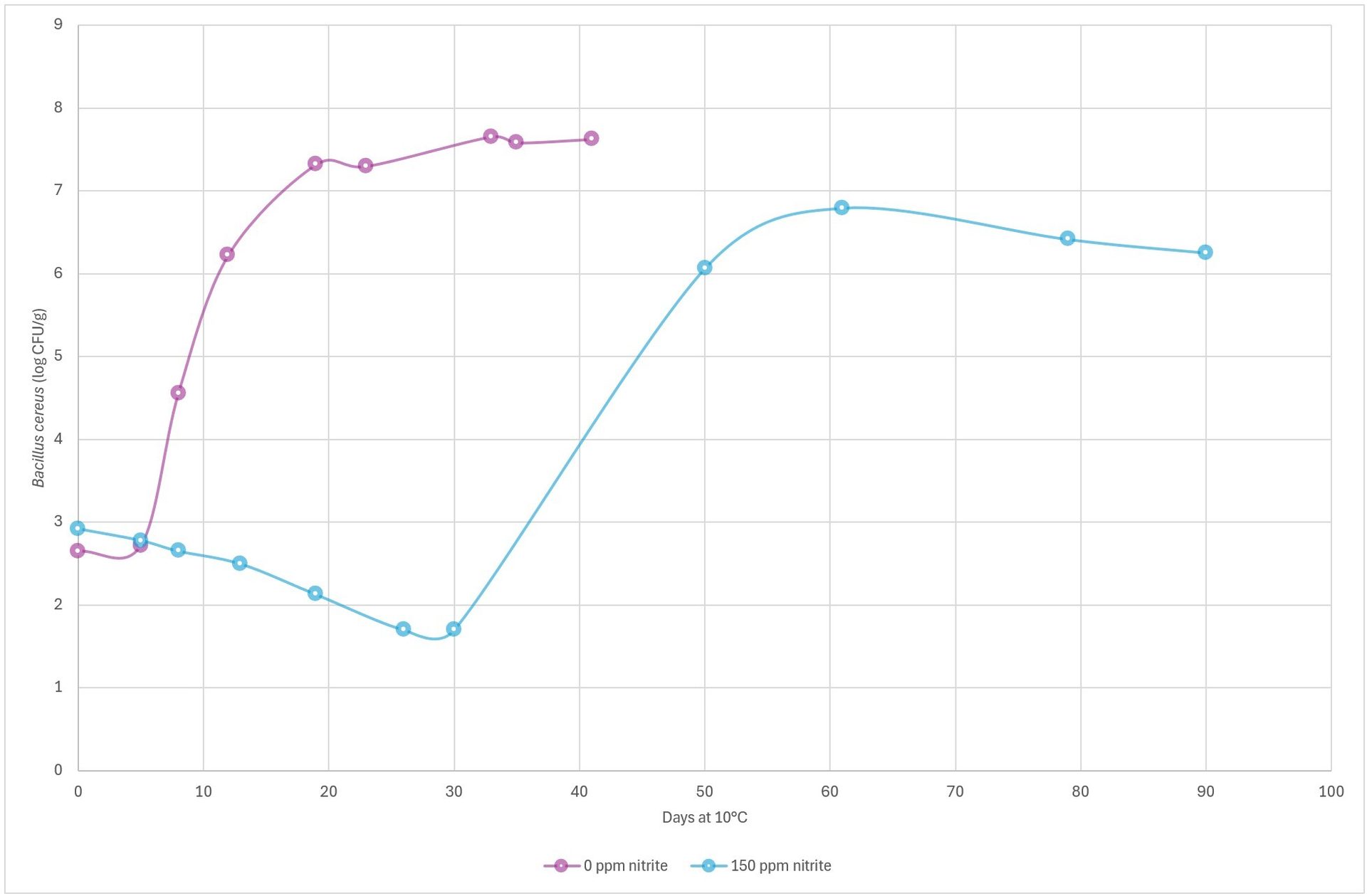

At 3.1 percent salt/water, pH 6.3, and 10 °C (50 °F), B. cereus grew 3 log units in modified atmosphere packaged meat sausages within approximately 11 days. The addition of 150 ppm of nitrite extended the time for 3 log growth to approximately 50 days (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5. Growth of B. cereus in processed meat at pH 6.3, with 3.1 percent salt/water, packaged in modified atmosphere (30 percent CO2/70 percent N2) and stored at 10 °C (50 °F), compared to products with 0 ppm of nitrite (purple) vs. 150 ppm of nitrite (blue) added (Credit: Danish Meat Research Institute)

These results show that the antimicrobial effect of nitrite against B. cereus is better at lower pH and higher salt concentrations. Thus, nitrite is a good hurdle in combination with other preserving agents. Reducing the level of nitrite will, depending on salt content and pH, require additional preservation (e.g., organic acids). If this is not an option (e.g., due to clean label requirements), then setting a shorter expiration date for the product will be required.

A model to predict the growth of B. cereus in processed meat stored at 5–10 °C (41–50 °F), packaged in vacuum or modified atmosphere (30 percent CO2/70 percent N2), will be made available at DMRI Predict by the end of 2026.

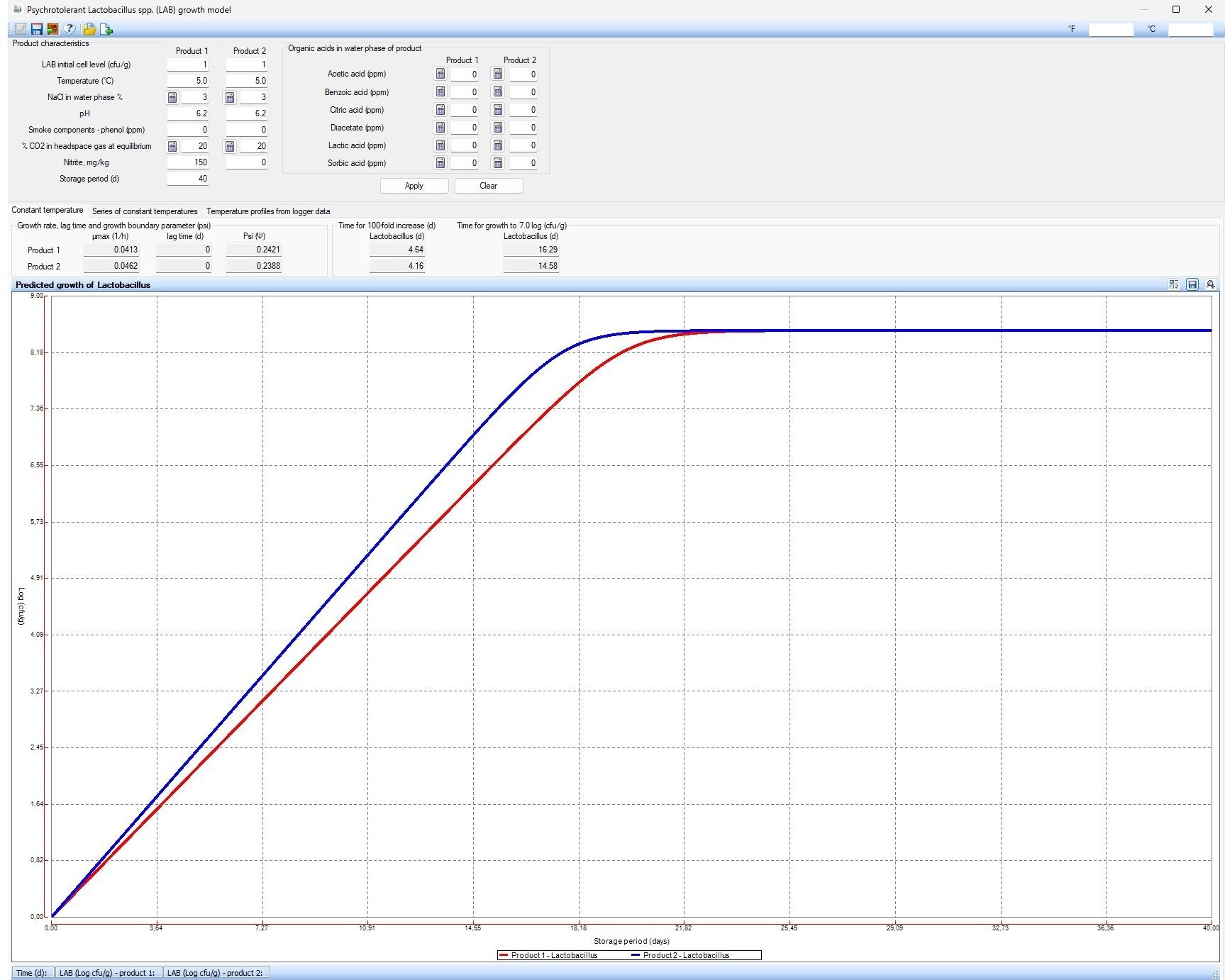

Nitrite and Lactic Acid Bacteria

The effect of nitrite on lactic acid bacteria (LAB), which are common meat spoilers, is more limited and varies depending on the specific spoiler. During the development of the model for Leuconostoc growth in modified atmosphere packaged deli meat, DMRI found that nitrite did not affect the growth, whereas the FSSP growth model10 shows that nitrite has a slight impact on the growth of Lactobacillus. As shown in Figure 6, the time to reach 7 log CFU/g (estimated level to cause spoilage) is 16 days with 150 ppm of nitrite added compared to 14.5 days when no nitrite is added.

FIGURE 6. Predicted growth of Lactobacillus in products with 0 ppm of nitrite added (blue line) vs. 150 ppm of nitrite added (red line) (Credit: Technical University of Denmark, "Food Spoilage and Safety Predictor")

“The call to reduce nitrite concentrations is not concerning in general, as it is possible to reduce nitrite in most meat products and still avoid growth of pathogens or spoilage organisms by adding organic acids and salt.”

Takeaway

To summarize, the addition of nitrite to processed meat products has profound, practical implications for sensory quality and consumer perception. The chemical reactions described above, especially those involving nitric oxide and myoglobin, are directly responsible for the distinct pink to red color that consumers expect in cured products like ham and sausages. This stable coloration, along with improved shelf life and safety, plays a significant role in how these products are visually evaluated and accepted.

Moreover, nitrite inhibits the development of undesirable off-flavors, maintaining the characteristic aroma and flavor that consumers associate with high-quality cured meats. Its antioxidative action helps preserve these qualities during storage and after cooking, suppressing both rancidity and warmed-over flavors. Certain aroma-active compounds, further enhanced by nitrite, also contribute positively to the distinctive flavor profile found in classic cured meats. Without nitrite, processed meats are likely to appear less appealing—often taking on a dull, grayish hue—and are more prone to rapid flavor deterioration. Thus, nitrite is indispensable not only for safety and shelf life, but also for supporting the sensory characteristics (color, aroma, and flavor) that define traditional processed meat products and meet consumer expectations.11,12

Nitrite plays a significant role in safeguarding processed meat against spoilage and growth of pathogens. Nitrite is very efficient in inhibiting spore germination and growth of Clostridium spp. and B. cereus when combined with salt. It is also efficient in inhibiting the growth of L. monocytogenes in combination with salt and other preservatives.

The call to reduce nitrite concentrations is not concerning in general, as it is possible to reduce nitrite in most meat products and still avoid growth of pathogens or spoilage organisms by adding organic acids and salt. Suitable combinations can be explored using the models at DMRI Predict. One exception is the survival and growth of certain heat-resistant Clostridium spores that could spoil canned meat, where a current data gap to document the effects of a nitrite reduction needs to be closed.

Acknowledgments

The work to develop and update DMRI Predict has been funded with financial support from the Danish Pig Levy Fund and the Danish Agency for Higher Education and Science.

References

- Sebranek, J.G. and J.B Fox. "A Review of Nitrite and Chloride Chemistry: Interactions and Implications for Cured Meats." Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 36, no. 11 (November 1985). https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.2740361122.

- Stoica, M. "Overview of Sodium Nitrite as a Multifunctional Meat-Curing Ingredient." Annals of the University Dunarea de Jos of Galati, Fascicle VI: Food Technology 43, no. 1 (2019): 155–167. https://doi.org/10.35219/foodtechnology.2019.1.12.

- Skibsted, L.H. "Nitric Oxide and Quality and Safety of Muscle Based Foods." Nitric Oxide 24, no. 4 (May 2011): 176–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.niox.2011.03.307.

- Melios, S., S. Grasso, D. Bolton, and E. Crofton. "Sensory Quality and Consumer Perception of Reduced/Free-From Nitrates/Nitrites Cured Meats." Current Opinion in Food Science 58 (August 2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cofs.2024.101183.

- Govari, M. and A. Pexara. "Nitrates and Nitrites in Meat Products." Journal of the Hellenic Veterinary Medical Society 66, no. 3 (2015): 127–140. https://doi.org/10.12681/jhvms.15856.

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). "Opinion on the Scientific Panel on Biological Hazards on the Request from the Commission Related to the Effects of Nitrites/Nitrates on the Microbiological Safety of Meat Products." The EFSA Journal 14 (November 2003): 1–31. https://efsa.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.2903/j.efsa.2004.14.

- EC Regulation No. 1333/2008 on Food Additives. December 16, 2008. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2008/1333/oj/eng.

- DMRI Predict. Danish Meat Research Institute. 2025. www.dmripredict.dk.

- Codex Alimentarius. "Code of Hygienic Practice for Processed Meat and Poultry Products." Vol. 10, Annex D. 1994.

- Technical University of Denmark (DTU). "Food Spoilage and Safety Predictor (FSSP)." Version 4.0. July 2014. http://fssp.food.dtu.dk/.

- Bekhit, A.E.-D., D.L. Hopkins, F.T. Fahri, and E.N. Ponnampalam. "Oxidative Processes in Muscle Systems and Fresh Meat: Sources, Markers, and Remedies." Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 12, no. 5 (September 2013): 565–597. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.12027.

- Møller, J.K.S. and L.H. Skibsted. "Mechanism of Nitrosylmyoglobin Autoxidation: Temperature and Oxygen Pressure Effects on the Two Consecutive Reactions." Chemistry 10, no. 9 (May 2004): 2291–2300. https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.200305368.

Anette Granly Koch, Ph.D. is the Scientific Manager for the Danish Meat Research Institute (DMRI) at the Danish Technological Institute (DTI).

Gudrun Margret Jónsdóttir, M.Sc. is a Consultant for the Danish Meat Research Institute (DMRI) at the Danish Technological Institute (DTI).

Marlene Schou Grønbeck, M.Sc. is Scientific Manager for the Danish Meat Research Institute (DMRI) at the Danish Technological Institute (DTI).

Gry Carl Terrell, M.Sc. is the Business Manager for the Danish Meat Research Institute (DMRI) at the Danish Technological Institute (DTI). She has an M.Sc. degree in food science and technology with emphasis on microbiology, food safety, and spoilage. Gry has diverse work experience from the food manufacturing and analytical industry in the U.S. and Denmark.