Current States of Food Safety Culture and Food Safety Management Systems in Food Establishments

In what ways is your brand either superior to or deficient from the behaviors revealed by your colleagues?

> COVER STORY

Video credit: 1shot Production/Creatas Video via Getty Images

SCROLL DOWN

Although the U.S. food supply is considered one of the safest in the world, there are an estimated 9.4 million occurrences of foodborne illness each year.1 Additionally, foodborne illness is estimated to cause more than 55,000 hospitalizations and more than 1,300 deaths each year in the U.S., burdening both individuals and the healthcare system.

By Mark S. Miklos, CP-FS, Advisory Partner, Active Food Safety; Elizabeth A. Nutt, M.P.H., Retail Food Safety Director, Association of Food and Drug Officials (AFDO); Steven Mandernach, J.D., Executive Director, AFDO; Susan W. Arendt, Ph.D., Professor, Iowa State University; and Yang Xu, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, University of Hawaii at Mānoa

Food producers, distributors, handlers, and vendors are primarily responsible for the safety of food. The role of industry professionals is significant to ensuring food safety. As personnel who control and supervise the daily operation of a food establishment, the responsibility of food safety lies with management. Management has traditionally relied on formal and technical interventions to control risk factors that can cause a foodborne illness outbreak. Recently, a parallel focus has emerged, one that emphasizes a more human-oriented method known as food safety culture.2

Food safety culture, which is part of an organization's larger culture, has been defined in several ways. Frank Yiannas, former FDA Deputy Commissioner for Food Policy and Response, notes in his book, Food Safety Culture: Creating a Behavior-Based Food Safety Management System, that it should not be viewed as a food safety program but rather "as how and what the employees in a company or organization think about food safety." To create this culture, "it is critical to have a systems thinking mindset," writes Yiannas.3 Others emphasize that "culture encompasses what employees believe," and that "culture is… shaped by what is measured and rewarded."4

Among the many definitions, however, the most frequently cited according to the recently published FDA study, Food Safety Culture Systematic Literature Review, is from Griffith, Livesay, and Clayton. They define food safety culture as, "The aggregation of the prevailing, relatively constant, learned, shared attitudes, values, and beliefs contributing to the hygiene behaviors used within a particular food handling environment."5

Purpose Statement

Researchers have suggested that an organization's food safety culture should incorporate its Food Safety Management System (FSMS). Although scholars and practitioners have proposed comprehensive frameworks and tools to understand and define food safety culture, few studies have been conducted in the U.S. to understand the state of food safety culture and FSMS currently practiced among the nation's leading brands.

The purpose of this study, as outlined in the Retail Food Safety Regulatory Association Collaborative Action Plan, was to understand the current state of food safety culture among U.S. food establishments, including restaurants, grocery stores, and convenience stores (C-stores). In addition, the study investigates the current state of FSMS, including the practice of Active Managerial Control (AMC). The findings provide a glimpse into best practices among the nation's leading brands and reveal opportunities to improve both food safety culture and FSMS. The potential may even exist for expanding the definitions of food safety culture itself.

Survey Methodology

In development and testing of an online survey, unintended bias was removed and pilot testing was conducted. Senior corporate or franchise food safety professionals (directors, vice presidents, and senior vice presidents) and owner/operators with responsibilities including food safety were invited to complete the Survey Monkey survey anonymously.

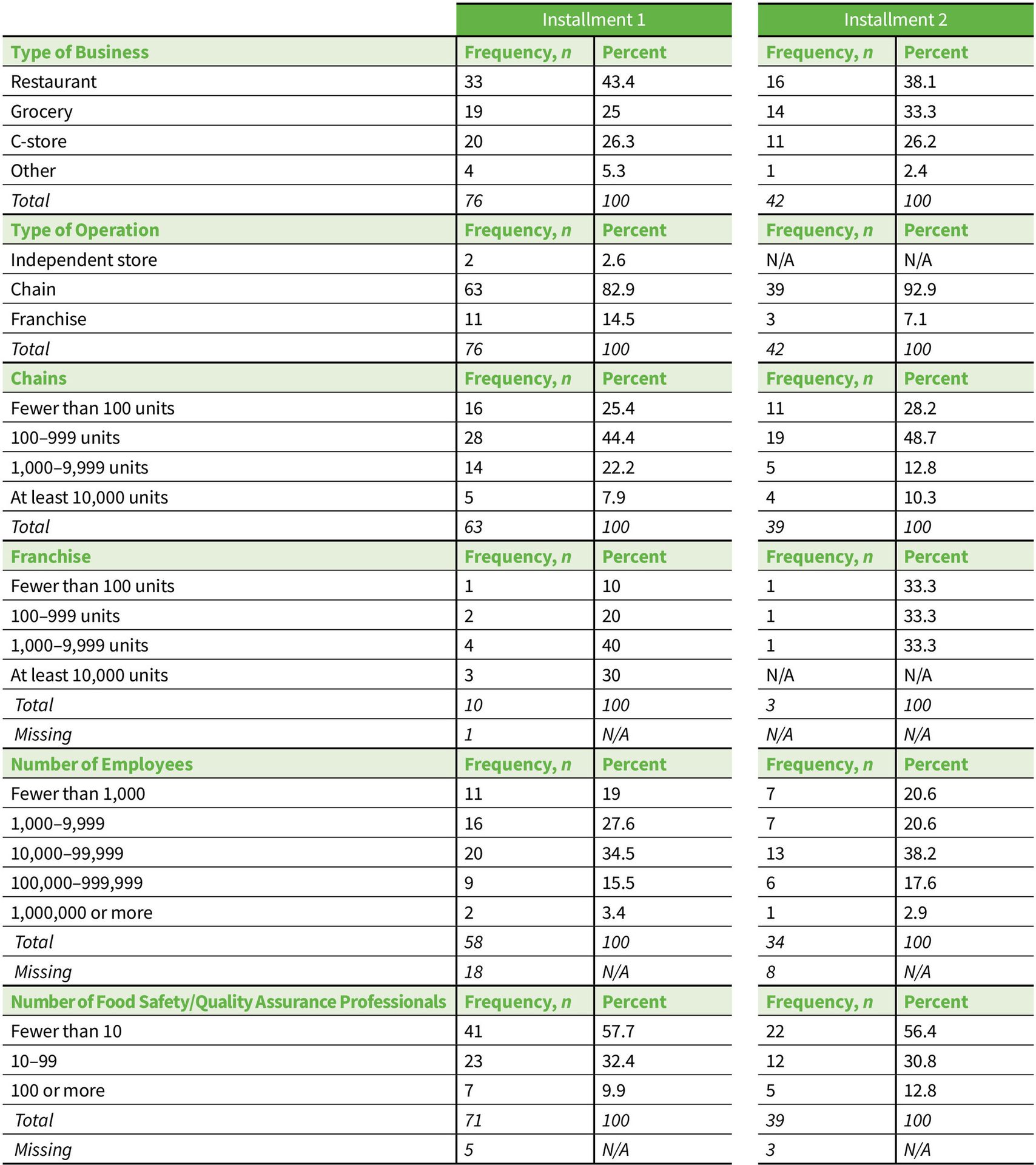

The survey was distributed in two installments. The first included questions about food safety culture and management practices, and the second featured questions on AMC and FSMS. Collaborations with industry associations (including the National Restaurant Association, the National Retail Federation Food Safety Task Force, the National Association of Convenience Stores, and Food Marketing Institute) resulted in an estimated sample size of 538, of which 209 were from restaurants, 168 from groceries, and 161 from C-stores. A total of 76 responses were collected in Installment 1 (33 restaurant, 19 grocery, 20 C-store, and four other) and 42 responses in Installment 2 (16 restaurant, 14 grocery, 11 C-store, and 1 other; see Table 1).

TABLE 1. Survey Demographics

The majority of respondents were from chain operations representing fewer than 1,000 units. However, in total, the dataset represented more than 337,000 units. A wide range of responses were reported for the number of full-time employees; an average of 37 percent reported having over 10,000 employees, while an average of 20 percent reported having fewer than 1,000 employees. Regarding the number of food safety or quality assurance professionals, the majority (58 percent) had fewer than 10, while 32 percent had 10–99, and 10 percent had 100 or more. Among these professionals, over 80 percent had bachelor's degrees or higher, while 70 percent also carried professional food safety credentials.

"In terms of who receives it, most organizations view food safety training as a brand standard, regardless of regulatory requirements."

Lessons Learned: What the Survey Revealed

Apart from the demographic information, 114 questions spanning 24 areas of inquiry were posed to determine what current restaurant, grocery, and C-store operators do to promote and sustain food safety culture and FSMS within their brands. Ten relevant examples are detailed below.

1. Food Safety Training

In terms of who receives it, most organizations view food safety training as a brand standard, regardless of regulatory requirements. Most respondents said that employees handling food (85 percent) and Persons in Charge (75 percent) received food safety training. Regarding training by industry segment, grocery had the highest percentage, reporting employees who handle food (88.2 percent) and all employees (52.9 percent) as receiving training. Restaurants had the highest percentage for Persons in Charge (PICs) being trained (78.1 percent).

The approaches used by companies for ANSI-accredited food handler training were mixed; about 46 percent indicated that it was required as a brand standard, regardless of regulatory requirements; 31 percent said they used in-house, brand-specific training instead; and 22 percent indicated they required it only as required by regulatory authority. When asked if the PIC or Manager in Charge (MIC) of food safety is present during every shift, 70 percent said this was so in every jurisdiction, 23 percent indicated only where required by regulatory authority, and 7 percent said they do not utilize PICs or MICs.

2. Management Practices: Employee Intervention and Role Modeling

As for management who notice staff not practicing safe food handling but do not speak up (Table 2), the majority said that it happens sometimes (33.3 percent). Slightly more than one-fifth (22.2 percent) indicated that it never happens. About 19 percent of the respondents indicated that it happens often, and 14.3 percent indicated that it happens occasionally. Another 11 percent of the participants did not have information regarding this issue (unknown).

TABLE 2. Management Notice Staff Not Practicing Safe Food Handling Without Speaking Up

With regard to managers' role modeling correct food safety behavior themselves (Table 3), most participants reported that the managers did it consistently but failed occasionally (49.2 percent). Another 27 percent of the respondents said managers tried to model correct food safety behavior but were inconsistent, and 15.9 percent indicated that managers always led by example.

TABLE 3. Manager Leads by Example in Terms of Practicing Safe Food Handling

3. Food Safety Audits

The vast majority of participants use third-party food safety audits (88.3 percent; Table 4). As for the kind of audits, most participants said the audit is a surprise visit. About one third (34.4 percent) reported the audit is a blend of surprise and announced, and only two participants said it was announced. The results of audits were used for making corrective action plans (96.7 percent), followed by improving the overall food safety system (93.4 percent), and using it for root cause analysis (75.4 percent). More than half indicated that the results were used as performance metrics (55.7 percent) and agenda topics for C-suite or owner meetings (54.1 percent).

As for consistency between audit programs and regulatory inspections, the majority (57 percent) of respondents viewed this as "somewhat consistent"; 28 percent of the respondents indicated that the result was "completely consistent," and 15 percent said that the result was "inconsistent." Among those who indicated that there were inconsistencies, all but one said that the audit identified more food safety risk factors than their regulatory inspections did.

TABLE 4. Third-Party Food Safety Audits

4. Supplier Audits

An alarming 43.3 percent of participants indicated that they do not conduct supplier audits (Table 5). Among those participants, three were from the restaurant industry, six were from the grocery stores, and four were from C-stores. Over half of the participants, however, reported that they do conduct supplier audits.

TABLE 5. Conduct Supplier Audits

5. Understanding of Food Safety Culture

The first installment of the current study assessed participants' understanding of food safety culture (Table 6). The majority of the participants who completed Installment 1 of the survey indicated that they are either responsible for driving food safety culture within the organization (34.7 percent), that they are well-versed in food safety culture (30.6 percent), or that they understand it well (25 percent). Only six participants (8.3 percent) said that they have limited understanding of food safety culture.

TABLE 6. Understanding of Food Safety Culture

6. Food Safety Management System

The current state of an organization's FSMS was self-reported as underdeveloped by 26 percent of the respondents, well-developed by 33 percent, and well-developed and documented by 41 percent. No respondents indicated that it was nonexistent. Interestingly, when asked about their understanding of food safety culture, 35 percent said they were responsible for driving it, 31 percent indicated they were well-versed, 25 percent said they understand it well, and 8 percent indicated a limited understanding. In other words, even though 91 percent indicated understanding and/or driving of food safety culture, 26 percent reported they had an underdeveloped FSMS; this appears to point to a disconnect whereby respondents were responsible but still evaluated their own FSMS as inadequate.

Respondents were also asked to describe how their establishments or brands comply with each of the six elements of an FSMS designed to achieve AMC (i.e., written policies and procedures, training, monitoring, corrective action, oversight, periodic reevaluation). Similarly, another question asked how food establishments implement each of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's (FDA's) recommended public health interventions for the control of foodborne illness risk.

Examples of Compliance with Six FSMS Elements

- Written policies and procedures: Incorporated into training guide, made available online, reviewed with all associates

- Training: Certifications required for managers and supervisors; digital, e-learning, and hands-on training used; communication with the training department on methods of delivery

- Monitoring: Use of logs and checklists, manager checks throughout the day, electronic systems, and third-party monitoring/auditing

- Corrective action: Follow-up on audits, coaching, completing proper and required documentation

- Management oversight: Managers conduct daily store walks; supervisors review temperature logs; supervisor, district, and regional managers make visits

- Periodic reevaluation: regular (quarterly/annual) and consistent reevaluation, utilization of third-party audit results

Examples of Public Health Interventions

- Demonstration of knowledge: Set goals and provide bonuses, require certification, perform training evaluation/knowledge checks

- Employee health controls: Provide training and orientation, have health policy in place, do daily health screens, use employee health reporting agreement, manager monitors

- Controlling hands as a vehicle of contamination: Provide supplies and tools, provide training, signage, standard operating procedures

- Time and temperature parameters for controlling pathogens: Provide training, time/temperature monitoring and recording, and HACCP controls including the process HACCP approach

- Consumer advisory: Post signage, use messaging, and train employees

Given that these questions were open-ended, response examples for each element were collected. It is interesting to note that responses regarding "demonstration of knowledge" appear minimal, and it is unclear why respondents did not provide interventions specific to "demonstration of knowledge." Results may be indicative of limited understanding of Food Code Section 2-102.11.

7. Food Safety Management Systems and Linkage with Food Safety Culture

The association, or link, between the current state of FSMS and food safety culture was further analyzed by using the Chi-Square analysis (Table 7). The Chi-Square (χ2) test, or Chi-Square test of independence, is a statistical method commonly used to evaluate the possible association or differences between two categorical variables.6 Categorical variables are groups or categories,7 such as the current state of FSMS in Table 7 (two categories: underdeveloped and well-developed).

An understanding of food safety culture (Table 6) was combined to form three categories:

- Limited understanding

- Well understood

- Responsible for driving it.

Similarly, the current state of FSMS was also combined to reflect FSMS as underdeveloped and well-developed. The results suggest that there were no associations between the understanding of food safety culture and the current state of FSMS. However, given the small sample size of this analysis (n = 22), it is reasonable to suggest that the result may be more indicative of a trend rather than statistical results. Given the results shown in Table 7 in terms of the number of counts for the responses, it appears that individuals who understand food safety culture well or who are responsible for driving it are associated with the current FSMS being well-developed.

TABLE 7. Associations between Current State of FSMS and Food Safety Culture/Relationship-Building

8. Explaining the Value of FSMS

When examining ways to explain the value of implementing an effective FSMS to the C-suite, the question was open-ended and asked the participants to illustrate by offering examples. Among those responses, six themes were identified. The most frequent theme mentioned by the respondents was "reporting" (37.5 percent), followed by "convey risks" (29.2 percent) and "convey benefits" (20.8 percent). The theme of Key Performance Indicators (KPI) and "not needed" appeared twice, respectively, in the responses (8.3 percent). The last theme, "incentive," was identified once. Examples of the themes, as well as the responses, are shown in Table 8.

TABLE 8. Ways to Explain the Value of Implementing an Effective Food Safety Management System to C-Suites

9. Intentional Relationship Building with Regulatory Authority

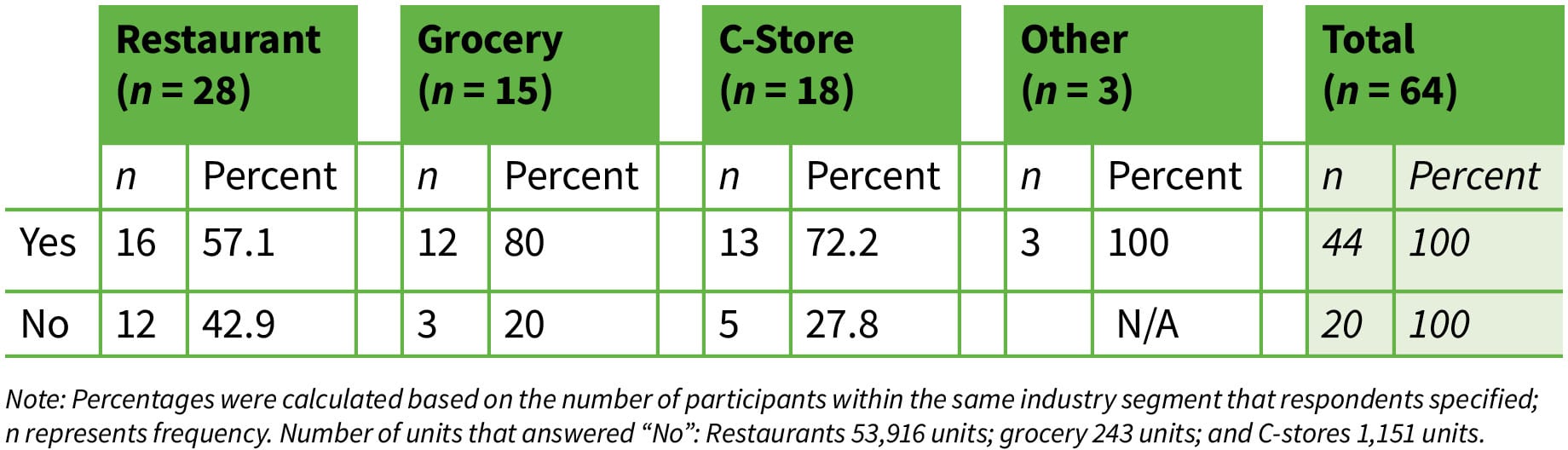

While the majority of respondents (69 percent) reported that they were engaged in intentional relationship-building efforts with their regulatory authority, 31 percent said their company was not engaged in such efforts (Table 9). This 31 percent represented more than 55,000 units (53,916 restaurants, 243 groceries, and 1,151 C-stores). Within the restaurant industry surveyed, about 43 percent of respondents said they did not engage in intentional relationship-building efforts. As for grocers and C-stores, the percentages dropped to 20 percent and 27.8 percent, respectively.

Chi-square analysis was performed to determine if those brands that made the effort to establish positive working relationships with the regulatory authority were more likely to have well-developed FSMS. Similarly, Chi-square analysis was also performed to determine whether the number of industry associations that respondents belonged to led to well-developed FSMS (Table 7).

No statistical significance was found between either the number of industry associations joined or the effort to establish positive working relationships with the regulatory authority and the current state of FSMS. However, there appeared to be a trend in both cases: Joining more industry associations (three or more) and/or building positive working relationships with the regulatory authority is associated with having a well-developed FSMS.

Since there appears to be a trend showing intentional relationship-building may be associated with having a well-developed FSMS, the 31 percent of respondents that do not engage in these efforts will want to reconsider this a priority.

TABLE 9. Engagement in Intentional Relationship-Building Efforts by Segments

10. Regulatory Authority Assistance

When asked if the regulatory authority helped to develop and implement an FSMS to achieve AMC (Table 10), 55 percent said yes and 45 percent said no. Examples of ways in which regulatory authorities helped included having discussions, using certificate programs that reward stores, serving together on advisory committees, and meeting at conferences.

TABLE 10. Regulatory Authority Help to Achieve AMC of Foodborne Illness Risk Factors

Opportunities

The survey's findings may prompt readers to consider in what ways their brand is either superior to or deficient from the behaviors revealed by their colleagues. Five ways to immediately improve a brand's food safety culture and FSMS are listed below.

1. Improve Management Practices in Areas of Role Modeling and Coaching

According to the results in Table 3, more than a quarter (27 percent) of the participants reported that managers try to role model proper food handling behaviors, yet make mistakes at the same frequency as their employees. Moreover, about half (49.2 percent) of the participants indicated that management occasionally fails to model the correct behavior.

As the leader whose behaviors will be followed and copied by employees in the establishment, the consistent and correct role modeling of proper food safety behavior is critical in ensuring food safety. Leadership models point to the importance of leaders modeling the way and exhibiting desired behaviors for employees to see.8 Modeling of correct food safety behavior ought to be viewed as part of the overall corporate culture. In addition, modeling correct food safety behavior should be an imperative of every food protection manager's job description and verified through performance metrics. Managers need to continuously participate in food safety retraining programs to enhance their own safe food handling behaviors.

2. Conduct Supplier Audits

Less than half of the respondents (43.3 percent; see Table 5) indicated that they do not conduct supplier audits. In addition, 12 percent said that they do not consider a supplier's food safety culture when deciding to do business with them. According to Fung et al.,9 all food distributors, handlers, and vendors are responsible for food safety. Food establishments should realize that safe food practices not only depend on their own operation, but also on the behaviors and practices of their suppliers. Supplier audits must, therefore, be implemented as a best practice.

3. Build Relationships with Regulatory Authorities

According to the number of counts presented in Table 7, there was a trend: Those participants who engage in intentional relationship-building are more likely to have an FSMS that is well-developed (n = 12). Industry food safety professionals should not only participate in conferences and meetings with regulators, but also take a more assertive approach and proactively engage with the regulatory authority at the local level. Become an ambassador for your brand and share what you are doing to control foodborne illness risk factors in your establishments. This is particularly important whenever new foods, processes, or methods are introduced in your establishments.

Another example of the value of working together as partners with a common purpose of ensuring food safety is illustrated when writing disaster preparedness plans for regulatory approval (e.g., water and power disruptions), as provided for in Food Code Section 8-404.11 (C).

4. Establish Top-Down Accountability for Food Safety

According to the results presented in Table 4, 45.9 percent of participants indicated that they do not share audit results with members of the C-suite as an agenda topic to be discussed in meetings. Furthermore, 19 out of 62 participants (30.6 percent) reported that they do not have shared accountability for food safety from senior leadership down to food handlers in their organization. As an important index to measure top-down accountability, participants were asked whether management's performance bonuses were tied to food safety metrics (e.g., regulatory inspection scores, third-party audit scores, and customer foodborne illness complaints). The "no" responses to those questions were 71 percent, 46 percent, and 86 percent, respectively. When the same three questions were asked in terms of whether store-level employees' performance bonuses were tied to food safety metrics, the percentages of "no" were even higher (88 percent, 76 percent, and 91 percent, respectively).

In a true culture of food safety, everyone, no matter their position, shares accountability for food safety outcomes. Depending on the current corporate culture, implementing a top-down model of accountability for food safety verified through performance measures and supported by reward and recognition programs could be a heavy lift for some establishments, but no FSMS can endure long without it.

5. Understand the Relationship between a Mature FSMS and Views on Food Safety Culture

Similarly, despite the statistical results presented in Table 7, the trend showed that those who indicated they understand food safety culture well or are responsible for driving it are also more likely to have a well-developed FSMS. This is also consistent with the view that FSMS is an integral part of a robust food safety culture. It is not so much a case that food safety culture precedes FSMS or that FSMS is the predicate to food safety culture, but rather that the two are symbiotic—they progress together. Therefore, companies should conduct gap analysis of both their FSMS and their food safety culture and adopt the best practices articulated in these survey findings.

"Those brands with food safety cultures that support intentional relationship-building with regulatory authorities showed a trend for having a well-developed and mature FSMS."

Summary

The current study of restaurant, grocery, and C-stores was proposed as a first step in convening key industry associations to learn best practices in food safety culture and FSMS, including AMC, among U.S. food establishments as set forth in the Retail Food Safety Regulatory Association Collaborative Action Plan. A structured survey distributed to senior food safety practitioners and thought leaders in the industry provided a glimpse into what the nation's leading brands are currently doing in these areas. The complete data set is rich, and opportunities were identified to build a more meaningful food safety culture and a more robust FSMS.

Novel understandings emerged as they relate to top-down, shared accountability for food safety within an organization, intentional relationship building with regulatory authorities, and indeed, the very relationship between a mature FSMS and food safety culture, among others. In the first case, a lack of shared accountability will doom any effort to implement real culture change. Likewise, no FSMS will long endure without the industry–regulatory relationships espoused by best-in-class operators, as reflected in the survey findings. Remember, those brands with food safety cultures that support intentional relationship-building with regulatory authorities showed a trend for having a well-developed and mature FSMS. An organization's top-down accountability for food safety and its willingness to proactively build relationships with regulatory authorities should be jointly considered when defining food safety culture.

It is worth asking again: In what ways is your brand either superior to or deficient from the behaviors revealed by your colleagues? Think of this article as a call to action, and work together to increase the number of food establishments with well-developed and implemented Food Safety Management Systems for controlling the risk factors associated with foodborne illness outbreaks!

Funding Acknowledgement Statement

This article was supported by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of a financial assistance award (FAIN) totaling $1,000,000, with 100 percent of this article funded by FDA/HHS. The contents are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement by, FDA/HHS or the U.S. government.

References

- Scallan, E., R. M. Hoekstra, F. J. Angulo, et al. "Foodborne Illness Acquired in the United States—Major Pathogens." Emerging Infectious Diseases 17, no. 1 (2011). https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1701.P11101.

- De Boeck, E., L. Jacxsens, M. Bollaerts, and P. Vlerick, P. "Food Safety Climate in Food Processing Organizations: Development and Validation of a Self-Assessment Tool." Trends in Food Science and Technology, 46, no. 2 (2015): 242–251.

- Yiannas, F. Food Safety Culture: Creating a Behavior-Based Food Safety Management System. New York, New York: Springer, 2009.

- Ades, G., K. Leith, and P. Leith. The Food Safety Puzzle. Elsevier, 2016.

- Griffith, C. J., K. M. Livesey, and D. A. Clayton. "Food Safety Culture: The Evolution of an Emerging Risk Factor?" British Food Journal 112, no. 4 (2010): 426–438.

- Franke, T. M., T. Ho, and C. A. Christie. "The Chi-Square Test: Often Used and More Often Misinterpreted." American Journal of Evaluation 33, no. 3 (2012): 448–458.

- Urdan, T. C. Statistics in Plain English. 3rd Edition. Routledge, 2010.

- , J. and B. Posner. The Leadership Challenge. Wiley, 2017.

- Fung, F., H. S. Wang, and S. Menon. "Food safety in the 21st century." Biomedical Journal 41, no. 2 (2018): 88–95.

Mark S. Miklos, CP-FS, is Advisory Partner at Active Food Safety.

Elizabeth A. Nutt, M.P.H., is Retail Food Safety Director for the Association of Food and Drug Officials.

Steven Mandernach, J.D., is Executive Director for the Association of Food and Drug Officials.

Susan W. Arendt, Ph.D., is Professor of Hospitality Management at Iowa State University.

Yang Xu, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor at the University of Hawaii at Mānoa.