SUPPLY CHAIN

By Roy Fenoff, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Department of Criminal Justice, The Military College of South Carolina (The Citadel); and Byung Lee, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice, Central Connecticut State University

Food Documents as Food Fraud Facilitators

Food fraud is accomplished in numerous ways, and document fraud may be one of the easiest ways for food fraudsters to operate undetected

Image credit: Antoniooo/E+ via Getty Images

SCROLL DOWN

Fraud, which is deception used for economic or personal gain, has been around since the beginning of human history. Although the technologies used to commit fraud have evolved over time to adapt to structural changes in society (e.g., fraud in person vs. fraud online), many fraudulent schemes have withstood the test of time. Human social behavior, the way we think, how we connect and relate to others, and how we are taught to trust people we do not know well are products of human nature and have remained persistent and predictable throughout the years. This predictability makes us, and the organizations we work for, susceptible to fraud.

However, fraud schemes are rarely successful without a person or thing making the fraudsters' actions unnoticeable or credible. Documents are one such category of thing that has made fraud easier to commit and more difficult to detect. Documents are pervasive throughout society, and we have been programmed to generally trust the authenticity of the documents presented to us. For example, when presented with an identification credential such as a driver's license or passport, the receiver rarely questions the document's validity. After all, the person presenting the identity document went through an identity verification process. Another example is when a certificate of analysis (COA) is presented to the customer by the supplier to demonstrate that the shipment received meets the agreed-upon specifications, the customer rarely questions the authenticity of the COA. The supplier has presumably been vetted, is likable, and appears trustworthy.

While reading this, you might be thinking, "Not me. I am intelligent, skeptical, and I'm confident I would be able to spot a fake document if one were presented to me." Are you sure? How would you determine the authenticity of the document presented to you? If you are receiving hundreds of documents each day, then how long would it take you to complete the authentication process for each document? Practically speaking, most people do not have time to investigate and verify the documents they encounter in their daily routines. Moreover, life would become an inefficient and unbearable experience if every person and organization were trying to independently verify most of the documents they received daily. So, for businesses and society to operate efficiently, we must grant a level of trust to the people and documents we encounter in both our personal and professional lives. Of course, fraudsters understand this reality very well and use it to their advantage. In this regard, documents are used to facilitate their illicit activities.

The food industry relies on a countless number of documents to keep food supply chains moving quickly and efficiently, to help ensure food safety, to satisfy legal and regulatory requirements, and to communicate product information to consumers. However, the food industry's reliance on these documents also provides opportunities for fraudsters to exploit food fraud countermeasures and to perpetuate food fraud events. This article explains what those documents are, how they facilitate food fraud, and why incorporating a review of food documents as part of your food fraud vulnerability assessment can go a long way in reducing the fraud opportunity.

Food Fraud Prevention is Challenging

Food fraud has been a part of human societies since antiquity. However, until recently, it was not a focal point for the food industry or regulators as the focus has traditionally been on the unintentional contamination of food products. As a result, food fraudsters did not need to expend a great deal of effort to carry out a food fraud event, and the risks of getting caught were negligible. Now that food companies are well aware of the food fraud risks, they are actively assessing their food fraud vulnerabilities and employing food fraud prevention countermeasures when deemed necessary.

Indeed, we have come a long way in understanding the risks associated with food fraud to the food industry and consumers. Food fraud is an intentional act where an individual or business deceives others using food, food products, or food packaging for economic gain. Food fraud takes a variety of forms, but the most common techniques used by food fraudsters are substitution, adulteration, counterfeiting, and mislabeling. Given that food fraud has become a focal point for the food industry and government regulators such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), and the China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA), the effort food fraudsters are required to expend to carry out a food fraud event has greatly increased. As a result, food fraudsters are innovating. They do this by making decisions based on their ability to imagine new ways to evade current security measures, execute them at speed, and avoid detection to keep the fraud going as long as possible. If they did not innovate, then we would not need to be constantly assessing our food fraud risks and vulnerabilities. In effect, we would have already won, and food fraud would have gone the way of rinderpest cattle disease.

Since food fraudsters have the first-move advantage and can rapidly innovate, the food industry has often found itself operating reactively (e.g., the European horsemeat in beef scandal). Therefore, prevention is the goal. We do not want to catch food fraud; we want to prevent it before it happens. However, food fraud prevention can be challenging because it requires businesses to imagine which food or food product the fraudsters will attack, how they will attack it, how they will evade current security measures, and how they will respond to future countermeasures.

“Structural changes in routine activity patterns of food producers, suppliers, workers, and consumers can impact food fraud by increasing or decreasing the opportunity for fraud.”

Food Fraud Prevention and Fraud Facilitators

Food fraud prevention is based on a group of crime theories that focus on crime events. In this regard, the place of crime matters and the role that immediate environmental circumstances play in making food fraud more or less likely to occur is important. Three theoretical perspectives that have been developed to understand crime events and explain food fraud are: Routine Activity Theory, Rational Choice, and Situational Crime Prevention. When combined, these perspectives capture the thought process of fraudsters: how they make the decision of when and where to commit food fraud, how they perceive a target to be suitable, and how guardians can prevent food fraud. Some readers may be familiar with Routine Activity Theory and Situational Crime Prevention, but they may not have been exposed to the concept of fraud facilitators and their role in food fraud. Before introducing the concept of fraud facilitators, a brief review of the three theories identified above will be helpful.

While exploring the relationship between humans and their environment, Cohen and Felson1 argued that crime can be understood by recognizing individuals' routine activity patterns. According to the Routine Activity Theory, three factors must be present for a crime to occur: a motivated offender, a suitable target, and the absence of a capable guardian. Of these three factors, guardianship may be the most important component in preventing a crime event. By disrupting the interaction between a motivated offender and a suitable target, a guardian can directly or indirectly prevent fraud from occurring.

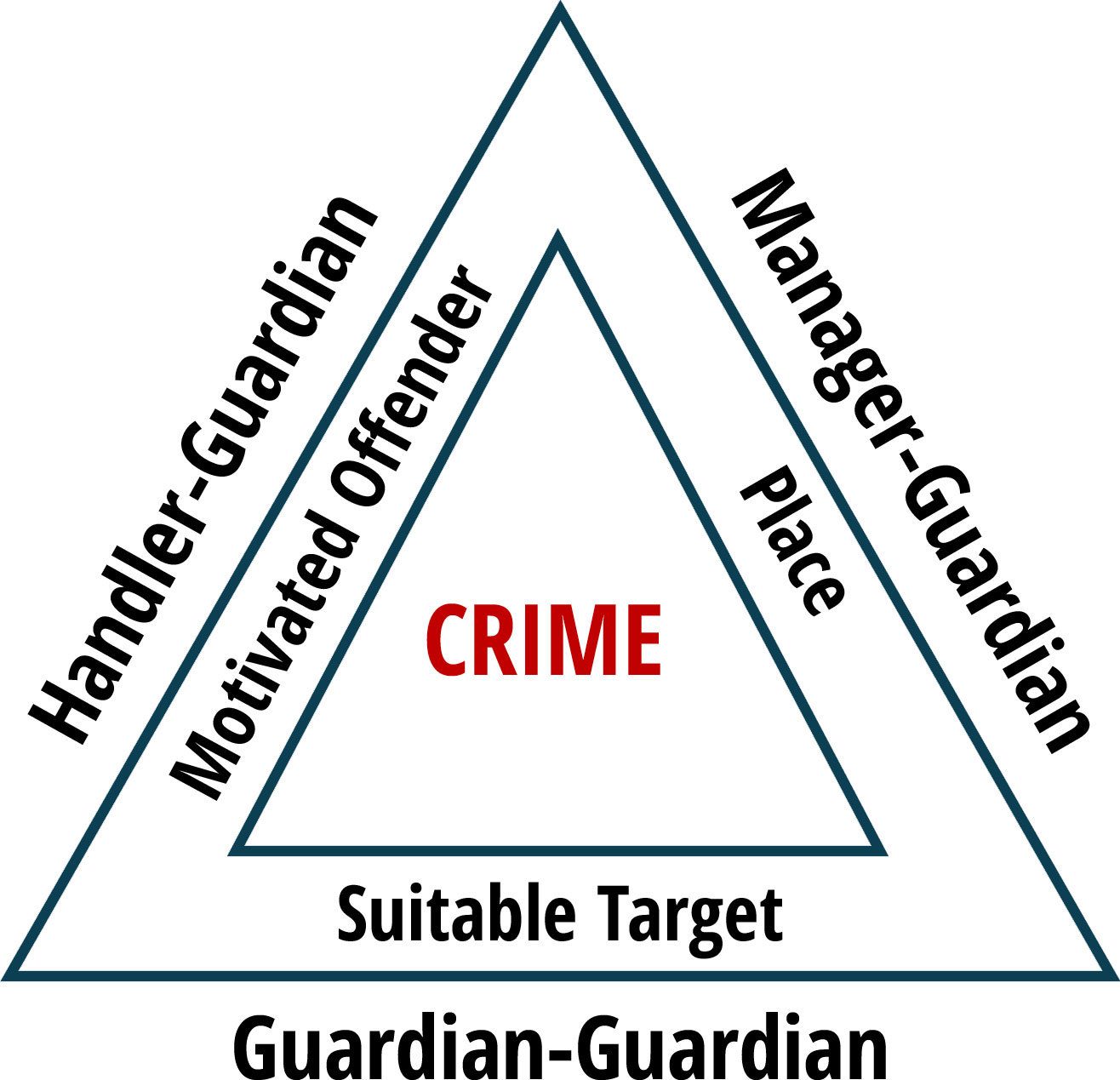

To better visualize and understand this interaction, John Eck2 proposed that the "crime triangle" should consist of two layers (Figure 1). The inner layer represents the three elements necessary for a crime to occur, and the outer layer represents the three types of guardians that may prevent a crime. According to Eck, the intervention of any one guardian can be sufficient to prevent a crime from taking place. Felson and Boba3 explained how the three forms of guardianship are interconnected in the sense that a crime is accomplished when a motivated offender moves away from handlers, toward a place without a manager, and toward a target without a guardian. When thinking about the food industry, the probability of these three elements converging in space and time is influenced by routine activity patterns of food producers, suppliers, workers, and consumers moving along the food supply chain. Structural changes in these patterns can impact food fraud by increasing or decreasing the opportunity for fraud.

While the Routine Activity Theory identifies the necessary elements for food fraud to occur, the Rational Choice perspective describes how fraudsters make decisions. The Rational Choice perspective asserts that food fraud results from calculated, reasoned choices using a cost-benefit analysis. Food fraud is more likely to occur when the expected gain exceeds the expected costs. Consequently, the decision to commit food fraud is a two-part process. First, individuals must be willing to commit the fraud, and then they must decide what type of food fraud they want to commit (e.g., counterfeiting, substitution, adulteration). These decisions are greatly influenced by the fraudsters' assessment of the immediate situation.

Situational Crime Prevention is the applied side of routine activity theory. The goal is to reduce fraud opportunities through the manipulation of the immediate environment to deal with specific forms of food fraud. Therefore, manipulating situational factors and altering the perceived benefits and costs of food fraud could change an offender's decision-making process. Unlike many generic approaches to crime prevention, which apply various techniques to a broad range of problems, Situational Crime Prevention focuses on a precise problem, in a specific place, under particular circumstances to make the target unattractive to criminals. Fraudsters make choices based on their assessment of potential opportunities. Therefore, understanding how fraudsters see events is important to preventing food fraud because almost all food fraud prevention strategies will involve changing the food fraudsters' perceptions of fraud opportunities.

Fraud facilitators help fraudsters commit and perpetuate food fraud. Three types of fraud facilitators are defined: physical, social, and chemical. Each type of facilitator helps fraudsters get around food fraud countermeasures. Physical facilitators (e.g., computers, documents, melamine used to mimic protein in milk) help fraudsters overcome prevention measures that increase risk or effort. Social facilitators encourage fraud by enhancing the rewards from the food fraud event, legitimating excuses to commit food fraud, or encouraging participation in food fraud, which often occurs with members of criminal networks. Chemical facilitators include substances like drugs and alcohol, which increase the fraudsters' ability to ignore risks or miscalculate the costs and benefits of their fraud scheme.

Documents as Food Fraud Facilitators

Documents are one of the primary food fraud facilitators and can be defined as any material that carries an explicit or implied message.5 Although documents are often associated with paper containing handwriting or computer-generated text, in its most broad interpretation, writing or printing on a wide range of substrates other than paper can also be considered documents. For example, graffiti left on the side of a building or a baseball containing the signature of a baseball player are both considered to be documents.

Document fraud is the use of an altered, counterfeit, or forged document, by an individual or group, for financial, political, or social purposes.6 Although the myriad of documents used in the food industry can be classified under the general document definition provided above, for food fraud prevention purposes, food documents will be defined as pieces of written, printed, or electronic matter that are used to provide evidence or information about food products, food ingredients, or food packaging. Some examples include documents related to imports and exports, bills of lading, certificates of analysis, credence attribute statements, invoices, sales receipts, as well as shipping, packaging, and product labels. Since documents are used to facilitate food fraud events,7 food document fraud can be specifically described as acts of deliberate counterfeiting, faking, altering, or forging of a food document to facilitate food crime.

Every industry is susceptible to document fraud, and the food industry is no exception. However, food document fraud can have more devastating consequences than document fraud in other industries due to its potential negative impact on public health.8 Moreover, the number and type of documents being used throughout the food supply chain, the speed at which they move, and the ease with which they are accepted as genuine, provide food fraudsters with numerous fraud opportunities with little risk of detection. In fact, most food fraud events are facilitated and perpetuated by fraudulent documents. As a result, it is important to understand the risks associated with the use of documents in the food supply chain so that countermeasures can be employed to reduce food document fraud, making it more difficult for food fraudsters to commit fraud.

Traditionally, food document fraud has not been systematically considered when food companies perform their annual Food Fraud Vulnerability Assessments (FFVA). Since research on food document fraud is relatively nonexistent, as an initial step to understanding the risks associated with the use of documents in the food supply chain, an ongoing survey is being conducted by researchers with the Food Fraud Prevention Academy (formally Michigan State University's Food Fraud Initiative). The Food Document Fraud Survey (FDFS) is being distributed among food industry professionals and expert groups to investigate their perception of food document fraud and to identify the documents that are most commonly used, altered, counterfeited, and forged in the food industry.

Results obtained from the FDFS indicate that documents are a latent vulnerability in the food supply system and most organizations are not prepared to identify and evaluate questioned documents. The study participants identified 35 different documents that they deal with on a regular basis. Of these, the five most reported were: COAs (56 percent), credence attribute statements or certifications (46 percent), bills of lading (22 percent), laboratory analysis test results (22 percent), and import and export documents (16 percent).

When asked about their experience with food document fraud, 86 percent of the participants reported being concerned about fraudulent documents entering the food supply chain in general and their organization, more specifically. While almost half of the study participants had encountered an altered or fake document (44 percent), the majority were unsure if they had encountered an altered or fake document (56 percent). This is an important finding because it shows that fraudulent documents are being encountered by food industry professionals, and it reveals the difficulty people experience in identifying questioned documents.

The fact is that the inability of food industry workers to identify and intercept fraudulent documents provides an opportunity that is being exploited by food fraudsters. When asked about their organization's capacity to identify and evaluate questioned documents, only 35 percent of the study participants reported having a process in place to identify questioned documents, and 28 percent reported having a document examiner or consultant on retainer. In other words, more than two-thirds of the study participants admitted that their organization did not have a process in place to identify questioned documents. Considering this, 90 percent of participants were interested in learning more about document fraud, and 72 percent were interested in starting a document fraud prevention program.

Takeaway

Food fraud is accomplished in numerous ways, and document fraud may be one of the easiest ways for food fraudsters to operate undetected. Considering the importance documents play in the food supply chain and the ease with which they can be altered, counterfeited, or forged, it is imperative that food organizations add a document fraud review to their prevention strategy project list. The sheer number and types of documents encountered by food industry workers on a daily basis can be overwhelming. Considering all of the different types of food documents that could be fraudulent, this adds up to a considerable amount of risk.

A good first step in document fraud prevention and response is understanding the types of documents commonly used within your organization and identifying those targeted by fraudsters. Begin by creating broad document categories for financial records, transportation records, and certification records. Next, identify and place each type of document used within your organization into one of these broad categories. Finally, review the different document types and rank them based on their level of risk for fraud.

This initial document screening process will offer some insight as to where your biggest document fraud risks are and where the document fraud is most likely occurring. Consider how the information obtained from your food document fraud analysis fits into and informs your food fraud vulnerability assessment. The important thing is to get started. Once you have a food document fraud assessment process in place, you can continue to refine it. Document your current state and needs, and create some food document fraud next steps.

References

- Cohen, L. E. and M. Felson. "Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach." American Sociological Review 44 (1979): 588–608.

- Eck, J. E. "Police problems: The complexity of problem theory, research, and evaluation." In Problem-Oriented Policing: From Innovation to Mainstream, Crime Preventions Studies, vol. 15. Monsey, New York: Criminal Justice Press, 2003.

- Felson, M. and R. Boba. Crime and Everyday Life. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, 2010.

- Clarke, R. V. and J. E. Eck. Crime analysis for problem solvers: In 60 small steps. Arizona State University Center for Problem-Oriented Policing. 2009. from https://popcenter.asu.edu/content/crime-analysis-problem-solvers-60-small-steps.

- Huber, R. A. and A. M. Headrick. Handwriting Identification: Facts and Fundamentals. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press, 1999.

- Fenoff, R."Forgery." In Encyclopedia of White-Collar and Corporate Crime, 2nd ed., vol. 6. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, 2013.

- Johnson, K. and R. Nickel. "China tells Canada to stop meat shipments over bogus documents." Reuters. June 25, 2019. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-canada-trade-china/china-haltscanadian-meat-shipments-over-bogus-documents-idUSKCN1TQ2UZ.

- Spink, J. and D. C. Moyer. "Defining the public health threat of food fraud." Journal of Food Science 75, no. 9 (2011): 57–63.

Roy Fenoff, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor in the Department of Criminal Justice at the Military College of South Carolina (The Citadel) and is a forensic handwriting and document examiner in private practice.

Byung Lee, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor in the Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Central Connecticut State University.